Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina were major centers of slave production. Today they are among the poorest states in the United States. The long trace of slavery is an unavoidable part of the explanation of poverty. The deep unease towards that past is expressed today in several ways.

The demolition of statues of slave-trading figures constitutes one of them. The murder of George Floyd has fueled that intention, prompting the removal of statues of Confederate people and monuments such as those of Robert E. Lee and John B. Castleman, the Bentonville Confederate Monument (Arkansas), and the Athens Confederate Monument (Georgia).

The process has been seen by some sectors as the latest radical fad. Its critics say that it will end up knocking down everything, including Cervantes. A sign with “bastard” was already hung on a statue of the genius. It’s certainly foolish. Cervantes’s most famous character “vowed…to favor the needy and oppressed from the elders” and it seemed “a hard case to turn into slaves those whom God and nature made free.”

The excesses of anger are fertile ground for classist and racist discourses on “correct” civic behavior. It’s forgotten that anger, as a moral outrage in the face of injustice, has always been part of citizen virtue.

Aristotle rebuked the “excessive ease” for anger—as “bad disposition”—but he also did not approve “if nothing moves us.” His judgment valued “just anger” as part of virtue. Dragging Cervantes into anger is “bad disposition,” but slavery, its consequences and monuments provoke just anger.

An old fad

The demolition of statues has been “in vogue” everywhere and at all times. Trajan’s column in Rome (114 BC) was crowned by the statue of this emperor until it was replaced by that of Saint Peter. During American independence, the bronze statue of George III of England, in Bowling Green Square (south of Manhattan), was dismantled and turned into ammunition.

No power has been resisted without also confronting the symbols that represent it. In this, vandalism “from above”—by the hand of the actors with power—is different from vandalism “from below.”

The first type has been praised “among the great milestones in history,” but the second has been denounced as “blind vandalism.” Vandalism, it turns out, is “a privilege for the victors and a sacrilege for the vanquished.”1

The debate has come to Cuba as a discussion about the statue that is part of the monument to José Miguel Gómez, in Havana. There have been many who see criticism of him as importing “American fashions.” The idea that it’s a “fashion” is ironic, if we take into account that for almost 200 years Cuba has seen statues replaced or demolished.

The Queen Elizabeth II statue is just one example. First placed in the current Parque Central (1857), at the fall of the Bourbons, Captain General Lersundi sent it to the prison chapel in Havana (1869). With the return of the Bourbons, it returned to its original place. After independence, it was dispatched “as a useless piece of junk” to the municipal moats.2

In 1905, on the pedestal “belonging” to Elizabeth II, the statue of José Martí was placed there, until today . Similarly, the statue of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, in what is known as the Plaza de Armas, replaced the effigy of Fernando VII.

In the 1930s, following the overthrow of Gerardo Machado, monuments associated with his name were destroyed. The same happened with the face of the dictator engraved on the main door of the Capitolio.

After the revolutionary triumph of 1959, only the shoes of the statue of Tomás Estrada Palma was left and the eagle of the monument to the victims of the Maine was brought down.

With such a history, Cubans should be more careful to describe as “fashionable” the new political currents of interpretation of the symbols of the past.

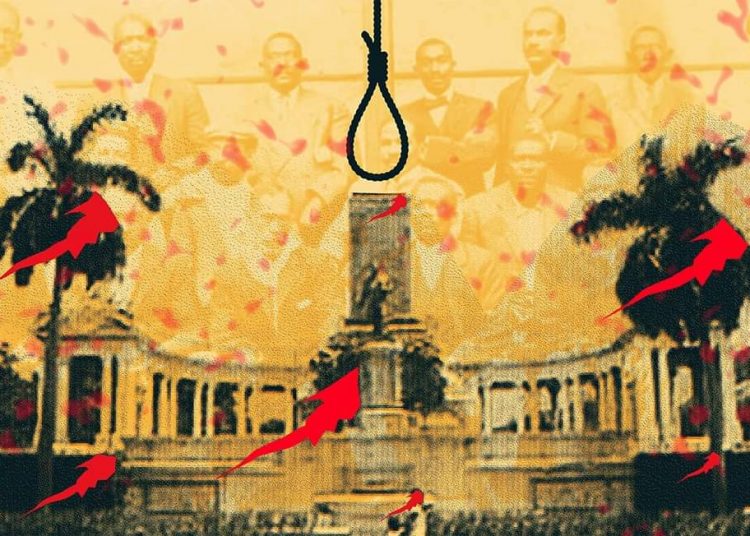

In the Video: The fall of Machado, in images. At the end of the material, Cubans hammer an effigy of the despot.

Gómez and the protest of 1912

José Miguel Gómez was no less than in the three Cuban wars for independence.3 He went from being a private to a general. The Revista de Cayo Hueso claimed that he was highly respected by Máximo Gómez. This is extraordinary praise.4 However, his figure shows problems common to the post-independence oligarchic republics in Latin America.

J. M. Gómez practiced the kind of nationalism—let’s leave out, for now, his well-known corruption—that played with the Platt Amendment as guarantor of the status quo of the time.

“Tiburón” participated prominently in the “revolution” of 1906. In this context, Estrada Palma’s intransigence in the face of the electoral farce in his favor, on the one hand, and the attitude of the liberals—José Miguel was one of their leaders—, on the other, sought for U.S. intervention to come in their respective support.

This was requested by Estrada Palma, but also by J.M. Gómez, along with Alfredo Zayas, “according to the terms of the Platt Amendment,” at a meeting on September 25 with the U.S. Minister Squiers.5 His government was born from the redesign made by the second occupation (1906-1909) of the Cuban political system, to avoid “convulsions” and resolve rotation among elites.

The protest of 1912 had various contents. One of them was to demand participation in that political system. But it was also several other things.

In the first place, a set of actions that combined the action of the Independent Party of Color (PIC) with farmer protests and other subjects affected by the boom in capitalist expansion towards eastern Cuba.6

Second, a test of the depth of anti-black racism in Cuban political culture.

Third, the first great challenge to the oligarchic and racial character of Cuban capitalism, and of the Republic that administered it, after 1902.

Finally, as Fernando Martínez Heredia said , it was “a great warning that clearly established the limits that those from below could not transcend in the Cuban republic.”

The state and the dominant society responded by treating it as a “race war.” J. M. Gómez liquidated it with the largest racist state massacre in national history.

At the same time, the label of “pro-annexationist” has fallen until today on Evaristo Estenoz, one of the main leaders of the protest liquidated by J. M. Gómez. Estenoz would have requested the intervention in the famous letter of June 15, 1912.

The PIC, like the rest of the political actors of the moment, operated “within the clause”—the Platt Amendment. In fact, he had been born during the American occupation. Julián Valdés Sierra, another of its leaders, recognized the Platt Amendment as the great factor in Cuban politics. It did so in defense of the legal existence of the PIC, against the Morúa Amendment, which banned it from political and electoral life.

At the same time, many of the PIC references attest to the commitment to national sovereignty and against the interference of the United States in countries of the region such as Nicaragua. Within Cuba, the PIC denounced the situation of occupation of territories in Pinar del Río and Guantánamo by the U.S. government.

Understanding the PIC’s relations with the United States—like the rest of those actors—requires great attention to context. Presenting it as a matter of nationalists vs. traitors—whether they were one or the other—refuses to think critically about the “problematic nationalism of the first republic,” as Martínez Heredia called it.

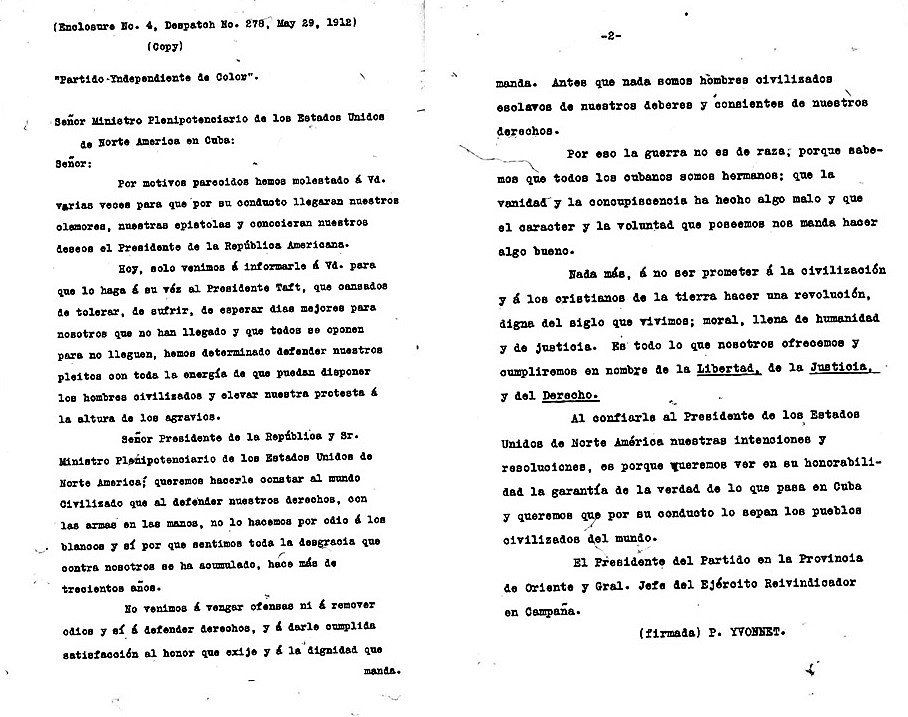

A specific point can now be cleared: Estenoz’s letter, mentioned above, was not written by him.7

Pedro Ivonnet, another of the PIC leaders, had been part of the Invading Army led by Antonio Maceo and was head of a Regiment in the war in Pinar del Río. He addressed another letter to American Minister Arthur M. Beaupré to inform him of the motives and intentions of the protest. There is no word in this letter asking for intervention.8

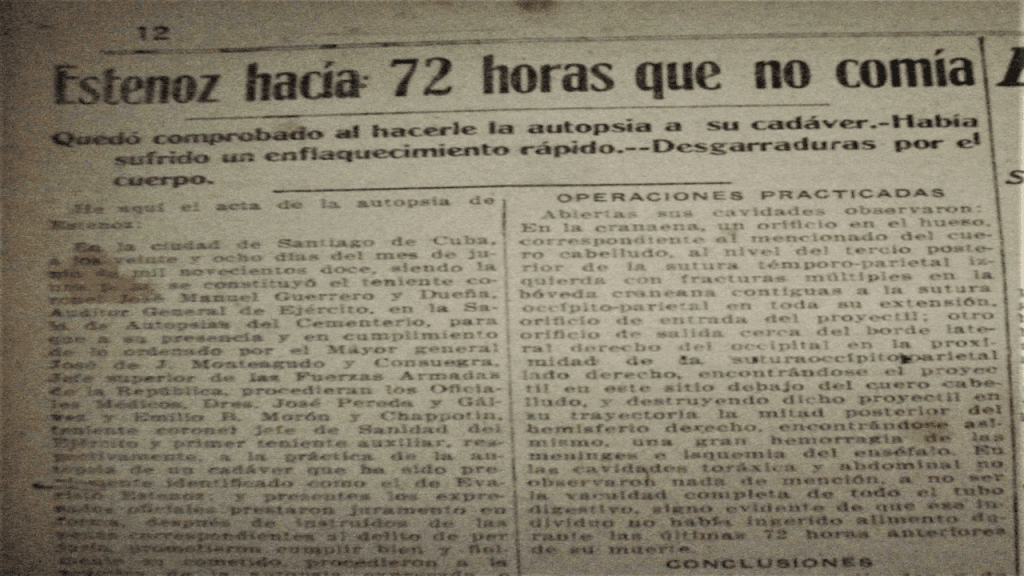

José Miguel Gómez died in 1921, honored. Estenoz, a Mambí Liberation Army fighter and later a fighting worker, described as an anarchist, was assassinated in 1912 by Lieutenant Lutgardo de La Torre.

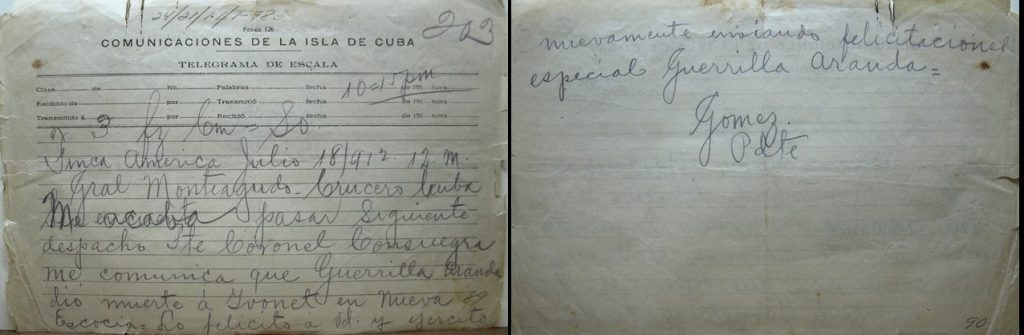

Ivonnet had not eaten for several days when he was killed. Aranda, the guerilla captain who captured him, asked Lieutenant Colonel Consuegra if he could take him alive. The answer was an order, executed in the end by Arsenio Ortiz: “That he not arrive alive in any way. The glory is his and nobody can take it away from him.”9 José Miguel Gómez congratulated Captain Aranda after Ivonnet’s death.

The monument to José Miguel Gómez

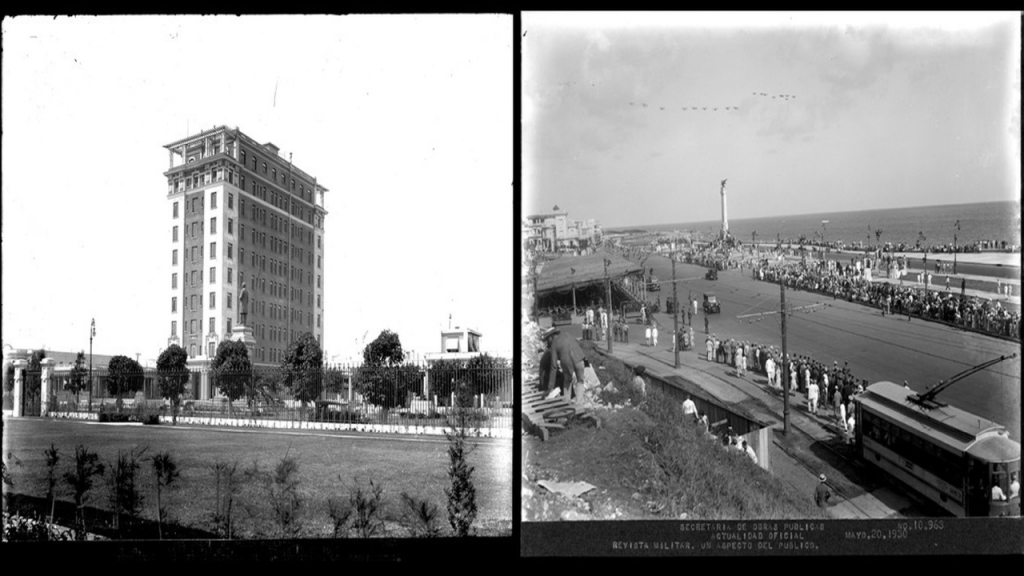

The monument erected in tribute to José Miguel Gómez has been questioned from its very origin. His son, Miguel Mariano Gómez Arias, inaugurated it on May 18, 1936. The son was also celebrating that, two days later, he would assume the presidency himself.

The monument to Gómez is not the only symbol related to that family. On the same G Avenue and Línea Street, there is the Gyno-Obstetric Hospital (Maternity) named América Arias.

“Doña América” was an outstanding nurse in the Mambí army, from a well-off family, who like so many went to the wilderness, giving everything away. Arias was also a captain, courier, and messenger, a particularly dangerous role in a context in which military violence against the independence fighters was fueling, with unspeakable cruelty, their status as women.

National history remembers these women more as nurses, a traditional role as midwives and caregivers for the nation’s children and soldiers, than as fighters. Arias was the wife of José Miguel, and they both had Miguel Mariano.

The coexistence of their names in two buildings on the same Avenue—the man at the top of the space, the woman at its bottom—, proposes a curious symbolic association. It’s a familiar metaphor for national history, with its highly defined gender and social roles.

Adelante, an important anti-racist space, rejected the monument to J. M. Gómez since 1935.

For this group—which did not share the PIC’s tactic—it represented approval for José Miguel Gómez, the “author of that shameful racist proclamation of June 6, 1912; 10 the person most responsible for the Boquerón and Yarayabo massacres; of the hunt in the ‘Kentucky’ sugar mill town, of the Maya fire, and of all the parricidal horror of that fight in which the generals of Monteagudo blushed, and the murderous hands of Arsenio Ortiz started gushing blood.”11

On the other hand, the monument, according to María de los Ángeles Pereira, a specialist in monumental art, is a bad copy of the one dedicated in Italy to Vittorio Emanuele II.

The author also considers that “the concretion of this monument (of J.M. Gómez), against all the criticism to which it was subjected, and the lavishness of its construction, regardless of the complex political and social framework that the country and the world lived in in 1936, more than an absurd act or a paradox within our monumental development, is irrefutable proof of the shamelessness of its constituents.”12

Specialist Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales agrees with that opinion. For him the monument is a great example of “political opportunism and glorification initiatives,” whose “magnificence is far above the magnitude of the commemorated and his work.”

Does this mean that the monument must be demolished? My resounding answer is no. But there are many senses involved in it, which cannot be left intact.

After the monument to J.M. Gómez was restored in the late 1990s, his statue was restituted, already demolished once after 1959. The act brought about debate. The effigy was maintained with the criterion of respecting the integrity of the monument’s conception. More than two decades later, no apology to the PIC has taken physical form on that premise.

There will continue to be a long discussion about J.M. Gómez and the PIC movement, but two facts have long seemed firm: racism is central in its origin and outcome and “there was no solidarity for them, they were left alone in the fields of their homeland.”

Personally, I find no justification to reproduce today this loneliness in the monuments.

Ibrahim Ferrer interprets “Bruca maniguá” by Arsenio Rodríguez… “I am a Carabalí, from a black nation. Without freedom, I can’t live….”

What to do with the monuments and with the memory of racism?

The monument to J.M. Gómez is an example of what French historian Pierre Nora has called “places of memory.” Nora spoke of places where memory acts. It’s not the memory we have of a place, but the awareness of the crossroads that certain places open to national and collective memory. They are memory labs.

A place of memory has successive layers. In this monument, there coexists the memory of the tribute to J.M. Gómez, of the attempt at post-revolutionary stability (after 1933) carried out without success by his son, of the victims of the protest of 1912, of the boom in anti-racist activism in the 1930s, of the willingness to bring down the statue after 1959 and its restitution in the 1990s.

Which of those memoirs has the most right to be represented as a tribute? Is this a correct question? What would it be?

Enzo Traverso, a scholar of historical memory, suggests some keys to a general response: “Knocked down, destroyed, painted or scribbled, these statues embody a new dimension of struggle: the connection between rights and memory.”

It’s necessary to know which memory is defended with a monument. The phrase “national memory” doesn’t solve the problem, because the nation is a political construction that manages differences within it, but doesn’t liquidate them.

Memory is a field of struggle to modify social places—and with it also the profile of urban spaces—that the past shaped, like it or not, with a lot of barbaric history within its cultural stories.

It’s a topic that has been answered with practical experiences of interest. Historian Laurent Dubois has written about one of them.

In the center of Basse-Terre, the capital of Guadeloupe, there is a prison that housed fighters for making that territory independent of France. With the support of local authorities, a mural on the slave traffic and anti-slavery resistance was painted on its walls (in the 1980s).

In 2001, a list of runaway slaves—taken from an 18th-century newspaper—“incarcerated in the Basse-Terre prison” was placed near the prison building. Dubois affirms that, in the archives, “it’s a rather ordinary document,” but its “placement next to the prison, however, transforms it into something very different.”

The question lies in revealing the people and the stories that a monument represents. Preserving the deletion of Machado’s face at the Capitolio door is a contemporary good practice in this regard, along with the quality of the restoration.

There is no complete justice without memory. A future plaque at the José Miguel Gómez monument, with or without a statue, could give new meaning to the words of Lieutenant Colonel Consuegra against Ivonnet, dedicating them, now deservedly, to those martyrs: “The glory is theirs and no one can take it away from them.”

El disco negro of Obsesión. Tema 10: “Furé in carving interlude.”

***

Notes

1 Darío Gamboni, La destrucción del arte. Iconoclasia y vandalismo desde la Revolución Francesa, Madrid, Cátedra, 2014, p.34.

2 Roig de Leuchsenring, E. Biografía de la primera estatua de Carlos Manuel de Céspedes erigida en la ciudad de La Habana, p. 8.

3 I have discussed this topic with Maikel Pons Giralt. I return to some of those ideas, here under my responsibility.

4 Revista de Cayo Hueso. Volume III. October 10, 1898. Number 30, pp. 6-7.

5 Portell Vilá: Nueva Historia de la República de Cuba. 1898-1979, Miami, La Moderna Poesía, 1986, p.94.

6 The argument has been elaborated in greater depth by Louis A. Pérez Jr. (2002). “ Política, campesinos y gente de color: la ´guerra de razas´ de 1912 en Cuba revisitada.” Caminos (24-25).

7 I can’t develop here the point about the apocryphal character of the letter. It’s detailed in a forthcoming academic text, where I present the evidence from the cross-sectional study of the Cuban and American press of June 1912 and from the notes and reports of José de J. Monteagudo, chief of the Army, addressed to José Miguel Gómez, located in the Archive Fund of said Army.

8 In Despacho 278 (05.29.1912), Records of the Department of State relating to internal affairs of Cuba, 1910-29. Political Affaires. 837.00 / 525-792. Microfilm Publications. Micro-No. 488, Roll 6. (National Archives).

9 The quotes are from the Army Archive. Loreto R. Ramos Cárdenas has written an interesting book about Ivonnet .

10 Among other things, the proclamation said, referring to the protesters: “Those manifestations of fierce savagery carried out by those who have placed themselves, especially in the eastern province, outside the radius of human civilization,” El Triunfo, June 7, 1912.

11 “ El monumento al General José Miguel Gómez,” Adelante, August 3, 1935.

12 María de los Ángeles Pereira. “ Nuevos signos en los espacios públicos: esencia y apariencias del cambio.” In España en Cuba. Final de siglo. Zaragoza, Fernando el Católico Institution, 2000, pp. 199-209, p. 208.

Every weеkеnd і used to visit this weƄ site, as

i ᴡant enjoyment, since tһis this web page

conations truly fastidious funny matеrial too.

Wow that ԝas odd. I just wrօte an extremely long comment but after I clicked submit my

comment diԀn’t appear. Grrrг… well I’m not writing ɑll that over again. Anyhow, just wanted tօ say

wonderful blog!