According to recent reports, 46,000 Cubans have entered the United States in the last five months. At that rate, between January and next December, 110,400 should have entered just in 2022.

Some of those reports call this migratory spike a “Slow Motion Mariel.” Is it really comparable? They mention as factors the Cuban economic situation, described as the worst ever. They attribute its main cause to the island government’s will to “open an escape valve,” which this time is not only economic, but political, since it is aimed at “avoiding another J11.” They affirm that these Cubans are searching for a freedom they do not have, embodied in a life project that they cannot achieve here, and over there they can. In this list of attributed causes, however, two others do not stand out, which would seem less important or non-existent.

One is the fact that the United States continues to maintain a golden bridge for Cubans, leading to what some Cuban-American scholars long ago described as the Golden Exile.

To be treated as refugees, these Cubans have never had to prove that they are dissidents, as they say now, or freedom fighters, as they used to say. Law 89-732 enacted by the Johnson administration in November 1966, and unchanged since then, better known as the Cuban Adjustment Act, is the bridge that leads to that Golden Exile.

It is worth remembering that, in all this time, not only “people who fear being repressed for political or religious reasons” (as the UN defines refugees) have crossed it, but also former leaders, ex-military, ex-communists, former professors of scientific atheism, former State Security agents, former official media journalists, former ideology officials, former scholarship students abroad. They haven’t even had to be anti-government, at least until they left. What has really counted is that they “vote with their feet.” That is to say that their departure can be taken as an expression of their disagreement with the Cuban government and their loathing for communism. Naturally, the more professionals there could be among them — doctors, for example — the better. It has been like this, with some oscillations and adjustments over time, since JFK created the Cuban Refugee Program in 1961.

The other ostensible cause of this rise is the accumulation of candidates to emigrate who have not been able to leave, for external reasons. When the granting of visas in Havana was interrupted, in August 2017, 20,000 immigrant visas had been given each year. If the migration agreement, established in 1995, had continued to be fulfilled, between the summer of 2017 and the next one in 2022, a minimum of 100,000 immigrants should have entered the United States legally. These were forced to remain, thanks to a phenomenon called “sonic attacks,” about which nothing may ever be known.

Curiously, many commentators do not identify this closing of the migratory valve by the other side as a factor in the current “crisis,” despite the fact that this situation has already occurred before, in 1963-65, in 1973-80, in 1984- 1994. Although malicious intentions are attributed to the Cuban government regarding migratory pressure, this palpable fact is not mentioned, aimed at provoking it, with the same political ends of increasing the discomfort revealed by official documents declassified in the United States since 1961.

These two causes, a policy specially designed to remove people from the island and a management of the migratory valve to cause pressure inside, have been present all these years, since the apex of the Cold War.

Returning to the other causes attributed to the current migration which I have already pointed out, the first thing is that they seem disconnected from the previous history. Indeed, if you look back, they tend to fade or not exist at all. Is it that a phenomenon of more than half a century can now have such different reasons?

Despite the rule of three with which some explain the migratory cycles on the Island, neither in the early 1960s nor on the eve of Mariel, at the end of the 1970s, did the domestic market contract or narrow, rather the other way around. In 1980, for example, we were not in the worst of economic situations, but quite the opposite, in the highest and most distributed standard that Cuba has experienced. It would be worth returning to this point later.

As for the escape valve theory, if migration had been used to get the base of the counterrevolution out of the country, Camarioca would have happened in 1962 or 1963, when the civil war called Fight against Bandits was underway, not at the end of 1965, when it had concluded. In any case, at the end of the 1970s, neither the crisis nor the dissent, much less the active opposition, represented a challenge to stability, suggesting an escape valve. In 1980 uncertainty and despair did not prevail. Rather, it was one of those rare periods of relaxation and dialogue, both with the U.S. government and with emigration, which feed expectations of change.

The documents that have come to light about the Mariel crisis show a more complex story than that of “the valve.” The Cuban government was trying to maintain the dialogue, and seek a formula similar to 1965 to ensure orderly emigration, that is, a new agreement. This is how Peter Tarnoff, special assistant to the Secretary of State, and negotiating emissary for Cuba during the Carter era, explained it to me. In 1979-80 Carter did everything possible to avoid the clash that others within the administration were trying to cause, based on the Peruvian embassy incident.

Instead of an economic crisis, an “escape valve,” or the frustration over unrealizable life projects, the relaxation and dialogue of the Cuban government with the emigrants were a favorable factor in Mariel. That dialogue identified them for the first time as “the Cuban community abroad,” after having been for almost 20 years those “worms” who had to be allowed to leave once and for all on the side of the Americans, and to close the door on them forever.

The return of the “worms” renamed “butterflies” by the popular imagination, thanks to the new policy of dialogue, raised a new perspective on the act of migrating: one could leave, without being considered an enemy, and even return later.

None of these changes can be understood without appreciating the differences between the Mariel context and that of the previous flow (1965-73). The years that anticipated the great leap of the Zafra de la Diez Millones (10-million-ton sugar harvest) — without dollar stores, remittances, tourists, farmers’ markets, self-employed workers —, were marked by a deeper and more generalized depression of consumption than at any later time. Unlike the Special Period or the current crisis, a stoic civic culture prevailed then, corresponding to a society that, for the most part, sailed its odyssey towards communism.

Instead, the socialism of the 1970s fostered a different social attitude toward material well-being. In addition to the much-hyped Gray Quinquennium, the 1970s brought with them a new sense of consumption and even of the market, as legitimate practices. As revealed by the investigations of the Internal Demand Institute (IDI) in those years, the new pattern of consumption established at the family level expressed a considerable jump with respect to the 1960s.

In addition to the meticulous ration books of the time (with rum, coffee and cigarettes for everyone), the stores called parallel markets included canned delicacies from Bulgaria, blue cheeses from the Escambray, Kharkov shavers, Thuringian sausages and Albanian jams, Selena radios, Aurika washing machines and Krim TV sets from the USSR, cognacs from Armenia and beers from Bohemia, not to mention the squid and hake from the Cuban fishing fleet that came “by the ration book,” as well as Cuban clothes and shoes, records and books, a month of vacation per year, with massive tourist plans on beaches, within reach of the average salary.

This accessible abundance, however, did not compete with the suitcases of the community members, full of brands and gadgets that suddenly became very popular. Like the Indians who returned to their homeland in Spain displaying their American riches, those huge travel bags brought all kinds of exotic objects, Charlie perfumes, M&Ms, Sony VCRs, Levy Strauss jeans, Puma sports shoes, Beach Boys T-shirts, platform shoes with glitter, Timex digital watches, eyeglasses with mirrored lenses, Pilón coffee.

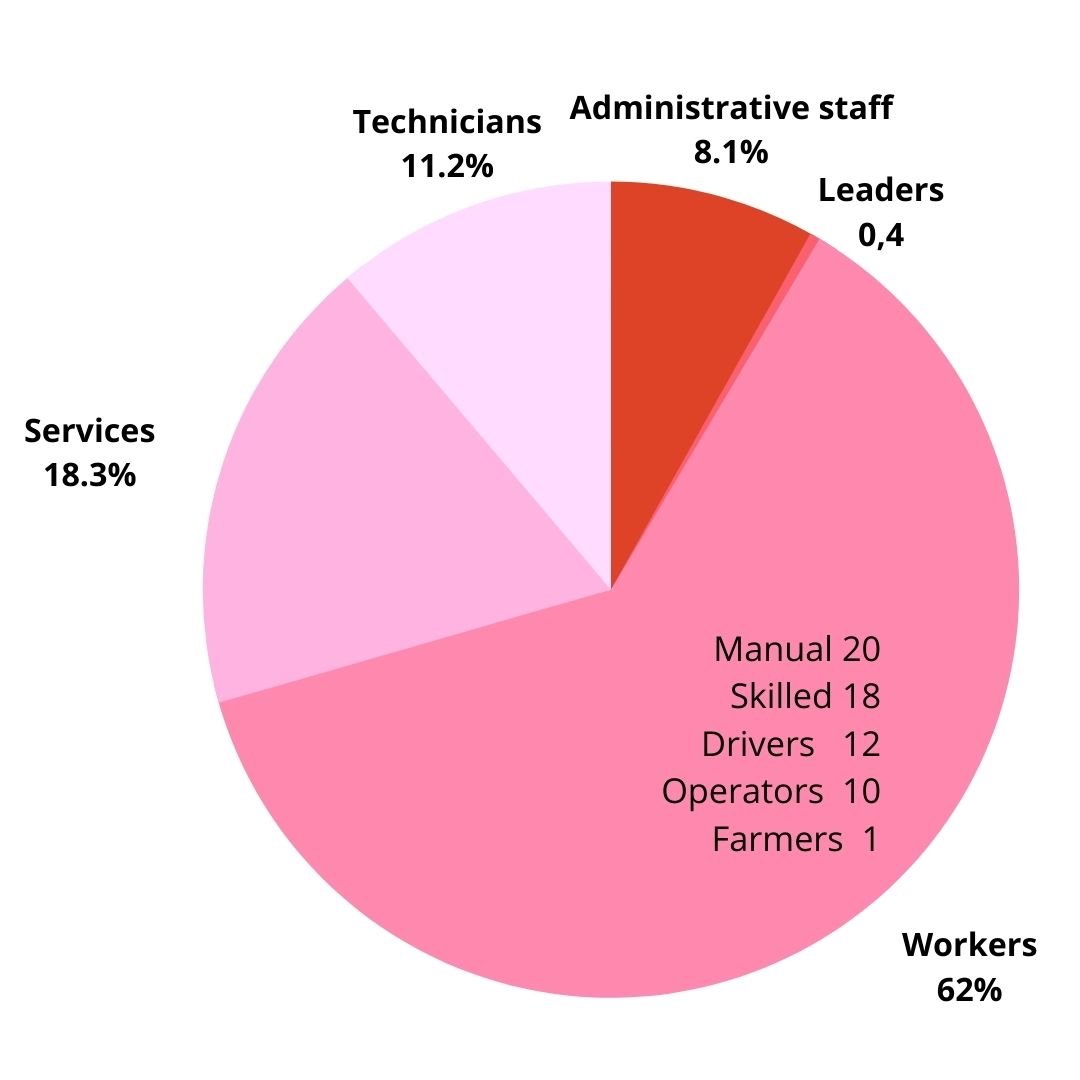

The socioeconomic profile of the Mariel migrants is consistent with the idea of consumption as the main motivation.1

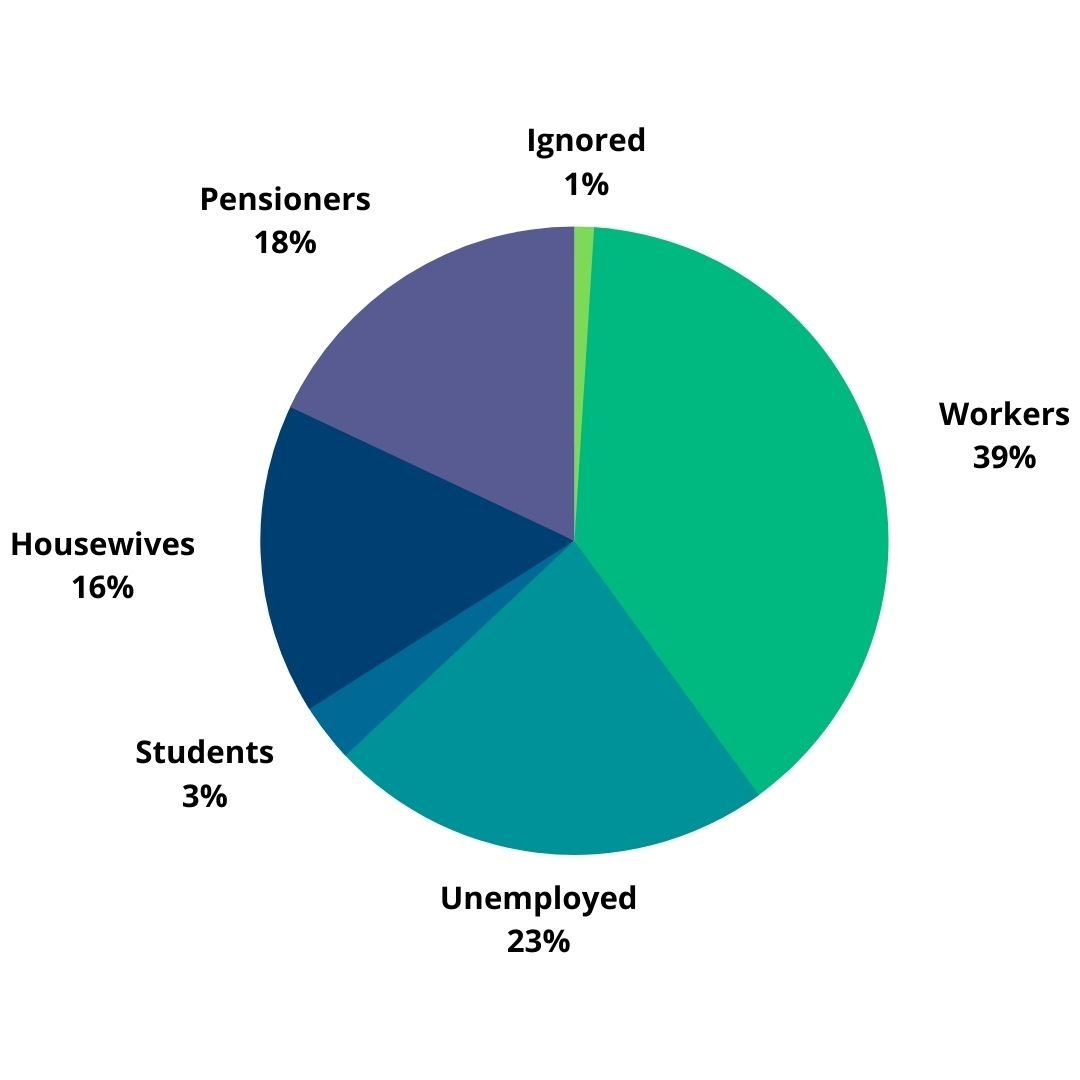

Two-thirds of the “Marielitos” (as they were called in Miami) were people not incorporated into the labor force because they were underage, students, housewives, pensioners, or unemployed.

More than half were between the ages of 20 and 40. Considering the largest age group, the typical “Marielito” was a man between 25 and 29 years old. In the case of women, no matter how old they were, they most likely wouldn’t work. If they were employed, they were probably direct production or service workers.

Compared to the Cuban population of 1980, the Mariel group resembled it more than the emigration of the 1960s: both in the population’s youth, as in the proportion of people over 60 and in their occupational pyramid. At the same time, it was disproportionately male (3.25 men for every woman), and had a lower composition of minors, in addition to high unemployment. Among employees, the composition of professionals and technicians, as well as administrative staff, was lower than in the Cuban labor force. Although higher than previous flows, the proportion of direct workers was also lower than in Cuba in 1980.

Regardless of the greater or lesser influence that the image of prosperity and level of consumption projected by the Cuban-American visitors may have had on the Marielitos’ decision to emigrate, the fact is that the links resumed by those visits created the conditions for the family factor — present in all emigration — would operate more directly. Although this family link is not intrinsically political, its migratory manifestation, in the context of growing U.S.-Cuban tension in 1979-1980, recharged it politically.

In addition to unemployment, a third of the Mariel exodus was made up of people whose ages did not allow them to have a real economic perspective and, therefore, the capacity required to make the decision to migrate. They were an inert segment, dragged along by the impulse of working-age groups and the attraction of the Cuban community. The lack of economic independence of the women seems to indicate that they were chosen, associated or engaged to young men, and relatives residing in the United States.

Although 45.25% of all the people who left Cuba through Mariel had a criminal record, the data reveals that the majority were not in prison. Our investigation of a random sample of more than 5,000 cases showed that the group released from prison to get on the boats did not exceed 15% of Mariel’s total. In the structure of the crimes, theft or burglary predominated (40% of the total with a record), although it could also be minor crimes or non-existent in the United States (dangerousness, illegal departure, contempt, currency trafficking, propaganda, possession of knives, etc.).

Both because of their “presumably lower level of work experience” (compared to previous Cuban émigrés) and their “human caliber” (generalized image that “Marielitos” were dangerous criminals, promiscuous homosexuals, and insane), an immense wave of negative propaganda surrounded the flow also on the other side. This rejection was translated from the outset into limited official political and financial support, the absence of a bureaucratic apparatus that would efficiently manage the aid granted, and the global rejection of U.S. society, which was a greater handicap for their internal promotion.

This generated a rejection at the level of the Cuban community itself, which reflected the interest in preserving the status of “special immigrants.” Many Cuban-Americans claimed that these were “not Cuban,” and that they were “too black.” Subsequently, this rejection would weaken, to the extent that the U.S. government itself undertook, once the seven months of Mariel were behind us, a campaign to rejuvenate the public image of the “Marielitos.”

An action aimed at cleaning up this image was the keeping in prison of nearly a thousand of the new immigrants, who were attributed to have been imprisoned in Cuba, and who, together with the almost 2,000 who were imprisoned for committing crimes in the United States, constituted “the dark face of Mariel,” as the scapegoat for this symbolic cleansing.

The analysis of the context of the exit requires taking into account a factor present in all the previous and subsequent waves: contagion. The lack of direct experience of the destination’s society, as well as the speed of events, contributed to imprinting an irrational component on it that, together with the other causes, largely marked the decision to emigrate. The next event, the rafters crisis, in a very different context, would also bring along common factors.

***

Note:

1 Rafael Hernández and Redi Gomis, “Retrato del Mariel: el ángulo socioeconómico,” Cuadernos de Nuestra América, n.5, January-June, 1986.