In 2017, the university student Yanay Aguirre Calerín was involved in an argument with a taxi driver in Havana. After receiving racist comments, she was forced to get out of the vehicle.

In Cuba, according to the 2012 Census data based on self-identified skin color, Whites represent 64.3% of the total population, Blacks represent 9.3%, and mulattoes 26.6%. Consistent with this data, the young woman who was discriminated against for being Black belongs to a minority. However, what her story reveals is not a minor issue.

Racism is expressed like a catalogue of prejudices, but more so it is a pattern of power that accumulates differences to systemically organize, distribute, and justify advantages and disadvantages. It unfolds through individual and institutional actions, while also defining the access to opportunities within the social structure.

The media debate around Cuba offers plenty of remarks about racism. On the one hand, it assures that only “reminiscences” of the scourge survive. On the other hand, it acknowledges that Cuban power structures practice State-sponsored racism. In contrast, an analytical look finds both improvements and problems in this field.

The Revolutionary Experience

In January 1959, the newspaper Revolución published the text, “Not Blacks…citizens!” in which Black people explained the meaning of what they considered to be a new life. In March 1959, two of Fidel Castro’s speeches broke existing segregation against Blacks to access public spaces, such as beaches.

The initial great measures of the Revolution—which included agrarian reform, rent reduction, scholarship plans, and job creation—equally benefitted Whites and Blacks.

As Ana Cairo said, “it became a moral and political postulate that no self-defined Cuban revolutionary could say or do something that could be perceived as racist,”[1] a major barrier to the spread of racial prejudices.

Walterio Carbonell identified a cultural profile of the contribution of Blacks and mestizos to the 1959 triumph: the “Afro-Cuban” cults undermined the cultural legitimacy of Catholicism, and the social order it organized, and diversified the scale of social values.[2]

After 1959, photography, cinema, theater, historical research, painting, publications, institutional work, sociocultural research, music, and literature reflect a repertoire of great quality and wide circulation that reworked the Black image as part of an effort to dignify historically marginalized subjects.

Its vanguard includes: Suite yoruba (1964) by Ramiro Guerra; Palenque y mambisa (1976) by the National Folklore Ensemble; or La última cena (1977) by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea (with collaborations by Manuel Moreno Fraginals and Rogelio Martínez Furé).[3]

Today, data show a different panorama to apparently “defining” ideas about racial inequality in the country.

The Census collects indicators that demonstrate contrasting distributions amongst Blacks and Whites: in some, Blacks have advantages, in others, both have similar proportions, and in others, the differences favor Whites. But, in a good number of cases, these differences are discrete.

Amongst university graduates, Blacks have larger representation (12.1%) than Whites (11.5%). There are more Blacks with master’s degrees than Whites—though this is not true for doctorate degrees. Houses built after 1982 are, in proportion, majority mulatto owned. Among Whites who are leaders, 88.8% are in the state sector, but among Blacks who are leaders in the state sector, 90.7%.

The percentage of White and Black professionals, scientists, and intellectuals is identical (15.6%). At the level of social perception, there is criticism that Blacks are majority “musicians and athletes,” though music and sports are sources of national pride.

There are differences, though not significant ones, with respect to the color of skin in the availability of services within the home, such as cooking or accessing a bathroom or shower, or in the possession of refrigerators, washing machines, or rice cookers.

On the basis of its indicators—which leave out, for example, a comparison of income in convertible currency—the official Census study concludes that the existing differentials between Whites, Blacks, and Mulattoes cannot “concretely confirm that this problem [racism and racial discrimination] is quantitatively present in a critical form in today’s Cuban society.”[4]

At other levels, education, health, and social protection systems have maintained the same universal character for the past six decades. The Labor Code (2013) expressly prohibits discrimination based on skin color. The new Constitution (2019) still prohibits it, and a National Program against Racial Discrimination has been approved.

This provides evidence to the thesis that the revolutionary period contains the best performance against racial discrimination in national history. Likewise, other examples point to truly relevant problems regarding racial issues in the country.

Problems Around the Racism Debate

Esteban Morales has made an inventory of issues concerning racism in today’s Cuba, among them the “lack of acceptance around its existence, insufficient public debate, absence of the subject in school curricula and mass media, limited presence in academic research, and the use of the issue as an instrument of internal political subversion.”

The researcher also points out conceptual errors when approaching the subject. In my opinion, three of these points are: presenting racism as a “vestige,” arguments that reject terms like “Afro-Cuban,” and the promotion of an uncritical vision of miscegenation.

Labeling racism as a vestige affirms that the present contributes to eradicating it, not reproducing it. That idea understands racism as a cultural issue—an aggregate of ideas and prejudices. It is, but that is not its only dimension. Limiting it in this way prevents one from appreciating how one’s material base upgrades the competition for power, opportunities, and resources.

That approach denies results from the social sciences that demonstrate the existence of a structural, social, and cultural heritage that is simultaneously “rebuilt in moments of crisis, in which competitive spaces appear.”[5]

Miscegenation is presented as the denial of all inequality originating from “race.” Ironically, that notion celebrates a nation without racial differences, but the 2012 Census reveals larger disadvantages precisely for mestizos (mulattoes).

Alberto Abreu questions this uncritical vision of miscegenation because it does not offer answers to dispute the “kidnapping” of “autonomy and cultural differences of black subjects and their gestures of counter memory, interpellation, and resistance to hegemonic culture.” It is, according to Abreu, the repertoire that has allowed it to “survive for centuries.”

The official Cuban language assures that the term Afro-descendent “is alien to our reality.” It is a statement that contains several conflicts.

Fernando Ortiz, a core reference of Cuban miscegenation, used the expression Afro-Cuban to dignify historically discriminated sources in Cuban culture. Collectives that use the term today do so to examine their experiences “using an approach that analyzes race, gender, class, sexual orientation, ability, religion, and geographic location,” all as part of an interrelated whole.

The Census criteria ignores both positions. Since it is reproduced by official bodies—as is the case in the 2016 report to the UN Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD)—it implies restrictions on the expression of identity and the imposition of the format of possible political participation based on discrimination.

The Double Dimension: Racism as Cultural and Structural

Racism is both cultural and structural in nature. It exploits the inequality of color, which is reinforced with others such as class and gender. It generates material poverty and cultural devaluation, social hostility, and malicious treatment. Such issues are not the sole consequence of skin color or class structure, but both are reinforced.

Declaring that racism exists, but that it is only “cultural”—without a structural component—reveals a poor theoretical understanding anchored in a politically interested use that ignores the mechanisms that reproduce racism. In contemporary Cuba, racism continues to produce differentiating class uses.

Around 2010, various investigations found that the Black and mestizo population had the worst houses, received less remittances, depended more on their personal effort and scarce resources to gain complementary income, had less access to emerging sectors; and in tourism, were mostly located in “inside” jobs not directly linked to the client.[6]

Taking into account the proportion of Blacks and mestizos in the population, these investigations coincide in that these groups had a lower presence (what is known as “under-representation”) in the tourism sector and within corporations; they constituted a small minority of the private agricultural sector (2%), and that of cooperatives (5%); they were at a disadvantage to receive remittances[7] and were underrepresented as heads of state-owned companies.[8]

A decade later, further investigations have arrived at similar conclusions. Specific research done on Black and mestizo groups finds that they experience income inequality in convertible currency, have fewer bank accounts and savings, travel less, have less access to internet, remittances, and another citizenship—including the travel advantages that come with it—and are rarely amongst those that own the most lucrative private businesses.

Other investigations confirm how structural dimensions coexist with cultural profile discriminations, such as stereotypes about Blacks and mestizos, which result in negative consequences for their labor and economic participation.[9] They observe that Black and mestizo women are the majority in informal employment areas such as street vending, elderly care, restroom and house cleaning, and informal business.

There is no information on the profile of the prison population, but it appears to be majority Blacks and mestizos, and there is evidence of racial profiling within police criteria for identifying possible offenders of the law.

CERD has shown concern over structural issues related to race in Cuba. In addition, it has deplored the lack of information on the direct application of the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination in Cuban courts and has pointed out deficiencies with respect to the investigation of complaints about racial discrimination, as well as cases of wrongdoing, police treatment of Black and mestizo people, and against anti-racist activists.

During his last term as head of the country, Fidel Castro reiterated the problems of racism at a national level and celebrated practices to improve disadvantaged sectors, a process known as the “Battle of Ideas.”[10] Both Raul Castro and Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, two of Cuba’s top leaders today, are also seen criticizing the consequences of racism in their statements.

Despite the evidence, there are tendencies to relativize, at both a social and official level, the structural dimension of racism in Cuba, the inequality it generates, and the systematic nature of its pattern of unfair distribution of opportunities and resources.

Paths to Follow

Solutions to racial inequalities must encompass elements such as cultural justice, law, distributive policies, and be able to define which paths can contribute to such solutions.

Schools can contribute to revaluing discriminated identities, promoting cultural change, undermining racial stereotypes, and promoting an acceptance of differences. Curricula should include subjects about General African History and its current processes, as well as the history of Cuban Blacks.

Racial discrimination is punishable in Cuba, but its procedural channels have not been effective: an official report in 2017 cited a single act of crime against the Right to Equality. The approval of a specific law on the subject and the provision of more resources for the protection of rights is a decisive step in the road ahead.

As Mayra Espina has argued, social policy must pay attention to disadvantaged groups, specifically to their intersection of class and “race.” It should include care services for children, the elderly, and the sick; free educational support services to improve school performance, preferential and advantageous subsidies or loans that support continued studies, as well as the construction of popular housing.[11]

Promoting is also caring. Affirmative action policies that redistribute opportunities and offer material and training support to sustain economic activities need to be established.

It is crucial to recognize the legitimacy of anti-racist activism in civil society. Organizations not recognized by the State—including those not considered dissident—face serious problems when it comes to legal registration and social performance. Greater participation, horizontal dialogue, and coordination between civil society and the State on the subject are pertinent.

Ethnicity, color, and anti-racism

Cuba is a nation with multi-ethnic origins that became a single racialized national ethnic group. Current genetic research demonstrates the miscegenation of the Cuban ethnos. However, the word “black” has certain specificities and different consequences than “white” throughout peoples’ social existence. There is a history to words and their uses. Anti-Black racism is a central component of the Cuban national formation.

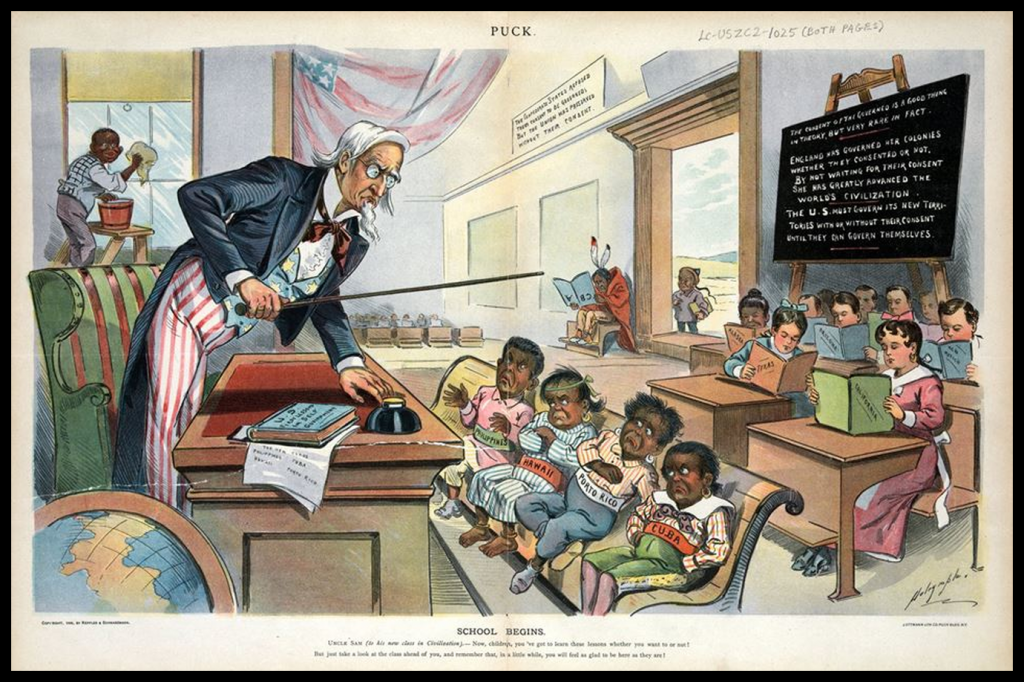

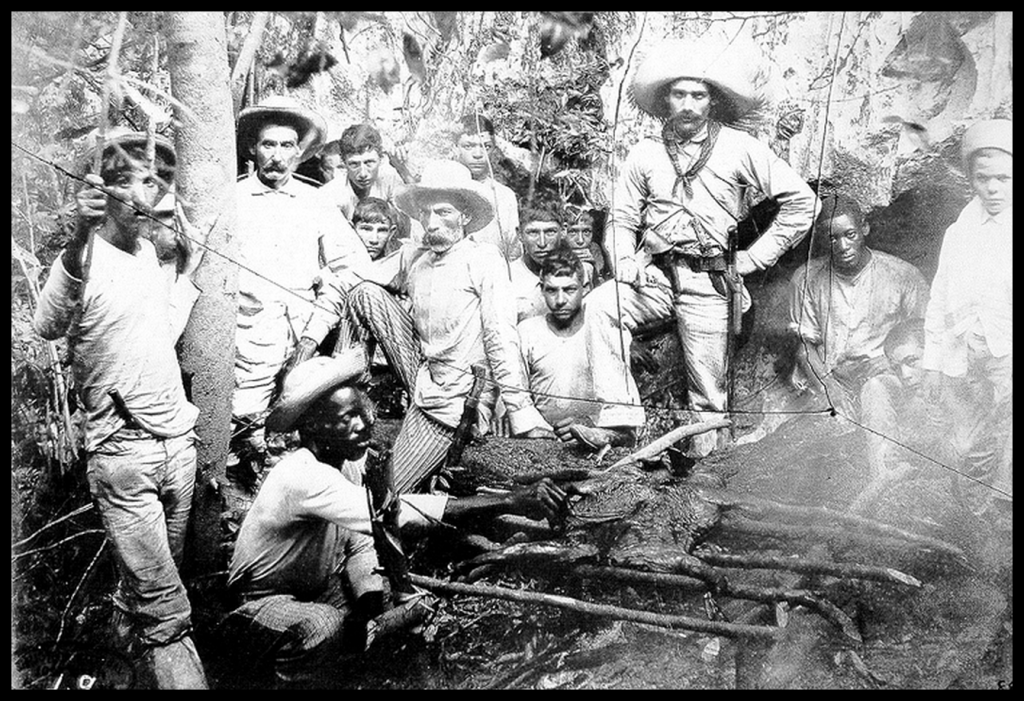

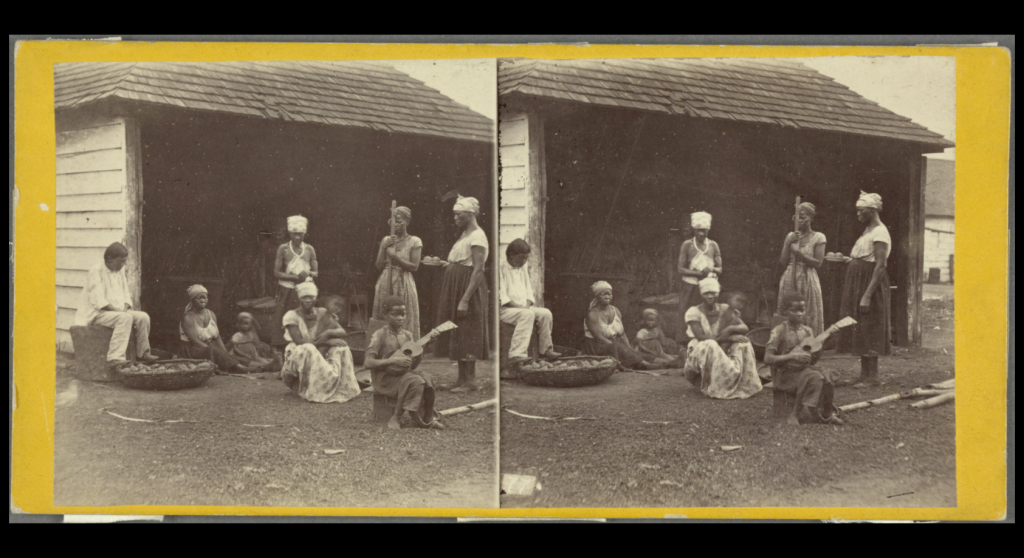

About a million Africans came to Cuba during the 19th century. Under the monstrous regime of slavery, the island became the world’s leading producer of sugar and the second Latin American country with the largest population of enslaved peoples, after Brazil. Each concurrent village/ethnic group in the slave process was fixed in certain social places, a fact that today marks the uni-ethnic nation that emerged from such foundations.

Words also have their impact. The color of skin is “the first element that Cubans use to form images of the other.”[12] It is not uncommon: the amount of melanin is the most obvious indicator of biological differences between people.[13]

Popular language has developed a vast set of representative words and phrases that refer to the color of skin. To refer to Blacks there is “negro-azul,” “negro color teléfono,” “negro coco timba,” “negro cabeza de puntilla,” or “negro.” For Whites there is “blanco,” “rubio,” “blanco orillero,” or “blanco lechoso.”[14] It is similar with other groups, such as mulattoes.

According to Jesús Guanche Pérez, all these terms may have, “depending on the context, an emotional or derogatory connotation,” but there is a consensus that the intensity of the presence of melanin is a factor of social differentiation. It is another way of saying that races do not exist, but there is racism.

In a history founded on slavery, race behaved as “a category of difference, as an engine of stratification and inequality, and as a key variable in the processes of national formation.”[15] The available evidence on inequality and skin color shows modes of reproduction of anti-Black racism in Cuba today.

In that context, limiting oneself to the idea of equal opportunities is problematic. It is more reasonable to defend the equality of results. With it, it is not about leveling down, but about closing inequality gaps and overcoming discriminatory ideas and practices that reproduce injustices.

Only in this way could there be a definitive change to the situation behind the Cuban saying, “in a White fishery, the Black man carries the nets.”

Julio César Guanche Zaldívar is a jurist, historian, and Ph.D. in social sciences. He was a professor at the University of Havana for a decade. He has taught classes, courses, seminars and conferences at universities in a dozen countries. Among them he has been visiting scholar and visiting professor at Harvard University (USA), Northwestern University (USA), Max Planck Institute for European Legal History (Frankfurt, Germany). He has directed several national publications and editorials in Cuba. He worked for several years at the House of the International Festival of New Latin American Cinema. He has published several books, as well as forewords and chapters in more than 20 volumes.

Notes:

[1] Cairo Ballester, Ana (2015): “La problemática racial en la cultura de la Revolución”. In Denia García Ronda (Ed.): Presencia negra en la cultura cubana. Havana: Sensemayá Editions, p.449

[2] Towards the end of the 1960s, Cuban religions of African ancestry were associated with criminality and certain counterrevolutionary behaviors. Guerra, Lilian (2014) “Raza, negrismo, y prostitutas rehabilitadas: revolucionarios inconformes y disidencia involuntaria en la Revolución”, América sin nombre, No. 19, 126–139

[3] Cairo, Ana (2015): Cited Work.

[4] Center for the Study of Population and Development. El Color de la Piel según el Censo de Población y Viviendas (de 2012), 2016, p. 62

[5] Rodríguez Ruiz, Pablo; Carrazana Fuentes, Lázara; García Dally, Ana J. (2011): Las relaciones raciales en Cuba. Estudios contemporáneos. Havana: Fernando Ortiz Foundation, p. 48

[6] Rodríguez Ruiz, Pablo, work cited (it is a compilation of different investigations and diverse authors). See also Rodríguez Ruiz, Pablo (2011): Los marginales de las alturas del mirador. Un estudio de caso. Havana: Fernando Ortiz Foundation.

[7] Refers to the fact that on that date, 83.5% of immigrants were White, and the remittances sent by them were proportionally higher, both in number of recipients (mostly their relatives), and in amount.

[8] Morales, Esteban (2010). La problemática racial en Cuba. Algunos de sus desafíos, Havana: Editorial José Martí, p. 129

[9] Pérez Álvarez, María Magdalena (1996): “Los prejuicios raciales: sus mecanismos de reproducción”. En Temas (no. 7, July-September), pp.44–50 and Pañellas Álvarez, Daybel; Cabrera Ruiz, Isaac Irán (Eds.) (2020): Dinámicas subjetivas en la Cuba de hoy: ALFEPSI Editorial

[10] (2006): Cien horas con Fidel, conversaciones con Ignacio Ramonet, 3rd edition. Havana: Publications Office of the Council of State, pp.258 et seq.

[11] Espina, Mayra (2015): “Desigualdades en la Cuba actual. Causas y remedios”. In Denia García Ronda (Ed.): Presencia negra en la cultura cubana. Havana: Sensemayá Editions, p.486

[12] Idem, p. 480

[13] Guanche Pérez, Jesús (1996): Etnicidad y racialidad en la Cuba actual. In Temas (no. 7, July-September), pp.51–57.

[14] Idem

[15] Alejandro de la Fuente y George Reid Andrews (2018): Estudios afrolatinoamericanos: una introducción. Buenos Aires, Massachusetts: CLACSO/:Afro Latin American Researcher Institute, Harvard University, p.11

*This text was originally published by Cuba Study Group.