In 2016 the magazine Revolución y Cultura (RyC) ―then directed by Luisa Campuzano and by an Advisory Council composed of Graziella Pogolotti, Ambrosio Fornet and Antón Arrufat― dedicated a dossier to the 130th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Cuba. [1]

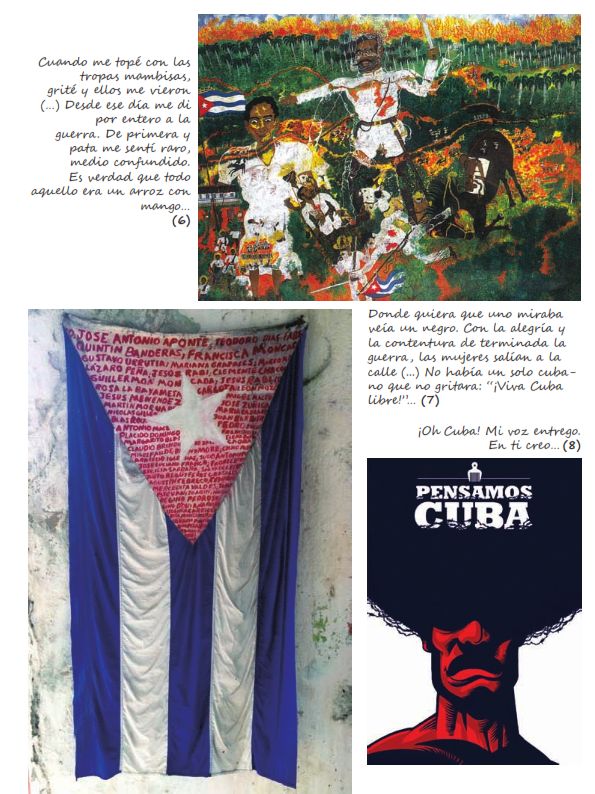

“Historieta de un esclavo en Cuba,” by Israel Castellanos León, appeared among its pages. It is a montage of plastic works, accompanied by texts dedicated to slavery and its resistance. There you can see “La sangre negra de la historia” (2014, mixed media, 150 x 60 cm), by Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara (LMOA). Manuel Mendive, Alberto Lescay and Édouard Laplante are other artists participating in the material.

That LMOA work is a Cuban flag. In its triangle, with a white background, names such as José Antonio Aponte, Quintín Banderas, Gustavo Urrutia, Mariana Grajales, Blas Roca, Carlota, Antonio Maceo and a long list of black and mestizo heroes of different ideological affiliations are written in red ink. The background of the work is a humble wall, typical of a common Cuban home, from which the flag hangs. The accompanying text belongs to Biography of a Runaway Slave, by Miguel Barnet.

Only five years after the RyC dossier was published, voices from official institutions in the country ―the same as that magazine belongs to― have taken away from LMOA any status as an “artist.”

The artivist has been prosecuted ―with a request for sentences of between two and five years― on charges of violating the National Symbols Law and damaging state property under the Penal Code. A few days ago, for the moment, the trial has been suspended.

The first of these accusations has more public information than the second. The “outrage” that his performances represent for the flag that use it in daily and intimate situations, such as covering oneself with it to go to the bathroom or lying on it on the sand at a beach, has been cited. Certainly, they are unorthodox uses of the symbol.

The national flag: resistance and heterodoxy

Ironically, the national flag also has its own history of heterodoxy.

First raised in New York, it was conceived by Venezuelan general and freemason Narciso López. In 1848 López had hired mercenaries among veterans of the Mexican war for a project to rid Cuba of Spanish colonial rule. He offered them, according to Lisandro Pérez, the regular pay of the U.S. Army, in addition to promising them future ownership of land in Cuba.

In 1850 an expedition under his command would land through Cárdenas, this time already in the midst of conflicts with the Cuban annexationists in New York. On that occasion —for which López sought support from southern slaveowners in the United States— the flag arrived in Cuba. The Constitution that López brought with him also affirmed that Cuba should be a Republic, but was silent about slavery.

The Venezuelan died executed by the colonial power in search of what Emeterio Santovenia called “the international sovereignty of Cuba.” Jorge Quintana defended that “he was not a filibuster, but a patriot.” Herminio Portell Vilá dedicated three volumes to demonstrate that he was not an annexationist. However, the label of “annexationist” still haunts López to this day, although recognized patriots were in his circle.

Cirilo Villaverde, author of Cecilia Valdés, explained the original content of that flag: the three blue stripes represented the regions of Cuba, and the two white ones are the “symbol of the purity of the intentions of independent republicans.”

Emilia Casanova received virulent condemnations for her heterodox political life: she founded the first Cuban Women’s League and is the pioneer of Cuban diplomacy, in addition to having sewn countless flags with her hands. Those who condemned her preferred the destruction of Cuba to a Cuba with Emilia Casanova. Ana Cairo Ballester saw in her the “dignity of Cuban women” as well as a “challenging paradigm of republicanism.”

Domingo Goicuría shared the works of Narciso López. He was persecuted and imprisoned. He came ready for the war of 1868. In prison, he did not seek —worthy among the worthy— defense when judged by a verbal council of war. The oral memory would tell that, on the way to the gallows, he assured that the statue of Carlos III would be replaced by that of Céspedes. Before dying, he would have said: “A man dies, but a people is born!”

He was right: everything that can be called “the Cuban people” ―the class, racial, cultural, regional exchanges that it implies, as well as its political constitution as a subject― was not born in beautiful colonial houses or in humble huts. It was born in what that people called the redeeming scrubland, the Cuban political city of the 19th century, which developed democratic citizenship as an egalitarian.

The flag of the “annexationist” became a sign of nationalism. It represented the greatest conceivable heterodoxy at the time: the libertarian, anti-colonial and anti-slavery Republic. The newspaper La Revolución, from New York, would add content to the meaning of its triangle (1870): “One of its sides is Liberty, another is Equality, and the third is Fraternity. The base of the Cuban triangle is the Republic; the vertex the abolition of slavery.” The same flag that came from Cárdenas later covered Francisco Vicente Aguilera’s coffin, which Martí called the “Father of the Republic.”

The democratic meanings of the war —egalitarian character, defense of social rights, anti-racism, appreciation of the Law and order— marked the democratic uses of the flag that became the flag of all Cubans.

The testimonies of devotion to her are as infinite as fair.

That flag vindicated the heterodoxies of the right of resistance and the inclusion of everyone embodied in the nation and represented personal, national and social freedom. That’s why it is a national flag, not a party flag. Without the continued exercise of those values, it is just a piece of cloth. Homeland is a very demanding political passion. It is a democratic passion when defending those values.

The democratic meaning of patriotism

From another side of patriotism, Gonzalo Castañón —the alleged desecration of his grave triggered the execution of the medical students (1871) ― could say that Spanish soldiers, and especially volunteers, “die for the [Spanish] homeland and that their memory will never be erased from our hearts.”

Verses of colonialist soldiers shared this sense: “In the Plaza de Matanzas/ I met a black man, he told me; Long live Cuba/and I shot him.//Because of the little confidence we have in that people,/ we Spaniards do/as blacks do to us.” The book that collects them is titled Amor por la patria.

It is also a concept of homeland. It is the ethnic, racialized homeland, focused on biology, language, inheritance. The conservative homeland. The excluding homeland of improper emotion, of reason without dialogue. That of freedom as a privilege of sect.

It was the homeland committed to colonialism and then to Francoism: “the peoples of America,” Franco would say in 1939, “are born of our same lineage, formed in the same faith, educated in our same language and therefore participants of the same culture.…”

It was the “German homeland” of Hitler and Goebbels: “We are going to fight for the preservation of the existence and development of our race and our people, the food of their children and the maintenance of pure blood, freedom and the independence of the homeland….”

It was the homeland of Stalinist Russification, another form of official patriotism. It is the xenophobic homeland of Trump, who shouts “go back to your country” to a Latina born in the Bronx.

Those homelands are daughters of despotism. Democratic patriotism does the opposite. Find the homeland where you are free.

It is patriotism that José Martí expressly defended: “They say that the separation from Cuba would be the division of the homeland. It would be so if the homeland were that sordid and selfish idea of domination and greed.” It was also that of Heredia: “From my homeland/under the cloudless sky/I could not resolve to be a slave/nor consent that everything in nature/was noble and happy except man.” It was also that of Villaverde, for whom the patriotism of his character Leonardo Gamboa was only “platonic,” since it was not based, as it should be, on the feeling of duty or on the knowledge of rights as a citizen and as a free man. It was, in the same vein, that of Calixto García: “When you are going to be a citizen of a free people, it is necessary to respect the laws and exercise the virtues from the battlefields.”

That is, patriotism is democratic when it is a political passion for freedom.

It was those cosmopolitan ―universal, therefore democratic― ideas about the country. Such was the homeland of the Jacobins: “The war we are waging is not a war between king and king or between nation and nation; it is a war of freedom against despotism. There is no doubt that we will be victorious. A just and free nation is invincible.” It was Marx’s idea of “the workers have no homeland,” of Kant’s cosmopolitanism, or that of Martí’s “homeland is humanity.” It was this meaning that Roberto Salas defended when he placed the flag of the July 26 Revolutionary Movement on the crown of the Statue of Liberty in New York (1957), which became a symbol of the Cuban underground revolutionary struggle.

The homeland, a common good

LMOA’s recent performances with the flag are consistent with that piece of his in RyC. At that time no one questioned his status as an artist. Both are statements about the flag as a common good, about the homeland that belongs to everyone, with diverse political marks, but without ideological, class, or racial monopolies.

In any case, they should be judged as art —bad art, if it were— but it is a mistake to draw punitive consequences based on their perceived literal meanings. Art critics, such as David Mateo, or artists, such as Cirenaica Moreira, have brought order to the branches of that forest. More than error, it is a horror to turn art critics into criminal law judges.

There are doors that cannot be opened.

Being against LMOA’s incarceration is not the same as sharing his political agenda. His work can be very interesting, or not; in bad taste or with civic substance; but that’s not what’s important here.

What should interest us are central questions that his case brings to the fore: how pluralism and difference are processed in Cuba, how resistance is exercised against what is experienced as unfair, what is the legitimate space to dissent, what right we have to participate in the public space, what should be the width ―the virtue― of the patriotism that we want to defend in the homeland that we want to live.

We should also be interested in the right to dissent from the LMOA political agenda without being slandered for it. Opposition to an injustice does not justify the “anything goes” advocated by currents of opinion contrary to the Cuban government, and which operate with the same “with me or against me” that they claim to contest. We should be interested in the country being an altar stone, not a tribe.

The right to freedom of expression follows from the idea of homeland as a heroism of freedom. That right is of interest, but other rights should also be of interest to us. The preference for ownership exercised in common over private property also follows from this idea of homeland. Love for the municipality as an essential form of political life. The passion for Law, for its democratic elaboration and for its universal compliance, without selectiveness. The devotion to civil and political equality. The demand for freedom of the other as a condition of possibility of freedom itself. Fidelity and loyalty to the norms and institutions that make us free. The appreciation of pluralism. The cult of the full dignity of man. The homeland with all and for the good of all.

Note:

[1] Revolución y Cultura, No. 2, April-June, 2016.