At a very young age, Reynerio Tamayo invented his own world: instead of going out to play, he preferred to stay home and imitate the cartoons that he copied from children’s magazines; perhaps that is why his work today is unmistakably marked by graphic humor.

No family influence was involved in his inclination for the arts; however, he enrolled early on in the Elementary School of the Arts, in the special municipality of Isla de la Juventud, and then continued his studies at the Cuba’s National School of the Arts (ENA) and University of the Arts (ISA). From his student days, he holds fond memories of his teachers Antonio Vidal, who taught him how to paint with oils; Consuelo Castañeda; José Bedia; and Flavio Garciandía, all of whom contributed to the consolidation of his training and who gave him the essential tools for starting out in the difficult and complex world of art.

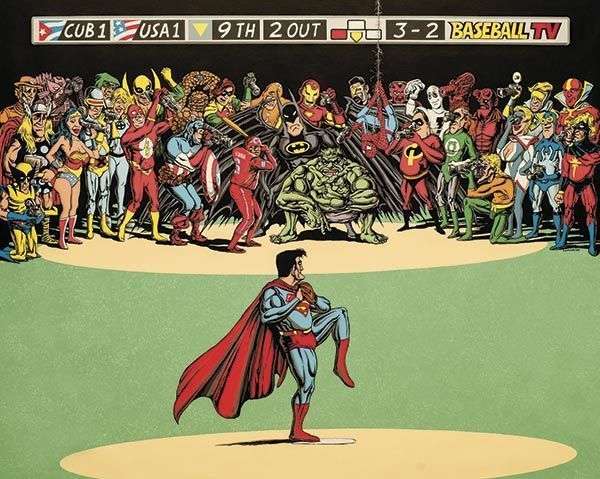

Humor is a recurrent theme in Tamayo’s work. At times refined, at others more caustic, or even hurtful, it can reflect the most authentic Cuban way of joking, something the artist noted in an exclusive interview with OnCuba: “It has been very intuitive. I approached humor in an empirical way. I haven’t conceptualized the very moment when it happened; it might have something to do with my earliest work: comics and cartoon stories. When you do comic strips, you begin by inventing characters, making them grotesque, deforming them, and exaggerating the drawing. That enabled me to do caricatures of my family and friends, and in doing that, you begin to somehow connect in that evolution.”

Tamayo views humor as a life philosophy, and uses it “as a bridge for communication,” because he is interested in interrelating with others, being provocative and being as direct as possible. Afterward, he says, “people can read whatever they want into my work, but I think that I am a maker of ideas, and that is why I’m not worried about having a bunch of different styles or trying to be like several other painters at the same time. There are artists who have a hallmark—I respect and admire that—but in my case, I’m not worried about it. I use style or technique in function of an idea; I make a mixture, or an ajiaco, but the interesting part is expressing, telling, and sharing certain ideas.”

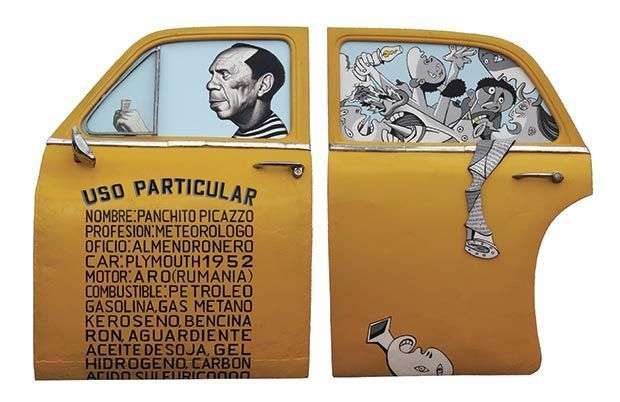

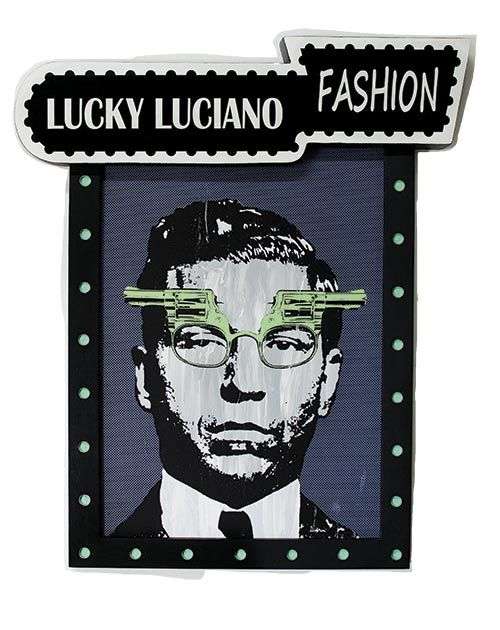

Throughout his intense career, he has addressed matters that range from criticism of violence, wars, abuse, power and exclusion to pondering humanity’s destiny, and those concerns “become themes. In my work, there are aspects, such as the history of gangsters in Havana, and what I do is use those characters as a pretext in my work. In the end, I’m talking about what I want, not the gangsters. Likewise, I’ve realized that the creative process is much better when it’s organized into series.”

In 2001, he won the First Erotic Art Salon Award, and even though that type of art is not exactly typical of his work, right now he is deeply involved in a project that recreates Japanese erotic engravings to a certain extent. He also enjoys making posters, a specialty that he became interested in through the work of the maestro Alfredo Rostgaard. He has created designs for music albums and books, noting that “illustrations for a book are as important as a cartoon, or graphic humor, or Picasso’s Guernica; anything that is a creative act and that says something new is the essence, the key,” he emphasizes.

While in recent times he has frequently used the formats of collage and silk screening, he considers himself to be a “typical easel painter.” He sketches, and when facing the blank canvas, has a defined idea.

Appropriating icons of universal art also has been a resource but always for talking about the present, the now, and one of his main sources of inspiration has been Havana, “a female city, very sensual, which has a lot to offer, but at the same time has been endowed with a large dose of surrealism. When I lived in Spain, I had to wring my brain to produce an idea, but here, you get up, go over to the balcony, and have all kinds of ideas right in front of you. You just have to capture them, metabolize them in the creative process, and reflect them in your painting.”

Tamayo dreams on, just as he did when he was a child, and now he is doing so with an upcoming installation that will be a shout from the present to the future: “Today, war happens over black gold, or oil, but it has been said that in the coming centuries it will be over blue gold, or water.”

And that is what art should be for, sounding an alert, placing burning issues in perspective, casting off bonds, understanding ourselves, learning about ourselves, and above all, communicating with each other.