In February 1870, in the Isabel II Park, now Havana’s Parque Central, American Isaac Greenwald was assassinated, so it must have been a lynching. Two of his three friends who were walking alongside him were seriously injured. Canarian Eugenio Zamora was insulted with Greenwald wearing a blue tie. Zamora belonged to the sixth company of the Volunteer Battalion.1

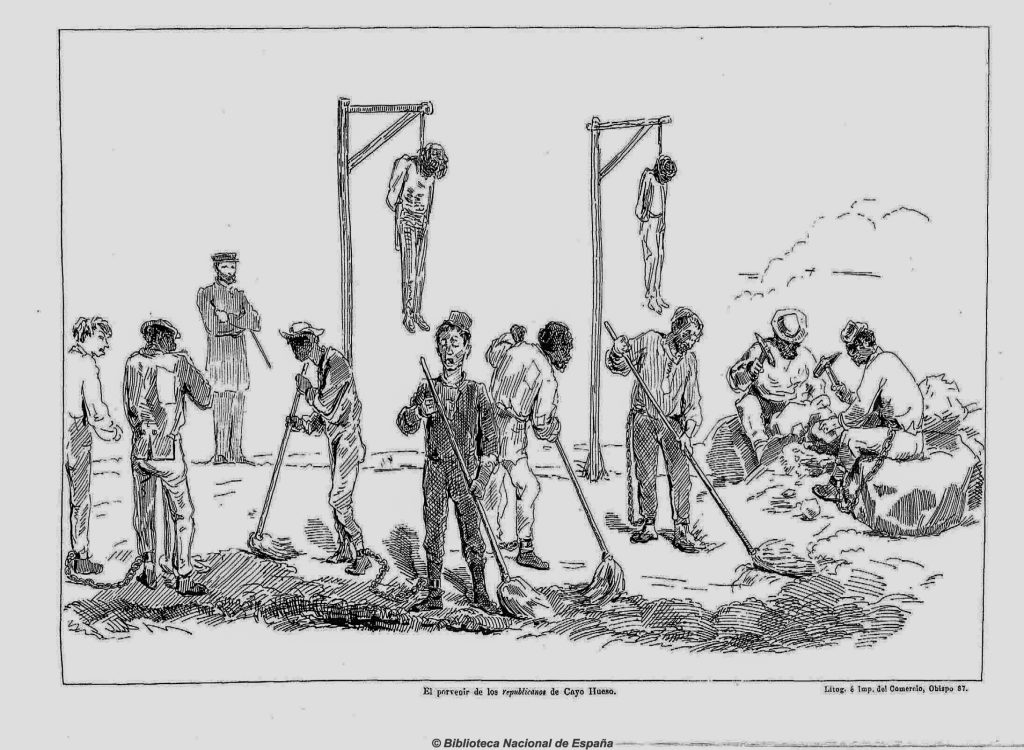

The incident was part of other cases of political violence that led to the death of about ten people in those days, lynched in the middle of a public highway, very far from the insurgent camp. Not all the dead had ties to the Cuban independence movement.

One of those murdered, Luis Luna y Parra, was first attacked with a machete by a corporal of the Volunteers. He was able to barely escape. Shortly after, S. Pedro Covadonga, an Asturian inflamed by the cries of “kill him! kill him! kill that Mambí, insurgent, traitor to the homeland!” stabbed him so many times that he wounded his own hand. Finally, he was finished off by Casimiro, another Volunteer. Once dead, his body received a stab in the chest, four shots and many bayonets. The sequence of his death involved some thirty Volunteers.

The search of young Luna’s body showed these possessions in his pockets: a hundred-peso bill, a twenty-five-peso bill, a doubloon of four, eight reals in silver and a pair of “aretics,” as well as jewelry for personal use: watch, fob, ring, tiepin and cufflinks and a Panama hat. According to the press, the young man came from “a good family.” No ties to the “laborers” were mentioned. It is probable, I can imagine, that at the time of being massacred he was about to woo a girl, because of the “aretics” that he was carrying.

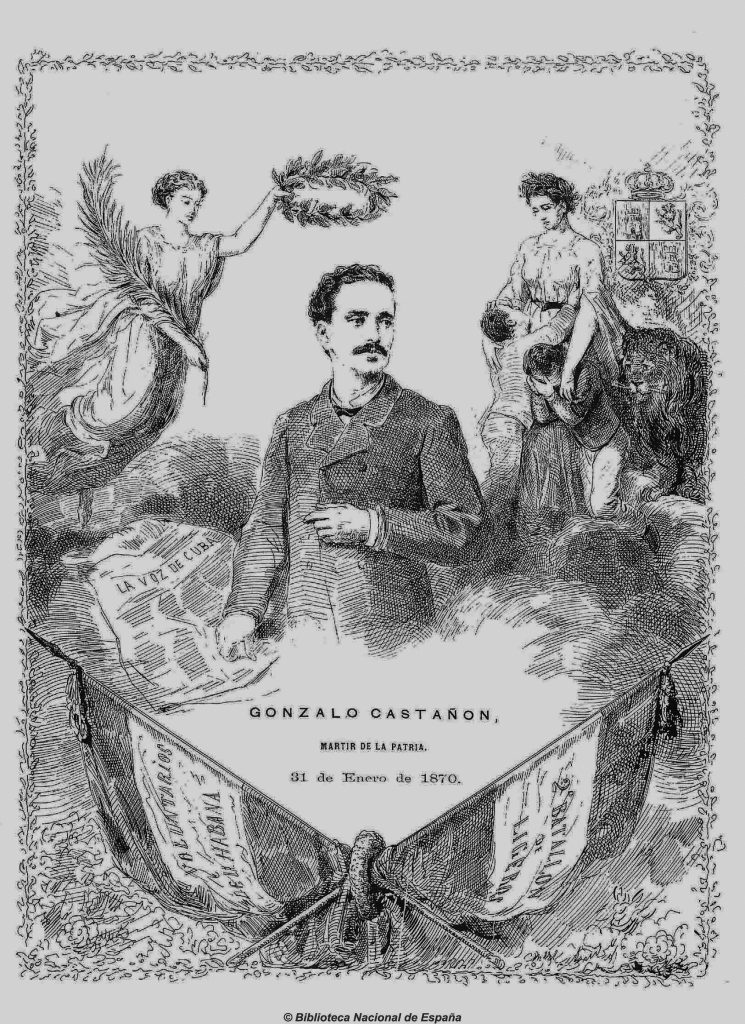

What triggered these events was the arrival in Havana of the corpse, wrapped in ice, of Asturian Gonzalo Castañón, lawyer, journalist and Volunteer colonel, who died in Key West after an irregular duel with a Cuban patriot. The names of the people murdered then are as unknown today as is that of the one that directly caused Castañón’s death, Cuban Mateo Orozco.2

A mention of Mateo Orozco appears in Inocencia (2018), the film―well-made and well researched―by Alejandro Gil, but it is still a very rare reference in Cuban culture.

https://youtu.be/i4n70jSEfKM

However, Castañón is associated with one of the episodes in national history best known to all Cubans: the shooting of the eight medical students (1871). As is well known, these young people were accused, falsely and treacherously, of having desecrated Castañón’s tomb. His death was, in the foreground, open revenge for the death of a leader of fundamentalism, but it had several other aspects that deserve attention.

There is something “unique” about Castañón’s death. He was killed by the baker Orozco, a Cuban worker in Key West. Greenwald was killed because of the color of his tie. Luna y Parra was a young upper-class Cuban. Why did Castañón’s death arouse such a diversity of actors and motives in those dramatic days?

Castañón’s homeland, “without middle ground”

Castañón was considered, by the “loyalists” to Spain, a “martyr of the homeland.” In life, he was a staunch defender of Spanish “integrity.” Committed to such a program, he did not allow “middle ground”: either you were with Spain―with his notion of Spain―or you were against it.

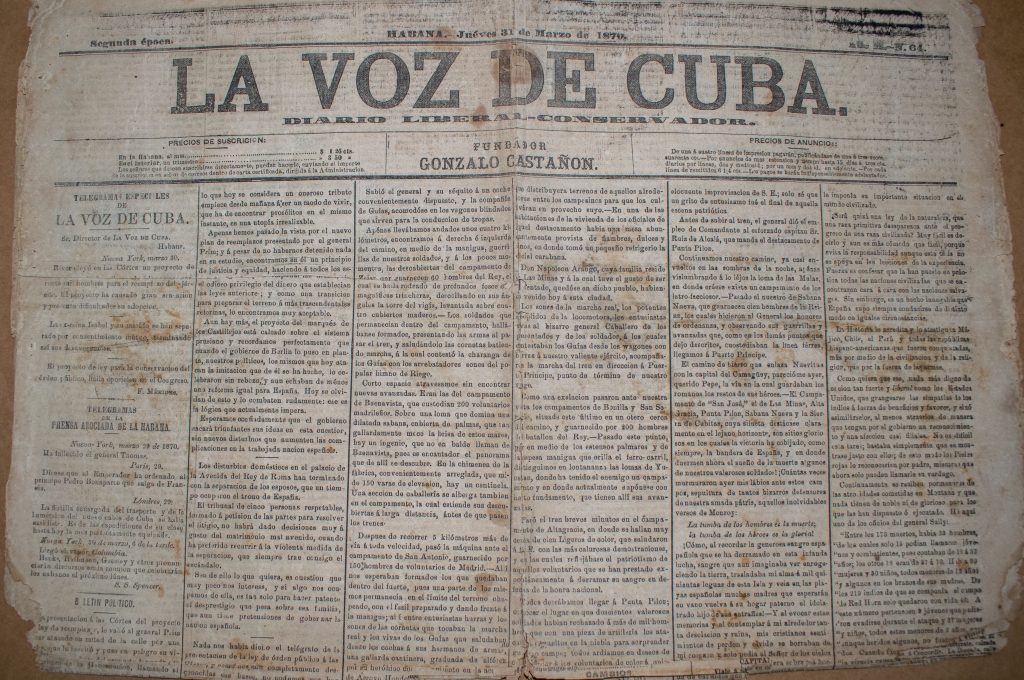

At the beginning of 1870, La Voz de Cuba―a newspaper founded as a joint-stock company, which would become the highest organ of Spanish fundamentalism in Cuba― “advocated the total extermination of Cubans in order to repopulate the island with Spaniards.”

Castañón, its founder and director, summoned his co-religionists in this way: “Let us now abandon middle grounds, and the resolutions that in addition to not satisfying anyone, nothing can be achieved with them either. If Cuba is to continue being Spanish, it is necessary to radically change its organism, and infiltrate new elements of life that will fully replace the degenerates that it contains today.”3

The La Voz de Cuba campaigns capitalized on the anxieties of the hardline Spanish sector within Cuba. Its tone was scandal, defamation, accusation without evidence, the attribution of epithets and the incentive to violence against its enemies. Journalistic practices like this were key in preparing the climate that led to the brutal events of the Villanueva Theater, the Acera del Louvre and the sacking of the Aldama Palace.

A very young José Martí made this criticism of the newspaper, which was called by the patriotic sectors “La voz de Castañón.” In El Diablo Cojuelo, Martí wrote this very serious joke:

“Mr. Castañón?”

“Yes?”

“Here Miss Cuba is looking for you, who comes to demand her voice, which she says, you have taken without her license.”

“Oh, shut up, shut up, friend! Say I’ve moved; that I have gone to hell, that…whatever…anyway…look…if she harasses you a lot, you tell her, for me, that I plan to change my voice, eh? But soon, pronto!”

“We do not know at this time if Miss Cuba entered or not, we will notify this happy event in time.”4

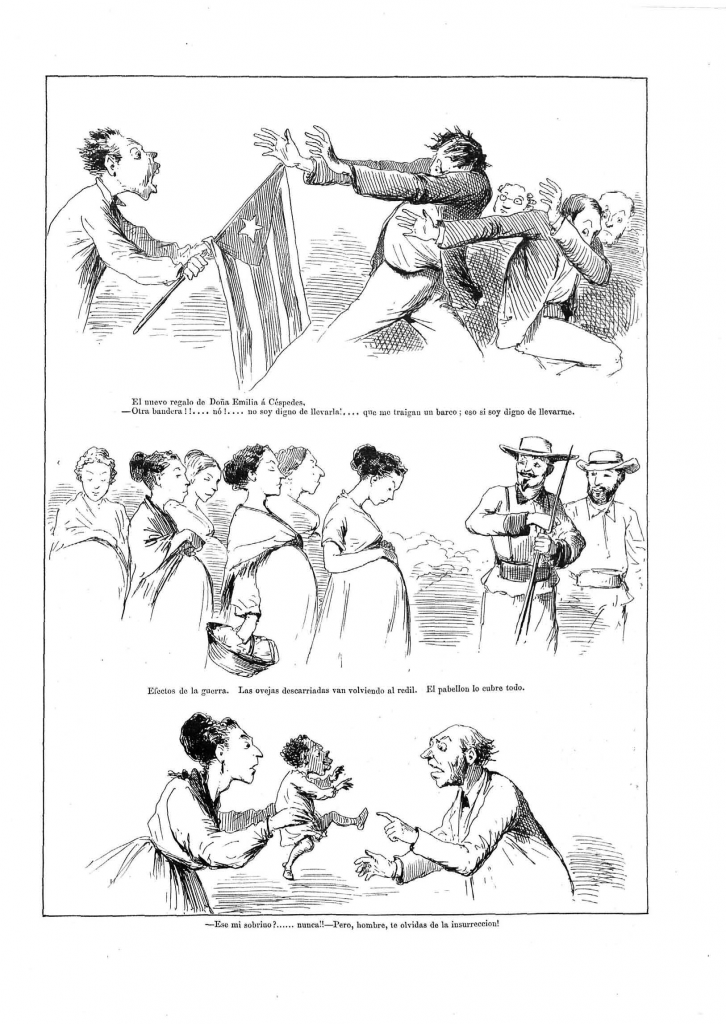

For its part, El Moro Muza, a newspaper with a similar approach to that of Castañón, accused Cubans of “degraded entities, who do not want to be Spanish, and they do well, because we cannot allow them to be so either. They come, without a doubt, from the most uncultivated of Africa, and the land from which they originate is claiming them loudly.”5

In colonial logic, black was synonymous with barbarism, but in Cuba it was also a way of graphically representing the “danger of Haiti.” It presented the Cuban republic in struggle as another “black republic,” a horrible image for the United States, from whose government the Republic in arms demanded during the Great War, without success, recognition.

At the same time, Castañón was crying out against the Cuban colony of Key West, as it was the main reservoir, along with Tampa, of patriotic propaganda, arms shipments and the outlining of revolutionary plans. In one of his outbursts, Castañón called the independentist Cuban women “prostitutes.” His press did not stop representing Cuban women as abandoned by their husbands, in need of Spanish protection, and given over to the promiscuity of the insurrectionary camp, giving birth to children to “the blacks.”

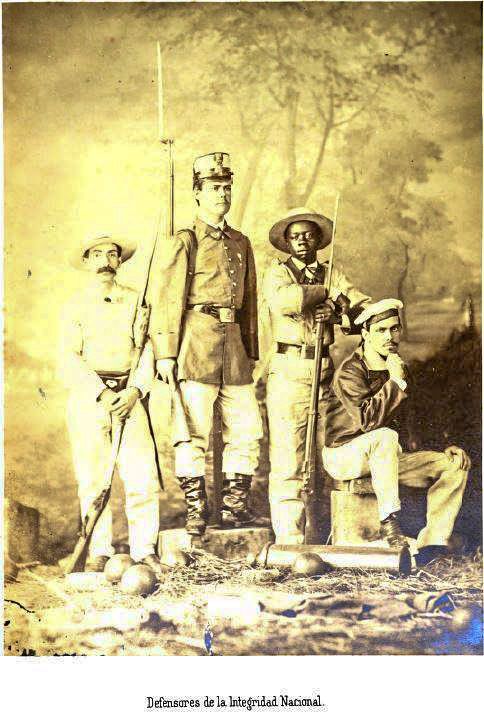

For contemporary research, these intersections of class, race and gender in the anti-independentist discourse are very interesting. Such a discourse was not a mere display of extremist ideas. The Spanish Volunteer Corps in Cuba is known for its ferocity, but somewhat less for its social composition and class structure. However, period testimonies already shed light on this matter.

Spanish historian Justo Zaragoza then called the sector represented by the Volunteers “middle class,” “classified by their peculiar living conditions, in an inferior economic, social and political position than those of the highest sectors of the Cuban community, Spaniards or Cubans.”6

According to the book Historia de la nación cubana (1952), the Volunteers were a social body whose membership greatly consisted of medium and small merchants from Havana, and from cities and towns. Many of them were dependent, engaged in trade and land and cabotage transportation, fishing, crafts and a set of activities considered as “slaves” that, for one reason or another, were not carried out by Cubans. To this were added the subordinate employees of the colonial Administration, and journalists, writers, etc., who had in common having scarce resources.

According to this approach, they were despised by the colonial aristocracy, those of high commerce and slave endowments, and were equally displaced from the decision-making of the colonial regime. Faced with what they felt as a lack of political space, and of social dignity, they questioned the Spanish upper class. Rich Cubans were also the object of their wrath—for having wealth as well as being ungrateful, if not traitors, to Spain. Not any poor Cuban escaped from that anger, but who had occupations that allowed them a somewhat more independent life.

Both the rich Luis Luna y Parra and the worker Mateo Orozco classified in these social circles. At the same time, Greenwald represented the nation that housed that “nest of laborers,” Key West, and had the “gall”—we don’t know if it was a gesture of ignorance of the symbol’s meaning—to display blue, the iconic color of the independentists.

Taken together, with all their diversity, Luna, Orozco, and Greenwald represented an affront to the Spanish homeland—to the specific homeland of the Volunteers. The violence and plunder defended by the discourse of the Volunteers―the seizures of the assets of pro-independentist activists gave rise to colossal corruption scandals―was their “political” way to gain power and representation.

Castañón was perhaps the most scandalous spokesman for that interest. He was considered by that social body as a kind of representative. The journalist said about the Volunteers: “I see them, always generous, share their bread and their clothes with the wife and elderly parents of their own adversaries, carry entire leagues on their shoulders the helpless and young creatures abandoned by men crueler than the very beasts.”7

Extremists are not by definition liars. Castañón seems to have been a man convinced of his ideas. However, no matter how much passion an extremist puts into his statements, they do not ipso facto become true. His words were crude lies. The atrocities of the Volunteers came to astonish someone with proven ferocity as the Count of Valmaseda, and generated denunciations in the Spanish Congress itself.

Contemporary academic research has identified a broad and complex map of the social integration of Volunteers. Catalan historian Joan Casanovas considers that there are three types of Volunteer Corps and three stages: a) those that were founded at the beginning of the Ten Years’ War in Cuban towns, formed almost exclusively by wealthy Spaniards and their employees, but also by large Cuban-born landowners; b) the Volunteers hired as mercenaries who arrived from Spain, financed by the various metropolitan bourgeoisies through the Hispanic-Overseas Centers; and c) the militias that were recruited in Cuba itself, in which a large number of black people were even recruited. The latter, Casanovas adds, is a very little-known group. It is a purely Cuban body that fought against the Republic in Arms.8

The duel with Castañón. The Cuban homeland, and its terms

The support of Cuban patriotism was described by this extremist press as typical of the “rooks of the starry republic.”9 It is an interesting reference, which can be read in various ways. The “rook” is a bird, a kind of corvid, which can be taken as a “big crow,” and has a very strident sound. It was a way of calling the independentists “scandalous,” or “loud”. “Rook” also has the meaning of “charlatan,” which is another way of saying “loudmouth.”10 Perhaps, although it is less likely, the reference to “rooks” evokes, in a pejorative way, the Graco brothers.11

In any case, for the colonial discourse, the Cuban “rooks” were the “[openly republican] rabble of laborers and sympathizers who in past times would ring our ears with their braying.” The same ones who did not have dignity, because the “defenders of the cause of the star do not know, not even by name, that route.”12

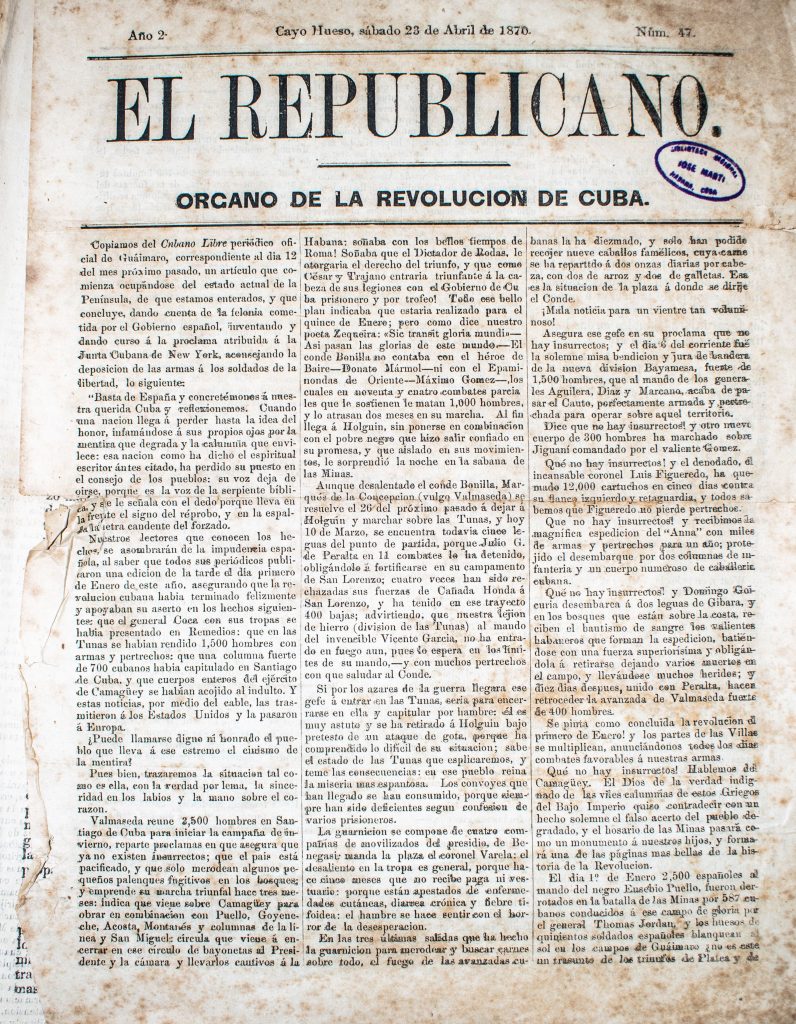

Castañón went to Key West to challenge Juan María (Nito) Reyes, director of the newspaper El Republicano, to a duel, who would have “offended” him in his newspaper pages. Sources indicate that Castañón knew of a previous case of duel, which resulted in good propaganda, and would have calculated that a new duel would serve to gain attention, necessary for his newspaper during the times of low sales. It has even been fantasized that Castañón was wearing a chainmail under his shirt in Key West, as proof of the false readiness for the duel, but this point was denied by his autopsy.

**Already in Key West, Castañón, 33, publicly slapped Reyes, who in several chronicles is described as an old man, although he was not more than 42 years old. Because of this, Castañón was fined 200 pesos. The headquarters of El Republicano was in the house of cigar maker John H. Gregory, located opposite the Rusell House Hotel, on Duval Street. Castañón decided to stay precisely in that hotel. From his windows, it is probable that he saw Reyes’ daughters dressed in white and blue ribbons, which proudly identified the independentists. The daughters of Reyes were also included in Castañón’s classification of “prostitutes.”

The news of the humiliation against Reyes, plus the ostensible provocation of Castañón supposedly walking in front of the headquarters of El Republicano, could not help but inflame the spirits of the patriotic Cuban community in Key West.

Thus, the challenges to a duel against Castañón followed, which he declined consecutively. Mateo Orozco was among those who launched the challenge. Here is another class detail: Castañón treated him with contempt. He probably considered that a baker did not deserve the honor of a duel. During a brawl at the Russell House, where Orozco had gone to appeal to him, he shot Castañón twice, which would eventually end his life. Cuban oral memory assured that Orozco would have shouted at the end: “Cuban women, you’re already avenged! Long live Cuba!”

Collective responses to individual events are a mark of revolutionary solutions to the problems that those responses address. The Cuban collective patriotism has an essential content in the political fraternity―which considers the free as reciprocally free, that is, as equally free.

Orozco’s “personal” act received massive, enthusiastic support from the Cubans. It was toasted in the bars of Key West with Cuba Libre. José Dolores Poyo, who would later become a close friend of Martí, hid, with all the risk that this entailed, the revolver with which Orozco killed Castañón.13 Among several, Orozco was secretly taken out of the United States. A chronicler of patriotic emigration in the United States said: “Once again Key West put the enemies of Freedom at bay.” 14

Castañón’s body was received in Havana by the highest colonial authorities. The Volunteers unleashed the wave of terror described at the beginning. Castañón’s two sons were placed under the protection of General Antonio Caballero y Fernández de Rodas. (Later, one of them, Fernando, would be decisive for the clarification of the innocence of the eight medical students.) Meanwhile, patriots with a good memory raised a monument to the martyrs of the Cuban homeland in the Key West cemetery. In a modest stone memorial book, where the names of these martyrs are modestly recorded, there appears that of Mateo Orozco, the baker, the defender of Cuba, of the Cuban men and women, the hero of the homeland.

In a book published in 1911, Cuban historian Enrique Ubieta assured that Castañón’s corpse received honors from the “Captain General to the last Volunteer,” who paraded “day and night before the coffin.” However, no Cubans approached his grave, “for everyone knew that he professed hatred of those born in Cuba.”15 The color blue, which cost Greenwald his life, roamed at ease in Key West, and surely firm, although secretly, in Cuba.

It is the blue, which until today, together with the red and white, identify the flag of Cuban collective patriotism. This is how musician José María Vitier García-Marruz describes the meaning of that blue, beyond his piano, with his own words:

Blues

There’s Bottichelli’s spring blue

Van Gogh’s nocturnal blue

Scriabin’s blue prelude.

There’s a poisoned blue taste

and a blue perfume capable of everything.

There’s a blue washed by the foam,

and a blue that descends up in the sky.

And that intense and brief blue of the small flowers,

and that blue moment of some evenings.

Just as there are looks,

impossible looks like verses

blue like tears and blue silences.

But this evening it was the Havana

winter blue,

the one that, I don’t know why, has reminded me of another

blue.

indigo of another innocence,

thread blue,

future flag,

hand sewn,

by all Cubans.16

***

Notes:

1 This text owes everything to the great historian Luis Felipe Le Roy y Gálvez, specifically to his studies on the death of Gonzalo Castañón and the shooting of the eight medical students. Also, to Historia de la nación cubana (1952) (Ramiro Guerra and others), Volume V, Havana: Editorial Historia de la Nación Cubana, S. A., p. I rely on them for the central story that I follow here, so I avoid repeating quoting both texts.

2 In journalism, the figure of Mateo Orozco has chronicles such as that of Ciro Bianchi and that of historian Antonio de la Cova. Recently, the book Con un himno en la garganta. El 27 de noviembre de 1871: investigación histórica, tradición universitaria e Inocencia, by Alejandro Gil, is of great interest, although it does not stop at the fact of Castañón’s death, the beginning of the events of November 27, 1871.

3 La Voz de Cuba, January 5, 1870, p. 1

4 José Martí. “El Diablo Cojuelo,” Complete Works (1991) t. 1 p. 33.

5 “I insist on it.” El Moro Muza, Epoca VII. February 6, 1870. No. 1

6 The specific references that appear here to the class composition of the Volunteers can be found in the aforementioned Historia de la nación cubana. (1952), Volume V.

7 Álbum Vascongado. Relación de los festejos públicos hechos por la ciudad de La Habana en los días 2,3 y 4 de junio de 1869, con ocasión de llegar á ella los tercios voluntarios enviados á combatir la insurrección de La Isla, pp. 21-22

8 Personal communication of Joan Casanovas with the author of this text. I thank, as I have done on other occasions, the professor’s generosity in sharing knowledge of his long and valuable research work on Cuba. For an academic version of his arguments on the subject, see Joan Casanovas Codina, ¡O pan, o plomo! Los trabajadores urbanos y el colonialismo español en Cuba, 1850-1898, Madrid, Siglo XXI de España, 2000, 326 pp.

9 Juan Palomo, Year 1, Havana, April 17, 1870. Num. 24.

10 This paragraph has been modified, with respect to the first published version of this text, after an interesting exchange with two colleagues. The opening paragraph suggested the association between “rooks” and the “Graco brothers.” I will continue to investigate that possibility, but pending further confirmation, I prefer to show here a diverse field of plausible meanings for that expression of “rooks of the starry republic.” (Note from 7 pm on 01.06.2021.)

11 The Gracos brothers staged a “great antiplutocratic revolution” in times of the Roman Republic. In Cuba, Julio Antonio Fernández Estrada and Julio Fernández Bulté have given a nuanced description of the progress, contradictions and hesitations of the Gracos. For example, here: Julio Fernández Bulté (1984) Historia de las ideas políticas y jurídicas (Roma), Havana: Pueblo y Educación, pp. 103 et seq.

12 Juan Palomo, Year 1, Havana, April 17, 1870. Num. 24, pp. 190-191

13 Historian Gerald E. Poyo, a descendant of José Dolores Poyo, has confirmed this point: “According to the oral history of the family, the gun remained in the hands of José D. Poyo. This was confirmed to me by Luis Alpízar Leal, J.D. Poyo’s great-grandson and archivist at the National Archive of Cuba, whom I met in 1982 until his death in 1987. Luis saw the gun (around 1955) in J.D. Poyo’s personal archive that the son of Francisco A. Poyo (my great-grandfather) kept in his house. Francisco passed away in March 1961 (at 89). The family left Cuba, and the archive disappeared with the famous gun. Perhaps someone in Cuba has it without having the slightest idea of its historical significance.” (Communication from Gerald D. Poyo with the author of this text.) In Exile and Revolution. José D. Poyo, Key West, and Cuban Independence (University Press of Florida, 2014), Gerald E. Poyo, affirms that Orozco, after the shootout with Castañón, went to José Dolores’s house and that he arranged for him to leave the United States. (p.23)

14 Gerardo Castellanos, Guerra de los Diez Años y la Guerra Chiquita (without further information in the consulted copy), p. 696

15 Enrique Ubieta, Efemérides de la Revolución cubana, 1911, Volume I, La moderna Poesía, p. 13

16 Taken from José María Vitier’s personal Facebook wall, reproduced here with his permission.