Cubans born in the last 20 years are unlikely to associate their country’s physical landscape with a cow; not so with its cultural landscape. The tradition brought by the Spanish and that developed in the 20th century, “from Canadian cows and bulls to the world-record setting Ubre Blanca and the little cow Pijirigua, from Pedro Luis Ferrer’s famous guaracha,” implanted in the Cuban imagination a certain “obsession with eating a good steak or drinking a cup of milk with coffee at breakfast.”1

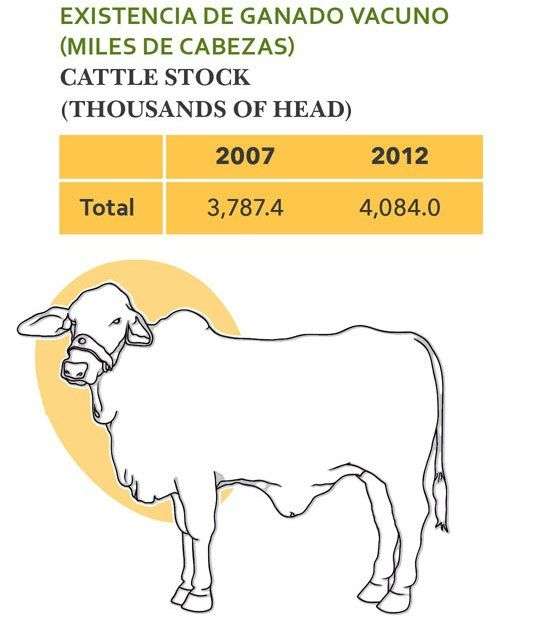

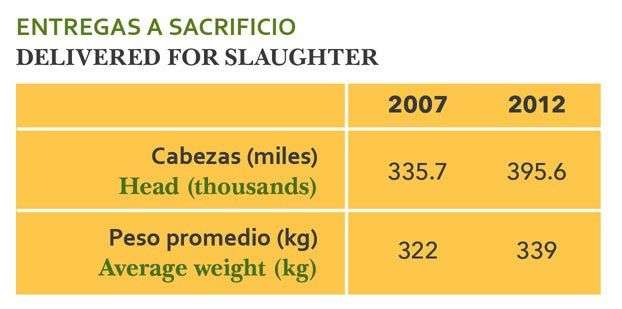

In 1980, the country produced 303,000 tons of beef, but in 1992, only 152,000. Cattle-raising, which crowned the Cuban economy in colonial times—before it was displaced by sugar cane—and which grew notably after 1959, collapsed after the disappearance of the USSR. The necessary supplies stopped coming. Feed had to be made self-sustaining through the use of grasses, proteinaceous trees, sugar cane, and a non-protein source of nitrogen. The industry never has returned to its former level.2

The cattle sector is also strategic: it closes agricultural cycles in general, ensuring their equilibrium.

In the first semester of 2012, total cattle production shrunk by 4.9 percent compared to the first quarter of the previous year. Beef also decreased, while milk showed a slight increase.

The supply is much diminished, and the official prices for beef and cow’s milk are very far from accessible for a large part of the population. On the black market, prices are lower, but in those channels of illegal trade, cheap beef can turn out to be expensive.

Article 240 of the Penal Code punishes the “illegal slaughter of cattle and the sale of their meat,” with prison turns of four to 10 years for those convicted of slaughter; three to eight for those who sell, transport or market the meat, and for the crime of receiving the product, a person who knowingly buys illegal meat can be sentenced from three months to one year in prison, fined 100 to 300 quotas, or both. In all cases, the authorities can confiscate any goods they deem appropriate.

In a speech on July 26, 2007, President Raúl Castro said it was a top priority to “produce more milk to ensure what is needed by our children first of all—we are talking about a food that is fundamentally for children, and for the sick; that cannot be played with, either…. We have to erase that age of 7 thing from our minds. We’ve been saying up until the age of 7 for the last 50 years. We have to produce milk so that whoever wants to can drink a glass of milk, and there is land to produce it.”

The new economic policy contained in the Economic and Social Guidelines resulting from the Communist Party’s 6th Congress leaves room for important reforms that have not been implemented yet in this productive sector of Cuban agriculture. Many hope for swiftness and perseverance, a rectification of old policies and bold openings that will make it possible to revive milk and meat production. It might be on the way. Meanwhile, we Cubans continue to nourish our yearning for beef.

1 Reinaldo Funes Monzote: “Cultura ganadera en la historia de Cuba. Una aproximación,” in Catauro, Year 13, No. 25, Havana, 2012.

2 Rena Pérez: “La ganadería cubana en transición”, in Catauro, ibid.

Measures suggested based on the new economic policy in Cuba

- Consolidation of a supply market and means of production.

- Diversification of the forms of production.

- Producer’s ability to make decisions throughout the production/commercialization/consumption cycle.

- Availability of financing and technical assistance for those who are starting out in the production process.

- Options to freely hire labor.1

1 Armando Nova González: “Impacto de los Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social en la producción nacional de alimentos,” in Economía cubana, ensayos para una reestructuración necesaria, Various authors, 2013.

Doing the math…

Cuban economist Armando Nova has made an interesting calculation. The State pays producers 2.5 pesos per liter (0.10 CUC) plus 0.02 CUC. The total is then 0.12 CUC per liter. At the same time, the cost of importing a ton of powdered milk is $3,914.0 in U.S. dollars (March 2012), in the port of Havana, including price, insurance, and transport. At the same time, a bag of milk (1 kg) produces 10 liters of liquid milk, which means that the price paid to the international producer for a liter of milk is $0.39 U.S. dollars. Therefore, the national producer receives only 30 percent (one-third!) of what is paid for the imported product.1

1 Idem.

How much does milk cost?

Consumers who go to the “shopping” (stores in CUC), find a 1-kg package at 5.75 CUC. If, instead, they go to the black market in Havana, they will find it at 75 to 90 Cuban pesos per kg (3.00-3.60 CUC), depending on demand. It is powdered milk, generally “diverted” (stolen) from state allocations for “social consumption,” the “ration” for children up to the age of 7, and special “diets” for medical patients. Some producers also sell surplus non-pasteurized liquid milk door-to-door in cities. This offer does not abound in Havana, but it can be found at 20 pesos per 1.5 liter container.

Eating a steak…in Havana

In CUC markets, one kilogram (about 2.2 pounds) of meat is very expensive for the average person’s wallet:

- Secondary grade meat: 6.50 CUC

- Steak cut: 9.00 CUC

- Filet: 16.50 CUC

And on the black market? It tends to be found for 5.00 CUC. However… be careful with the law! And there are no hygiene guarantees.

In a restaurant?

State

- El Palenque: 3.50 CUC

- La Ferminia: 5.00 CUC

- La Bodeguita del Medio: 16.00 CUC

Private

- El Cantonés (Barrio Chino): 5.00 CUC

- La Casa: 12.00 CUC

- Bom Apetite: 15.00 CUC