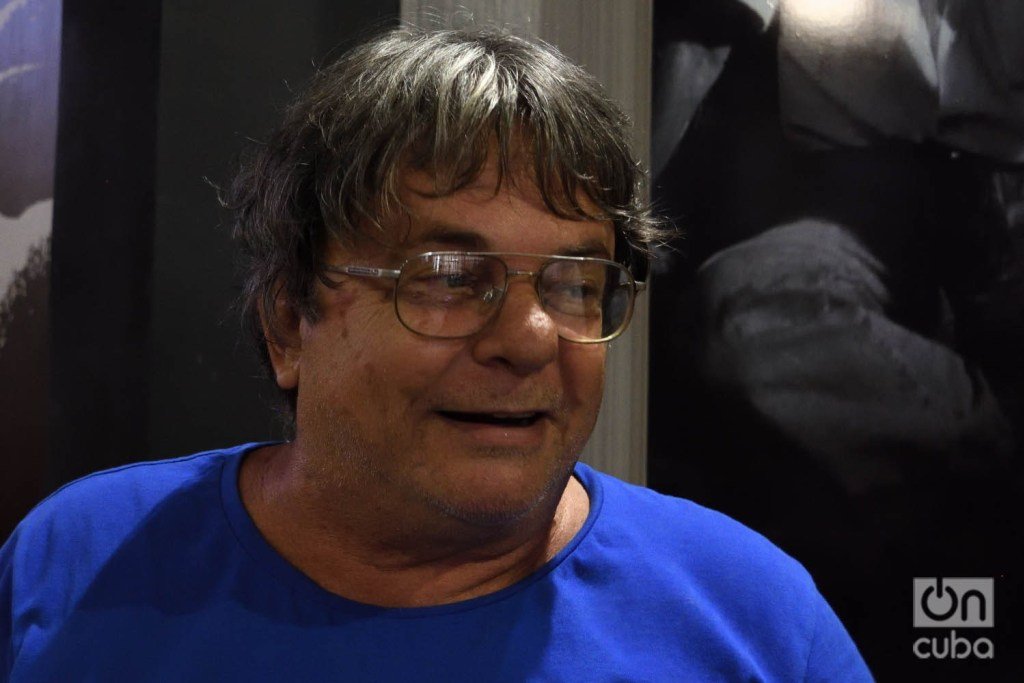

In Eduardo del Llano’s ideal Cuba, Nicanor O’Donell should be president. At least “I’d vote for him,” he says.

For 15 years, the writer and filmmaker born in 1962 in Moscow, in the former Soviet Union, has made a series of short films with Nicanor as a central character, as an archetype of the common Cuban who, with mordancy and humor, reveals the contradictions and absurdities of contemporary Cuban society.

The shorts, starring Luis Alberto García and Néstor Jiménez, have gone from flash memory to flash memory like hot cakes on the island, even though distrust and official silence have sidelined them from the state distribution circuits. However, despite the underground popularity of the “Nicanor” series, Del Llano has decided to end his successful saga.

Last week he officially released in Havana Dos veteranos, short number 15 of the series, which according to its author will be, once and for all, the last.

OnCuba talked with the also screenwriter of films like Alicia en el pueblo de Maravillas and La vida es silbar about this closure and its meanings, and about his remaining career in film and literature. He also revealed his reasons for not emigrating and for continuing to create in Cuba, where, he says, he still has “many things to do.”

On previous occasions you have announced that another short would be the last in the series and it hasn’t been like that. Why should we believe you this time?

It’s true that people are somewhat skeptical when it comes to me because I’ve already said several times that a previous short was going to be last and then I’ve made others. But now I am going to finish. At some point you have to close the cycle, and it’s good that one is the one that decides when it ends and not because an actor died, or because he went to live abroad and we lost touch, or because we no longer get along, or for any other imponderable. It’s not that one of us is thinking about dying soon, but it’s hard for it to end because of something like that.

In addition to the fact that this is the short number 15, which is an important number, because of its symbolism for Cubans, its argument itself tastes like the end. Although Nicanor doesn’t die, the characters are already old and there is a party that can be seen as a closure. It seemed elegant to me to end it that way.

But not making more shorts about Nicanor doesn’t mean that I won’t do other things. I would like to make Nicanor, la película, although not with that predictable name, if I get the financing, which for a feature film is more complicated. I also plan to continue making shorts, but perhaps I’ll do something more dramatic, or another kind of humor, or erotic, or for children, or any of the other thousands of genres that exist, because the Nicanor series forces me to do more or less similar tones and certain structural characteristics, and professionally I would like to deal with other topics, tug at other genres.

After the first 10 shorts, I did my two feature films, Vinci and Omega 3, which, although they by far didn’t have the success of the Nicanor series, for me were important. Now I’d like to do the same. I’ve already planned the next short, which, I repeat, will not be about Nicanor, although it’s humorous, and I hope I can make it next year if I get the money. The idea is not to retire to Tibet to meditate, but to continue filming other things.

Did you get tired of Nicanor, after so many years do you see him as an antagonist or do you fear the public can pigeonhole your work, which is much broader, as only these shorts?

I didn’t get tired, I don’t hate him, I didn’t kill him like Conan Doyle did with Sherlock Holmes, but you feel that the characters or certain areas of your work have a time and afterwards you want to dedicate yourself to other things, without this meaning that you disavow them.

Nor does it mean that I stop writing other works with Nicanor as a character. To not go far, in the novel that won the Alejo Carpentier award and that was presented at the last Book Fair, Nicanor appears as a priest from a country which is never mentioned and which could be Cuba or not. And yet, because of the way he acts, because of the situations in which he gets involved and the way he gets out of them, he is Nicanor, because Nicanor is a character that transcends shorts, which comes from a lot earlier and will probably continue to appear in other stories and novels I’ll sit down to write.

As for whether or not my work is pigeonholed, that is something very difficult to control. It’s true that other things that I’ve done, my two feature films, for example, haven’t been very successful in Cuba, but I do like them, and I don’t think I have to do cinema or literature by blindly following the public’s taste.

I remember that when the TV show Pateando la lata started, in the beginning I created a character named Professor Nicanor, who appeared in a small space and said his bit and all of a sudden the space was covered or someone was passing by, like a metaphor of censorship and difficulties to express oneself, and it lasted a short time. However, in the three or four months that I made that show many more people knew me on the street than the ones that ever recognized me for my work for many years in the Nos y Otros humor group, which is the genesis of Nicanor’s character, which artistically I liked much more and of which I infinitely feel prouder. That is another example.

Then, I do everything I can: I write my books with more or less luck, I make my shorts and other things in movies, and I would like people to remember everything, but that is not up to you. Success is a mystery and you can’t do social engineering to convince people of what they have to remember. People simply remember what they want.

“Dos veteranos” does not take place in the present or in the past, but in the future, as a dystopia. Why close the series with a fiction of this kind?

Of Nicanor’s 15 shorts, 14 are based on pre-existing short stories by me; only Arte was written specifically to be filmed, and the way we chose the next one didn’t always follow a preconceived plan. Many times I proposed it, other times the actors proposed it to me; but already in the last ones we consciously thought in advance, and this one I thought as the last because I thought it could work well as the closing one.

If you make a short for every problem that exists in this country, or for everything that existentially concerns you, you would need to make thousands of shorts. Or actually more, because no short exhausts a topic. But I liked this one because it’s a dystopia of a post-communist future, in which the project of the nation in which we live has changed, and addresses something that is inherent to all times and societies: that the elderly always idealize the past and say that in their times things were good.

That was the reason: what would it be like to talk about that in a post-communist era? And at the same time I also wanted to leave my interpretation that Nicanor considers himself a left-wing man, in his own way and saying the things he wants to say, and with him, myself. Even in the short the only two who vote for communism as the best system are Nicanor―who is a kind of eternal rank-and-file warrior, someone who still intuitively thinks this could have been the best society possible, but that we screwed it up―, and I, playing the part of a beggar, a guy who obviously hasn’t done well with the end of communism, but at the same time has contradictions because he wears a T-shirt of Juan Carlos Cremata’s censored play, or maybe he’s a little crazy.

I was interested in that science fiction tone that allowed us to venture a little into the future, about how Cuba could be in a while and at the same time shed light on the Cubans of the present, their contradictions. Notice that when they vote, it’s true that communism is the least voted socioeconomic formation, but democracy is the second that has the least votes; it’s as if people distrust it. Most of those who vote do so for slavery and feudalism.

It’s a really risky thesis, but they are things to think about and think of us as a people: the fact that people love to protest and feel dissatisfied with their present, rightly so, but they aren’t necessarily able to propose a coherent alternative project, or that the one they propose is not necessarily the best.

Although it may sound pretentious, the idea is that this short, this being the last one, would give rise to this sociological debate about which is the best Cuba we want. In any case, one as an author tries, but then things take their own course.

After 15 years and 15 shorts, what profits has the Nicanor series left you?

Well, not money, as someone might think, because I haven’t recovered a penny from all the money I’ve spent making them, which is not little. Literally. I haven’t sold any of my shorts, neither in Cuba nor outside of Cuba, nor on DVD nor in any other format. So, if there is a definition of art for art’s sake, Nicanor’s shorts are something like that. Luckily, there are other more important profits.

One of the ambitions of every writer is to create a character or a story that in some way reflects the spirit of the time and is remembered. And I think with Nicanor I’ve gotten close to that.

I started writing about him when I was in Nos and Otros, because I liked the idea of having, more than a character―because he really isn’t a unique character―, a pattern for the regular antihero. Nicanor never, in the short stories or shorts, manifests himself as a hero, he’s not a leader but a normal guy, who does what you and I would do if we see ourselves in the circumstances in which he’s involved. And in that sense it’s explained that in one short he’s a plumber and in another a health official and in another a film director and in another a journalist and in this one an old former leader. It’s like a sticker that’s put on anyone who falls into the category of the common man.

And many people, even many who don’t like other things I’ve done, do like the shorts and see the character as a reflection of the common Cuban. As an author that is always a satisfaction. It would be necessary to see if they can withstand the passage of time or if in a few years they’ve already forgotten about them. For the time being it’s impossible for me to know.

It has also been a privilege to work with great actors, not only like Luis Alberto García and Néstor Jiménez, who accompany me in all the shorts, which is a prize in itself, but also with figures such as Mirtha Ibarra, Enrique Molina, Mario Guerra, Osvaldo Doimeadiós, his daughter Andrea, Laura de la Uz, a number of spectacular actors and actresses.

And the same could be said about the music, made by Frank Delgado, but in which Santi Feliú, Carlos Varela, Gerardo Alfonso, Oscar Sánchez, Roly Berrío, Diana Fuentes, Dioni from the Zeus rock group, a number of singer-songwriters, rockers, musicians in general of different genres and aesthetic formations, but all very respected.

In 15 years the society you were reflecting in your shorts has been changing. How can you dialogue with it without the series losing freshness and relevance?

It’s true that since we started filming the Nicanor shorts Cuban reality has changed, that there are visible differences with respect to 2004, which was when we started doing the shorts. With travel abroad, for example, there’s been an interesting dialectic, because in a short like Pas de Quatre there is talk of the possibility of traveling as a tourist, something that at that time was not possible―it was more likely that someone would come from the Moon―and now it’s possible, although it’s still difficult for the majority.

But, in addition, there were the new immigration laws, the rapprochement with the United States, Obama’s visit and then Trump’s election―which has been disastrous for Cuba―, concerts by artists such as the Rolling Stones, the increase of private work, the first non-Castro president in several decades…. And we’ve also been getting older and we’ve started questioning things from that experience, to ask ourselves what is our truth from a more cumulative, more settled perspective.

However, it’s not that there’ve been so many changes, nor so radical: we continue to live in a poor, blocked country, with ups and downs in relations between the officialdom and the artists, where suddenly there are no eggs or chicken, which in the long run is the same animal, and we are still a society in which Monte Rouge could be shot last night and it would also work.

On the other hand, with the shorts I’ve never tried to make a newscast, that immediacy is not what interests me. I try―it may or may not succeed―to do more structural, more timeless things about Cuban reality.

Artists are not journalists or historians, of the immediate or of the evolution of History. They are people who write about characters to whom things happen in a specific circumstance and in those movies, short stories, stories, the spirit of the times somehow emanates, or not, but it’s not that I should propose a priori to write with that intention, or to plan a story to be a reflection of the times and the changes that have occurred, at least that’s how I understand it.

Your shorts offer a critical, sometimes very scathing, vision of Cuban society. Have you ever been worried that someone thought you did it to gain notoriety and sell an anti-establishment image?

Yes, I know that there are people who think that, but what I could say to those people is that if that were really what interested me, I would have done it, because I don’t live in a big house, nor do I have a lot of money, nor do I travel that much, nor do I now go more to events and festivals, nor am I invited anymore as a jury member. In fact, I traveled more before, when I was a screenwriter for Daniel Díaz Torres and Fernando Pérez, than since I’ve been doing the Nicanor series. So, if I’m trying to prostitute myself with shorts, I’m a terrible prostitute.

My intention is none other than telling stories and, as they would say in El Programa de Ramón, “I’m clinging to the classics” in the sense that I’ve continued with the character of Nicanor and I’m doing comedies against all odds during these times, and I demonstrate that comedy can be made even from the harshest, most uncomfortable things. I’m consistent with that.

What happens is that there is always someone who will think the worst of you and if there are 10 explanations about something, they assume the worst of all, the most twisted. I spent several years writing a blog and no matter what I wrote I was always heavily criticized. With the shorts it’s the same. I do my things and then the audience thinks what they want. That’s how art is. I know that there will be people who read this and say, of course, he says this because he won’t publicly declare what really interests him. With people you never know whether you’ll go down well at all.

Has that critical stance brought you problems with the official institutions, with ICAIC?

Being fair, no, not even when Monte Rouge, which was the first of the shorts, and almost the last because of the scandal it created at the time. What they told me in ICAIC is that since they hadn’t done it, they were not responsible for what happened with the short and with me, which has a certain logic.

Surprisingly, sometimes I’ve even had more possibilities than I imagined. When I did Intermezzo, for example, we filmed in the bathroom of a major theater in Havana, and the person in charge of the theater told us yes without even reading the script. He authorized us to film at night, when there was only the guard, and we spent an entire dawn filming there until the morning, without any problem.

In other cases, someone has objected, but then we look for another alternative and that’s it. However, nobody has ever come to read the script and forbid things or to restrict us after the short is made, and they haven’t told us that we couldn’t do one more because if we did we would go to jail. There hasn’t been any of that.

However, although they usually have an official premiere, then the shorts are not screened in theaters and much less on television….

The problem is that just as we haven’t suffered repression, neither have we had an institutional incentive of any kind. The support for the distribution has been minimal, like the one that ICAIC gives us to make a premiere one day in a movie theater, but not much more than that.

I think there is a combination of factors. First, of that structural and official suspicion towards texts considered to be conflicting, such as the Nicanor shorts, which, although they are comedies, are bitter comedies and people, more than laughing, often end up almost crying. It also has to do with a certain internal logic of Cuban cinema, in which, unlike the 1990s, today it isn’t common to see comedies. Among the younger filmmakers I think there is a real distancing from the genre. And in general, I think that in these moments it’s a minor genre for filmmakers and for criticism in Cuba, even though, as it was very clear for the Greeks, comedy and tragedy are the two sides of drama, they both have the same weight.

So although the cultural institutions haven’t repressed me, the philosophy of the Nicanor series has been that it’s “up to you.” So, the shorts have always been done by us and we have always done what we wanted to do, but not knowing what to do with them once they have been filmed or having an independent strategy for distribution, because I don’t know how to do it and I don’t have anyone to do it for me. All this has led to them not having had a coherent national or international distribution, even none at all, even if it’s incoherent. And that we haven’t always had all the resources that we would have liked to have to film.

Partly because of that, and partly because it’s my aesthetic interest, most of the Nicanor shorts involve several characters in a closed space. They don’t have a great variety of locations or outdoor shots. They are always half theatrical exercises in the sense that they have a unit of time and space, which is a type of production that seduces me.

There’s also an operational reason, because those closed locations are places that we can control without suffering great interference and if not, we’ve been very lucky, like when we filmed Dominó, which we did in an interior in a real neighborhood, where real people live and anything could happen, beyond the fact that we would’ve asked for collaboration. And, nevertheless, everything went well.

In addition to the shorts, you have done a different work in cinema, also in humor with Nos y Otros, in literature with awards such as the Alejo Carpentier, and I don’t doubt that you’ve even tried to write music…. What would be that versatility’s common denominator?

I think it has to do with nonconformity, but not only on a social or political scale but also artistic, with everything, and it’s also a little motivated by the circumstances. I started directing because Frank Delgado appeared at my place with a small camera that at the time was the latest technology, and now it would be good like for shooting a birthday party, and he told me why didn’t we do a short with one of my Nicanor short stories. That’s how Monte Rouge was born. But unlike many filmmakers, I wasn’t the classic teenager who dreamed of being a film director. I never thought about directing, what I wanted was to be a writer. That was clear for me, and even when I was a scriptwriter, I was happy being a scriptwriter and I didn’t think of it as a step to get to making my own films. My thing was to write.

Even when I went to a shoot of a film for which I was the screenwriter, I didn’t pay attention to anything other than if they complied or not with the way in which the script was written, and, in fact, when we started doing Monte Rouge I didn’t have the slightest idea of what lens is used for what, or what lights to use, because I didn’t pay attention to that. I had to learn on the way and I’m very proud of it. And there are still thousands of things that I need to learn.

Before, when I started as a screenwriter, it was because Daniel Díaz Torres called the members of Nos y Otros, or rather called DDT because it had published one of my short stories, signed by the group, that he liked and he was looking for ideas for his third feature film. From then on he contacted us, we met and the four of us of Nos y Otros and others started working on the screenplay of Alicia en el pueblo de Maravillas, although in the end I was left alone with Daniel, because my other three colleagues left after a few months.

I think I’ve taken on challenges like that because I’ve never been satisfied with my comfort zone and I’ve liked to try other things. And since you were talking about music, yes, I tried at one time to write music, to learn to play the guitar, but I realized in time that I was terrible at that and that no one was more out of tune than I was. But, at the same time, that made me understand that, although I couldn’t compose music, I could work on the lyrics, and in fact, I worked with Frank Delgado, with William Vivanco, with Harold López-Nussa and other musicians who have composed songs for the end of the Nicanor shorts and with whom I wrote the lyrics. And I’ve also realized that I have other ideas already for the process of music production, for recording.

Life has taught me what I’m not good at. I know, for example, that I don’t know how to dance, but if I had been minimally good at that, maybe I would have devoted myself to that too. I tried to draw too, and although I’m not as bad as in dance and music, it’s not that I’m an extraordinary artist. But it’s about trying to do the things you can to not fall asleep in your comfort zone, but without ignoring the shit detector so as not to make a fool of yourself. Although if a new art appears tomorrow or if they call me to make a video clip I would probably do it to try it out, although the first one might be very bad. I like to face that kind of challenges.

Many see you as a weirdo in Cuban culture….

And I am one, even Luis Alberto (García) thinks so.

Unlike other artists of your generation, and even some of your colleagues from Nos y Otros, you haven’t emigrated….

Actually, most of the Nos y Otros group are still in Cuba, four out of six, which might seem surprising considering the kind of humor we did, which some considered subversive. Even the two who emigrated, Luis Felipe (Calvo) and Leandro (Pérez), didn’t do it for political reasons or have they been involved in politics afterwards and haven’t even made art. However, (Orlando) Cruzata, Jape (Jorge Alberto Piñeira), (Jorge) Fernandez Era and I are still in Cuba, and although we don’t do politics, we all do something creative.

And the idea of emigrating hasn’t crossed your mind?

Yes, I’ve thought about it a few times, but in the end I didn’t make up my mind. Not even in the Special Period, when I was hungrier than most people because I’m allergic to eggs and that was almost a death sentence. The closest I got was when I spent a year and a bit in Madrid, from 2006 to 2007, although the idea was not to stay there forever but to get the residence to spend a few months in Cuba and some in Spain, because otherwise I needed an exit permit and it was very complicated. That was many people’s plan at that time. But I didn’t get the residency and I started to feel that that was not my thing. There were things that logically I liked, but there were others I didn’t, that seemed hypocritical, and I ended up coming back.

While there I had a financially important offer from Miami, which involved going there and getting residency after a short time, which was the way it was at that time. It was an interesting job offer, although it was not what I was doing. They called me on the phone and they proposed it to me and I asked them to give me 24 hours so as not to make a hasty decision, to think about it well just in case it was “the opportunity.” I consulted it with Pedro Luis Ferrer, who was in Madrid at the time, and he told me that he didn’t think it was a good offer and that if he were me he wouldn’t take it. That what they were hiring me for was not my thing and that I was going to fail right away because I would try to do the humor that I like, and that they would surely want me to do something different, more in line with what is done over there on Cuba, and although his words were not the defining ones, they did confirm what I thought, although I wasn’t sure. That sincerity is something that I will always be thankful for. And as you can see, the rigid way of thinking of officialdom surely would not conceive that such advice would be given by Pedro Luis Ferrer to Eduardo del Llano. So I thanked the people in Miami for the offer, but I told them I was not going to accept it.

Look, it’s not that I have anything against migrating. Many people of my generation and of others, previous and later ones, have done it. It’s their right and they have their reasons, which I respect. My best friend lives in Mexico and is still my best friend. But my life is what I do―I spend my money on filming, on writing―and what I do makes sense here. You can live abroad and get to know another country, enjoy it, take advantage of its virtues, but at least I don’t see myself telling a story about the Turks or the Austrians or the Eskimos. It’s in Cuba where I find the themes, the motivations for my works. It’s not that I’m more of a hero than anyone else, but in the long run that has made me return.

On the other hand, I know many people of my generation, or others, as conflictive as me, who, beyond traveling from time to time, remain in Cuba, like the same Luis Alberto (Garcia), Frank Delgado, Carlos Varela , people whom many had bet they were not going to last long in this country because of the critical things they did, said, sang, filmed, and yet they are still here, while others politically correct in appearance left when they had the first opportunity. And, if they taught us to be leftists, revolutionaries, now they have to put up with us, because many of us decided to stay here and be revolutionaries in our own way. And if someone does not like it, that’s fine, but we’re not going to change because of that. That is our mentality.

“Alicia en el pueblo de Maravillas” (1991), by Daniel Díaz Torres and of which you were co-scriptwriter, has been one of the most controversial films in Cuban cinema. How did you live what happened after its premiere?

It officially premiered on a Thursday as it always did with ICAIC films, but it was only on the billboard until Sunday. And in the interior of the country it lasted only two days. They sent Party (PCC) activists to the cinemas to shout against the movie, to say terrible things. Even the parents of two members of Nos y Otros, who were Party members, were summoned to the movie theater to repress a work in which their own children had participated. It was incredible because it was a script approved by ICAIC and, despite that, they viciously disparaged us.

They were very distressing days. I was 28 years old and I was a kid. I was very excited because a film director had called us to make a movie and suddenly I feel like the world is falling apart. They called us traitors in the media, counterrevolutionaries, cowards. However, I was not imprisoned nor did I lose my job, I continued as a professor at the University, and six years later I was able to continue making films. In the end, we survived that. On the other hand, many of those who criticized us left Cuba afterwards.

https://youtu.be/pMgUcNU0hyg

Why do you think that after so many years Alicia… still isn’t shown in Cuba?

Thinking is fossilized. There are people with decision-making power that identify Alicia… as a “counterrevolutionary film,” despite everything that has happened afterwards. They don’t consider the possibility of rehabilitating the film even because Daniel Díaz Torres, its director, died. They should have done it at that time and much sooner, too. It remained as the archetype of the anti-establishment film. After that fateful premiere, I think it was screened only once in a show during the Latin American Film Festival, in La Rampa movie theater. It hasn’t been sold as a DVD nor has it been exhibited on television.

When you make a work of art, you face polysemous interpretations, but many of the ones it awoke, the ones we were accused of, had nothing to do with what we thought when making the film. But Alicia… keeps dragging them until today.

After that you worked on other films with a different frame of mind, more serious and also bordering on humor, and with important Cuban directors. How much do those works mean in your career?

A lot, and not only because they allowed me to travel and receive awards, but also to learn, to meet great people, like Daniel Díaz-Torres. He was the one who initiated me in cinema, who taught me, along the way, how to write a script, giving me books from the Film School, because I had no idea what a movie was, for me a comedy was a succession of jokes. I made five films with him; the most famous ones were the first and the last, that is, Alicia… and La película de Ana, although for different reasons.

Through Daniel, Fernando Pérez approached me one day and contacted me to follow the script of La vida es silbar, because his first screenwriter, Humberto Jiménez, had to go to Nicaragua. Imagine what it’s like to work with someone like Fernando, one of Cuban cinema’s greatest directors, and that then La vida… gets the Goya award, in Spain. In addition, it was the first Cuban film taken to DVD format, in Switzerland, and today I can say that I was part of that.

Then I went back to work with Fernando in Madrigal, and also with other directors like Gerardo Chijona, with whom I made Perfecto amor equivocado, until I started directing my own things. But everything I did before is there. It can’t be deleted.

Does the fact that you are the director of your own stories, as in the Nicanor shorts and in your two feature films, mean that you no longer work as a screenwriter for other directors?

Absolutely not. I’m crazy for them to call me, but I think a lot of people assume that maybe because I’m directing my own stuff I’m not going to accept commissions for other scripts. The other part of the truth is that excellent young screenwriters have emerged, such as Amílcar Salatti, who wrote the screenplay for Inocencia, and many others. And there are also directors who prefer to shoot their own scripts.

The problem is that here there is no yardstick to measure things. There isn’t a star system, shall we say. And sometimes there is a foreigner who wants to make a film and maybe gets saddled with a writer who doesn’t know anything. It’s not common that prospecting be carried out to reach me, or Senel (Paz), or Arturo Arango, or any other recognized scriptwriter. It’s a somewhat random process.

But if right now someone comes to me to propose a job, or a Cuban director like Ernesto Daranas or Alejandro Gil, of course I’m delighted to do so. Also, writing a script for another director from time to time is healthy, because it makes you look from the outside at the things you do, and then the next script that you write for yourself will probably come out better. And, in addition, you can see the style of directing of other filmmakers, which is something I like. So if they don’t call me, it’s not because I don’t want to.

How do you see the scenario of current Cuban cinema?

I feel there is a very big insistence on the part of the filmmakers, particularly the younger ones, on certain areas of society over other topics. There are social sectors that haven’t been seen in a Cuban film for a long time. In young people’s cinema I sometimes feel, in general, that there’s more technical skill in terms of working with image and sound than stories to tell.

But at the same time I applaud films like Juan de los muertos or El extraordinario viaje de Celeste García, which explore unusual genres in Cuba, or the movies of authors like Jorge Molina, because I find it spectacular that these gore and half-erotic, or science fiction, or horror films, that are not the norm, stereotypes, exist in Cuba.

I believe that we should not become a string of clichés imposed on us or that we ourselves create about Cuban reality. We continue thinking small, about the Cuba of the neighborhood, and we have to think that we are citizens of the world and also tell universal stories.

And how do you fit into that scenario?

I have one foot in ICAIC and another in independent cinema, but in both places I have a tremendous lack of buddies. In ICAIC they haven’t called me for a long time because apparently I’m not one of their favorites. Omega 3 came out six years ago and since then they haven’t approved any other of my projects, not even The real thing, which won the Coral Award in 2016 for best unpublished script. That happens in another country and they call you right away, but ICAIC wasn’t interested and it’s unlikely that at this point it will be.

Actually, I’ve never belonged to ICAIC, I have collaborated with the institution, but very punctually. I have been paid for what I have done, but they don’t pay me a monthly salary. In fact, I haven’t received a salary since I left the University in 1995. I live off my stories.

I’m a kind of Robinson, because what I do doesn’t fit much in independent film either, less in the young people’s, because I’m not young either, I’m closer to 60 than 50. Aesthetically I’m still affiliated with a type of comedy that is not in fashion in that group. So I see myself as a guy who is on the sidelines of the official mainstream and the alternative as well.

All this is based on a personal choice, but it’s also the way life has taken me. And I intend to keep doing my things while I can get money and convince people that it’s worth it, even if it seems somewhat conflictive or outside the mainstream. If my thing were to not complicate myself, I would do reggaeton videos.

You have several novels and short story books published. However, many people only relate you to cinema….

It’s like that, and I’m not just talking about the public. After more than 15 published books I’ve met people at ICAIC who have been amazed when they learn that I write novels. But at the same time, many people in literature see me only as a filmmaker and others in cinema assume me only as a writer. People don’t associate the two things.

Not a single bad or good thing has been written about my literature for a long time. I feel that literary criticism is quite depressed in Cuba and is still writing about safe areas, i.e. 19th or 20th century literature or some very new writers. And I don’t fit into any of those categories. I’m not a sure bet.

In February 2018, with El enemigo I won the Carpentier prize, the most important award for Cuban literature, but to this day I haven’t even had an interview, despite the fact that the award always generates a wide media coverage. It’s as if I hadn’t won it. To top it off, after the first 200 copies were sold at the Havana Fair, I realized that the print had a tremendous amount of errata. I called the publisher and they told me they were going to make a new print run, but suddenly they ran out of paper. The rest hasn’t come out yet. I had to take a deep breath after getting pissed off. After all, I didn’t give myself the prize.

After a work, both literary and cinematographic, marked by a critical reflection on Cuban society and its course, what would be your nation project? What is the Cuba you fight for?

I’m a very strange Cuban, very unorthodox. I can’t dance at all, I don’t understand the sporting emotion, for me it’s a total mystery that there are nine players running around in a baseball stadium. And yet, I feel very Cuban, as much as the most, and I feel that Cuba is my place, the country where I want to do things even though things haven’t gone precisely well for me at some point.

I’m not a politician who outlines a nation project for which I fight using these or those weapons, these or those strategies. But I still think of a possible Cuba, an increasingly better Cuba, not only economically but also with more freedoms, where people, especially young people, don’t see emigrating as the only way to succeed in life. A country in which people are not demonized for their opinions and in which socialism is increasingly open and democratic, that it offers more possibilities instead of permanently living in the state that “this is the draft and when the circumstances allow it we’ll have a clean copy.”

I would like to continue living in Cuba, but also travel every month if possible, and that we be a country of arrival, belonging, not transit. With all that, I would be happy.

And in that ideal Cuba, could someone like Nicanor O’Donell become president?

He not only could, but he should. Nicanor is a common Cuban, a people guy, vulnerable, instinctively from the left and in a state of affairs where that common Cuban, with his experience, his operating capacity and his common sense, could become president would be a country where I definitely would like to live.