I remember a news item that caught my eye a few years ago. In the press there was talk of a critical situation with swine production in one of the country’s provinces. The problem, it was said, was that the slaughter capacity was less than the production of standing swine. Thus producers were forced to extend the feeding of the animals for a longer time than was advisable, which caused losses and not only harmed producers, but also the entire production chain.

However, that news item was encouraging for me, it meant that production was such that the “industrial” profit capacities [1] in that province had fallen short. There are not many times that something like this happens in our country. It confirmed the wisdom of a successful productive development program implemented by the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI) to encourage the production of such an important protein, which combined the strengths of the state organization responsible for promoting swine production and those of the non-state sector. This program was also based on agreements (contracts) in which the state party delivered pre-fattening (small swine between 10 and 12 kg) at a specified price and part of the feed to non-state producers, and the latter delivered, months later, a number of animals ready for slaughter.

That program apparently worked so well that the so-called “national mammal” became almost affordable for everyone, even in the so-called supply and demand markets, where its prices ranged from 25 to 30 pesos per pound of loin, leg and shoulder and about 15 pesos a pound of ribs. What a time when there was always pork on the stand!

*Caption:

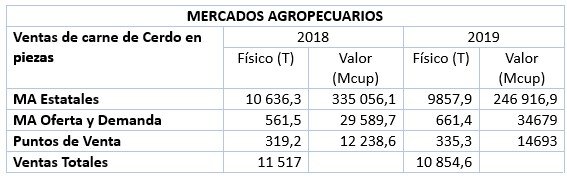

TOTAL SUPPLY: PORK (MT)

NATIONAL PRODUCTION

IMPORT

Today the presence of pork on the stands is sporadic and its price (officially capped) is well above those times when the pound of bone-in leg at 25 CUP seemed an exaggerated price. Unfortunately, I do not know why the National Statistics Office no longer publishes the informal market price bulletin, where the prices of agricultural products appeared. This was a magnificent instrument to better understand the evolution of this factor and the supply-demand relationship of different products.

It is true that very special circumstances have occurred that have triggered demand for the product, most associated with two factors: increasing financial difficulties in acquiring food and other products necessary for the production of pork (largely aggravated by the Trump administration) and the current COVID 19 pandemic that has increased demand for all food products. This situation is combined with a weak and unstable supply of other products such as chicken, hotdogs, and other sausages, as well as the perennial absence of fish, which has generated “uncommon” behaviors among consumers, a breeding ground for that figure that has accompanied us for so long: the resellers.

Let’s keep track of the national mammal. Let’s go to public data. [2]

The existence of swine experienced systematic increases from 2013 to 2018, the last year with available data. For 2018, inventories were 2,289,100 heads, of which 820,600 belonged to state-owned companies (35%). Then it can be said that the non-state sector is responsible for most of the stock of swine.

It should also be borne in mind that the Cuban state subsidizes part of the production by subsidizing the necessary food prices that it delivers to swine producing enterprises.

The delivery of swine for slaughter behaved as shown in the following table:

*Caption:

Delivery for slaughter (standing)

Total standing price (MT)

State (MT)

Non-state (MT)

Several aspects to take into account up to 2018. Unfortunately, we still have no figures for 2019:

- Deliveries for slaughter have maintained a moderate upward behavior, although with a slight decrease in 2018 compared to 2017. If this behavior continues in 2019, deliveries for slaughter will also have decreased.

- In the structure of deliveries, contrary to what might be expected, it is the state sector that contributes the most with 64.8%. I don’t know the reasons for this apparent contradiction, it could be that a part of the swine produced in the farmer sector is slaughtered outside official places and goes directly to forms of commercialization such as agricultural markets or private restaurants.

- The reduction experienced in deliveries from the non-state sector also stands out, comparing 2013 with 2018. This may be determined by the reduction in contracts or agreements between the state sector and the private sector.

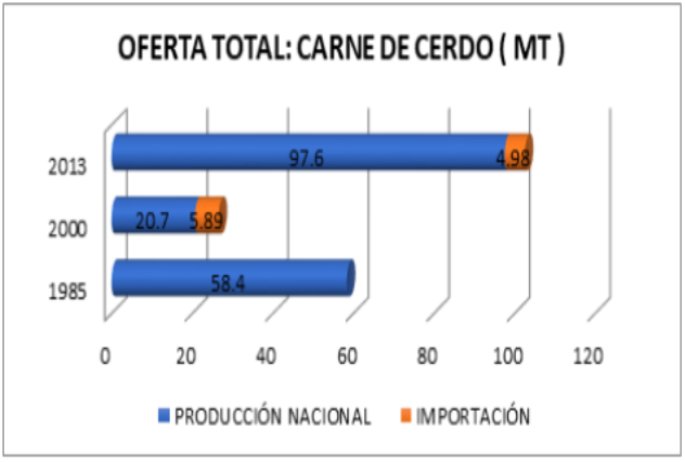

The industrial production of pork between 2014 and 2018 behaved as shown in the following graph:

*Caption:

Pork in bands (MT)

Also in this case production grew. If we compare 2014 with 2018, that growth was more than 30,000 tons. It is not possible to know if this growth corresponds to what is potentially possible, but we do know that it is far from meeting demand and even less the needs of the country.

An important part of pork in Cuba is sold in the agricultural markets. Of the five different types of agricultural markets that exist in the country, for the purposes of marketing pork in pieces, three of them are relevant.

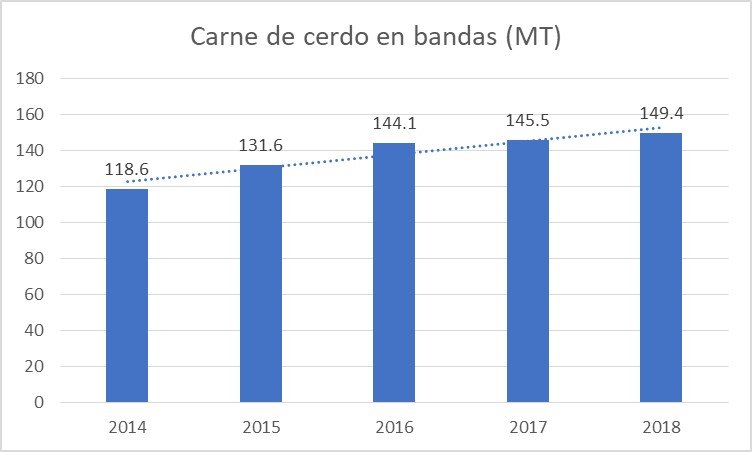

*Caption:

AGRICULTURAL MARKETS

Sale of pork in pieces

Physical (T)

Value (thou. CUP)

Physical (T)

Value (thou. CUP)

State AM

Supply and Demand AM

Sales outlets

Total sales

Some aspects to take into account:

The state agricultural markets are responsible for more than 90% of the total pork in pieces sold in agricultural markets. The sensitivity of demand in the face of any variation in supply must have a direct impact on prices, pushing them upwards.

The other two forms of market (both state-owned) barely reach 10% of total sales between the two.

In 2019, sales of this type of product in state markets decreased by 8%, while in the so-called supply and demand markets and at outlets, they increased by 17.7% and 5%, respectively.

A part of the sales of pork in the supply and demand markets and in the outlets comes from individual breeders, often in patios of houses or in small plots; generally, these animals are not counted within the herd that the official statistics collect, so we have more swine than what the numbers say.

However, the path from the corral to the stand is like that song Farah María used to sing: a “long path”; or like that other famous song by the Beatles: the long and winding road. It includes: breeders, part of whom (and not the smallest) raise swine to survive; to the slaughterhouse; to “private carriers” (a private tractor, a horse cart, a rickshaw, a wheelbarrow); to the agricultural supply and demand market itself and its regulations; and to those other regulations external to that market (which often hinder supply from other provinces to the large Havana market, the largest of all and with the most purchasing power) [3] and price regulations.

Unlike what happened two or three years ago, today the standing purchase price of pork in Havana and its surroundings is between 27 and 30 pesos a pound, the sale price to consumers has been capped at 40 pesos/pound for leg, shoulder and loin and 25 pesos for ribs. The costs of the long road include the payment of the sacrifice and benefit, of the transportation to the slaughterhouse and to the agricultural market (includes the payment for the loading and unloading) and the payment of the stand; all this can generate fixed operating costs that are between 300 and 400 pesos. A swine decreases 30% more or less.

When the standing price of pork was paid at 12 and 13 pesos a pound, long ago, in a distant galaxy, the consumer paid 25 pesos/pound leg and loin, at 22 pesos/pound shoulder and between 15 and 18 the ribs. Then, when the standing purchase prices rose to 22 CUP the sales prices at stands reached up to forty pesos. Today, the situation is different, totally different, since standing prices have reached 30 CUP. So keeping the price cap at 40 CUP for leg and shoulder and 25 CUP for ribs doesn’t seem like a good incentive for pork to make travel that path from the farmyard to the stands. It seems that this matter should be rethought.

It seems inconceivable to me that in Cuba you have to pay a kilo of pork at prices similar to those in Spain. Everything seems to indicate that capping prices does not lead to encouraging the growth of supply in these (supply and demand) markets, which, moreover, is barely 10% of the total supply of pork. It is true that it is a prohibitive price for many Cubans, however, the option of state agricultural markets remains, which is 90% of the offer and that would be susceptible of being directly increased from state productions at more affordable prices, if sufficient production existed.

It is also true that it is not a short-term solution, but neither is it very long-term one, since in 120 days it is possible to fatten a swine (85-90 kilos) even without the best feed.

Relaunching the breeding programs by agreement between the Swine Enterprise and private producers and encouraging purchase prices could increase production and slaughter deliveries again. Three factors here are decisive:

- Sale price of pre-fattening to private producers.

- Purchase price of animals ready for slaughter to private producers.

- Sale price of feed to private producers.

- Certain guarantee for feed.

In the longer term, knowing that feed is decisive and that Cuba imports it, and this is where the bottleneck is, it would be good to study the possibility of linking agricultural producers to the production of corn, soybeans and honey; in addition to the new protein feeds, plus the possibility of recovering the production of torula. Another measure would be that, instead of subsidizing imported feed, very soft credits with long grace periods be granted, at least initially, to national feed producers for swine production. Corn is a short cycle crop, there are varieties already tested in Cuba, which reach up to 10 tons per hectare, more than 800,000 hectares remain uncultivated in Cuba. It is almost Kafkaesque, not having pork for not having feed, having land to plant even quality feed. Even from that soy yearned for so long, already in the 1930s, varieties adapted to our conditions were obtained at the Experimental Station of Santiago de las Vegas that were relatively close to the world yield of that time. Let’s think as a country.

I would like to emphasize that a ton of pork makes it possible to produce 5 tons of meat products.

Pork production is so strategic for Cuba that it was also one of the objectives of the CIA attacks, when it introduced swine fever into the country, which forced the mass slaughter of swine populations and almost brought to zero its production.

Thus, recovering the pork production capacity, practically achieving self-sufficiency, was more than a productive achievement, a symbol of Cuba’s ability to resist and defeat the attacks of the U.S. government against our country. The recovery of that production was also historic.

Guaranteeing “our daily pork” is, without a doubt, strategic and not only now in these times of COVID. There are people with experience in this type of production and every day they are making tests, and they even innovate to make up for shortages. There are men and women to produce, there is land, there is need and there is also demand, it is more than enough.

Undoubtedly, local governments can play a much more active role in this matter, also encouraging this quasi-artisan breeding that can be of great help today.

Let’s improve incentives, update regulations, make the way easier. “We can’t keep doing things the same way.”

Notes:

[1] Processing of the animal for the sale of meat.

[2] We have two sources of data for this, chapters 9 and 11 of the Statistical Yearbook of Cuba 2018 and the publication of Sales of Agricultural Products 2019, all from ONEI.

[3] One day I was leafing through Carlos Rafael Rodríguez’s news clippings, luckily kept at the Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy, and I discovered that trucks loaded from Manzanillo with plantains arrived at the Cuatro Caminos Market, fresh fish caught in Bahía Nipe and transported to Havana, by train, from the port of Antillas and, by the way, everything arrived mostly in good condition.