Outstanding Cuban painter Rocío García at this moment is immersed in her own creation and doesn’t want to be distracted by anything. Every day, in her studio/workshop in El Vedado, she talks with her characters and she especially enjoys the stories each one of them – together or separately – tells her from the canvas or the bristol board. Despite that, since she is “quite mystic,” she prefers to not give details “so the magic is not lost.” It is, then, more advisable to wait for her to surprise us with a new proposal that will surely make people talk.

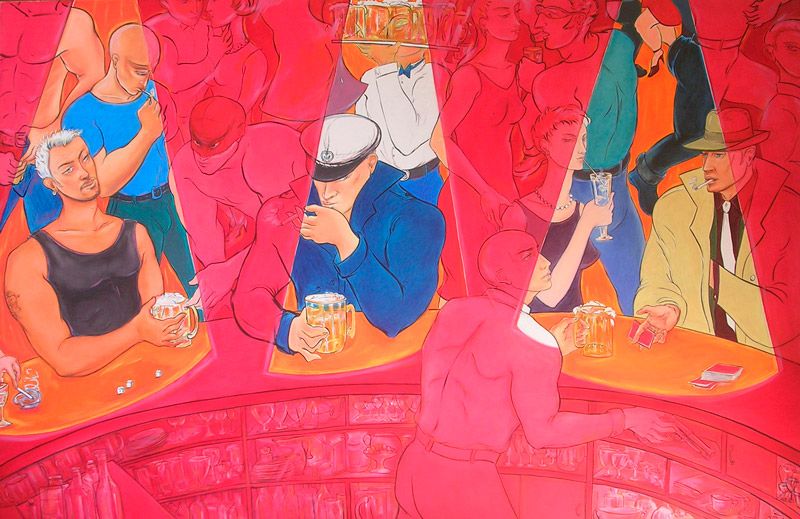

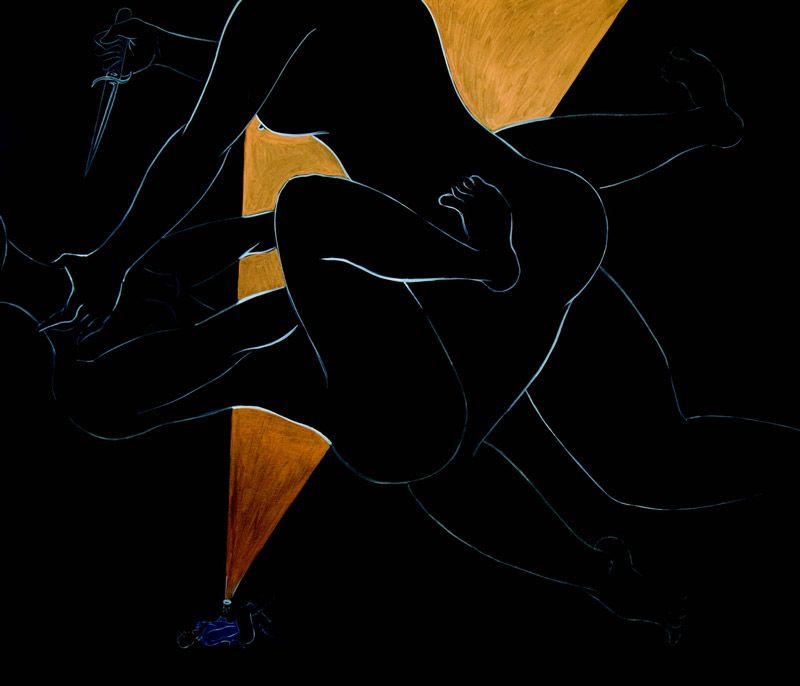

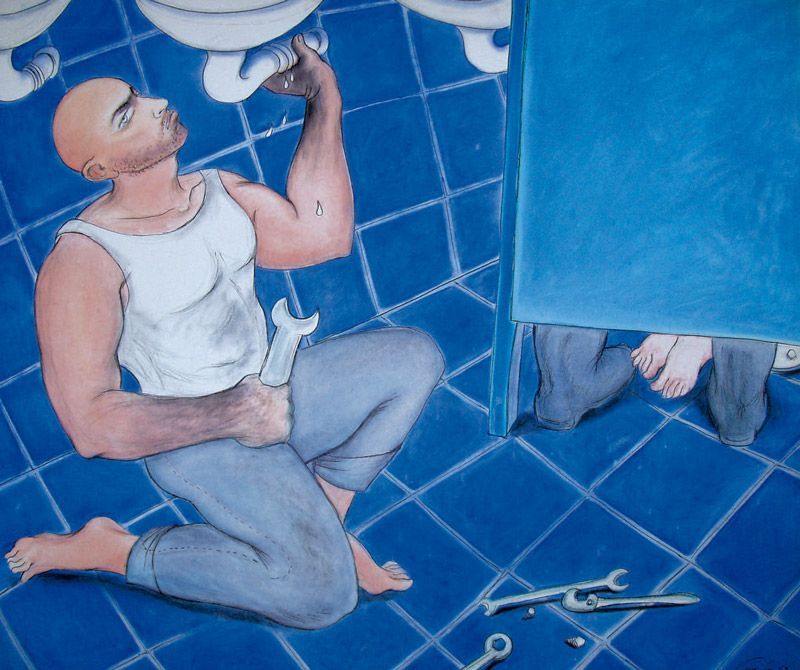

Rocío has been boxed in the homoerotic theme – and she recognizes it is an aspect that “touched, touches and will touch” her work – and a sign of this are her series: Peluquerías; Geishas; Hombres, machos, marineros; El domador y otros cuentos; Haikus; El thriller; Very, very light and very oscuro; El regreso de Jack el Castigador; and The misión, la más reciente.

If the work of this painter – who has a very clean drawing on which the composition of the structure of each work is based – is studied in detail, what strikes the eye is that she does not use effects or textures: her pictorial resources are extremely minimalist.

***

Rocío García was born in 1955 in the central Cuban province of Villa Clara and when she was barely four years old the family moved to the capital, where she studied. In 1975 she graduated from the San Alejandro Academy of Arts (in the specialty of painting) and she subsequently won a scholarship for a master’s in the Repin Academy of Fine Arts of Leningrad – today Saint Petersburg -, Russia. She graduated in 1983 from that prestigious center of higher studies.

With all the tools that both academies placed in her hands, she started structuring a pictorial discourse that has become sequential and very permeated by literature and cinema: “being a student of San Alejandro I not only submerged myself in the world of visual arts but also started seeing the fabulous films of Ingmar Bergman and Akira Kurosawa and they undoubtedly marked me; knowing other worlds allowed me to enhance my vision. I like to have a wide spectrum in the face of situations and I try to be objective, although it is impossible to avoid subjectivity. When I’m going to give an opinion I try to be extremely careful in order to not remain in the detail but rather go into the profound, the essences; I deal with my work in the same way,” she specifies.

She recognizes that the Russian academy – where she studied for seven intense years – was “very strict” and emphasized on composition, but she appreciates the knowledge acquired because it made her “clearly understand that one thing is technique and another thing is the creative part.” However, she considers that the best formation was the one she was given at an early stage by the Hermitage: “that marvelous museum was very near to the Academy and if on the one hand the professors are forming you and on the other you are seeing with your own eyes the work of Rubens, Rembrandt, Da Vinci, Picasso or Matisse, that entire world combines and you assimilate much more.”

Rocío’s work is not only known in Cuba but also in France, the United States, Switzerland, China, Spain and Japan, among other nations, where her series Geishas was very well received. With Geishas as a platform she discoursed on the feminine theme and later with Hombres, machos, marineros, she conscientiously spoke of the homoerotic theme, that is to say, of the love between two men: “I endorsed that it is a right and I dealt with it with beauty, but also with vehemence. That created an expectation and since I released it after the premiere of the film Strawberry and Chocolate, by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea (Titón), it was a favorable circumstance and the theme was accepted.”

Far from any boxing, what Rocío García’s work fundamentally questions is the concept of power, but not just on the sexual level but also on the social, psychological and political. Despite her thorny presentations, one perceives innumerable touches of humor: “it’s always there because I’m Cuban and its part of me: humor is an inherent part of our life and it’s a way of commenting, with certain amusement, in-depth presentations.”

Each one of the series she develops has intentionality not just in terms of content but also in the formal, and although her paintings are apparently independent, when they are joined – for example in an exhibition – spectators can perceive the movement of an idea that plays around and jumps from work to work.

Color is decisive to achieve such an effect: “my painting is not realist because I don’t use color so that it looks like photography but rather what predominates is the suggestion. Due to the chromatic relationship a certain dramatic charge is felt or a sensation that can be gentle, peaceful, aggressive or a sense of unease.”

Another important part of Rocío’s work is focused on her pedagogic work; and the thing is that this woman, who knows how much time individual creation absorbs, has devoted 20 years to teaching: “the relationship with the students is very beautiful because the teacher has the responsibility of giving, but they, at the same time, make you think based on questions and very complicated questionings. Pedagogues have to make an extra effort that forces them to not be inside the four walls of their studio/workshop. When I see that some of my students at San Alejandro start being successful and playing a protagonist part in contemporary art, I feel that there’s a little bit of me in each one of them. It sincerely makes me very happy.”

The codes of pop art, as artistic movement, and the influence of the comics are some of the supports that hold up the work of Rocío, a creator who bets on difference, singularity, knowing that the themes she deals with come from the reality that surrounds her, the Cuban reality, but at the same time they are universal topics: “human beings have more or less similar conflicts in any part of the world. Un policía con Alzheimer (from the series Very, very light… and very oscuro) can be Cuban but also from another country because there are military officers in the entire world; the power-erotic relations exist since the Greeks and a bit further back because ever since the times of caves human beings have been struggling for power,” she conclusively underlines.

LOCALIZATION:

www.rociogarcia.com

Studio: Calle 17 no.1016, apto 2E, esquina 12, El Vedado, Havana

Tel: 78334856, cell: 52812707