The Manhattan Chess Club that night was visited by one of its most illustrious parishioners. He is sitting in a corner, following with an attentive, incisive look the movements of a nearby chessboard. He smiles.

It is March 7, 1942.

Everyone there knows what the smiles of he who is observing mean. Everyone there knows him and admires him. The players, keeping an eye on his presence, avoid looking at him out of the corner of their eyes. Knowing they are being assessed by Capablanca makes anyone bite their nails.

During a pause, the Cuban champion talks with several of those present. He talks with Sidney Kenton about a possible quick chess tournament. A sudden heat consumes his body. His face reddens. A fatal whistle explodes in his ears.

“Help me take off my coat,” he is able to say before collapsing. After a rapid medical checkup, an ambulance takes him to Mount Sinai Hospital. There will be no salvation.

A cerebral hemorrhage caused by a galloping hypertension led to the death of the most genial of the chess players of his time. He was greater, undoubtedly, in the history of his country.

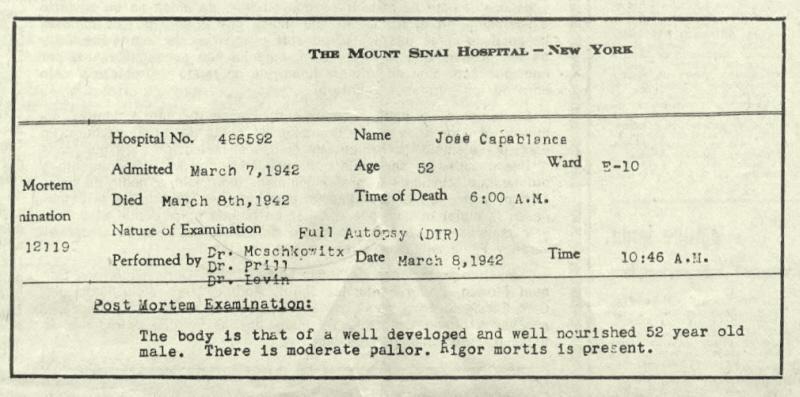

José Raúl Capablanca y Graupera stopped breathing in the early morning hours of March 8. The New York Times set the hour of his death at 5:30 a.m. The hospital’s report registered it at 6:00 a.m.

He was 53 years and 109 days old, although the autopsy report says he was 52.

In January 1941, at the same hospital, Emanuel Lasker passed away. Before this, Capablanca had won the world crown from him in 1921. Six years after he would lose it to Russian Alexander Alekhine, who never wanted to give him a return match. The Cuban took that frustration to his grave.

However, in his particular confrontations he shined over the son of Moscow. He won against him nine times, for seven defeats and 33 draws.

Capablanca accumulated a total of 600 official games, with 315 wins and barely 38 defeats. He won 22 of the 37 important tournaments in which he participated and won his first Cuban title when he was just 13 years old.

Some called him the human machine; others the Mozart of chess.

Between February 1916 and March 1924 he played 63 top-level games without losing a single one. This record included the match for the world championship against Lasker.

Alekhine, placing sincerity before spite, would say when the Cuban died: “Never before was there nor will there be a genius like him.”

Until his remains were transferred to Cuba, Capablanca’s body remained in the Cooke Funeral Parlor, on 117 West 72nd Street, New York. The island’s ambassador to the United States, Aurelio F. Concheso, traveled from Washington for the procedures. The remains of the chess player were also accompanied by an older brother and his widow, former Russian Princess Olga Chagodalf.

The funeral delegation arrived in Havana 75 years ago, on March 14, 1942. According to the daily Información, the ship that returned Capablanca to his homeland put in in the port of Havana at around 3:00 p.m.

Fulgencio Batista, then constitutional president, was personally in charge of organizing the ceremony held in the National Capitol building. The cortege left from there to Colón Cemetery.

Thousands of people gathered in Havana’s cemetery to bid farewell to Cuba’s idol. A painful silence received the coffin, covered in flowers.

Following Capablanca’s wish, his tomb is guarded by a majestic marble king sculpted by Florencio Gelabert. His greatest moment, however, is his own legacy, the major landmarks of a career that today still surprises the world.