The FAO (the UN Food and Agriculture Organization) says so: you have to hold onto cassava. But first, you need to sow it and harvest it. And if we get down to business and pull even, this tuber, scientifically called Crantz Manihot esculenta, could become the crop of the 21st century, also for Cuba.

Considered “food for the poor,” its many properties, together with the resilience of the plant, which is planted in infertile and dry lands, and the various industrial uses that can be given to it, confirm the belief that our indigenous people, from the north of Brazil to Mexico, passing through the Antilles, weren’t wrong at all: cassava is a blessing.

Today it constitutes the fourth source of calorie intake for humans, after rice, sugar and corn. Reliable evidence dates back 5,000 years to the beginning of its domestication, and around 500,000,000 people in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania have regularly incorporated it into their diet.

The flour obtained from its roots is an effective substitute for wheat for making breads and sweets. In addition to containing vitamins A, B1, B2 and C, its digestion is faster and its carbohydrates don’t produce glycemic peaks in the blood, something that people with diabetes are especially grateful for.

Currently, the main cassava producers are Nigeria, Thailand, Indonesia, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Ghana. According to the FAO, in 2014 the cassava root harvest on an international scale reached around 270.28 million tons, a figure that could be multiplied several times if the suggestions contained in the “Save to grow” plan, which prescribes the adequate rotation of plantations, preservation of soils with a stable topsoil and little or no use of non-organic fertilizers and pesticides.

An interesting fact is that the Vietnamese are planting the also called manioc with spectacular results. It would not be surprising if, after a few years, that industrious country became one of the world leaders of its exploitation, as it already is in coffee, in which it occupies the second seat as an exporter.

Obviating the benefits of the roots, the other parts of the plant are used, with very good results, in animal feed. In Brazil, from the fermentation of cassava, ethanol is obtained, ethyl alcohol used to replace fossil fuels for motor vehicles.

In the same way that there is no universal panacea, that remedy sought by alchemists to eradicate all diseases, there is also no plant that can potentially effectively combat the scourge of hunger, a complex phenomenon that has its origin in the unequal distribution of wealth.

With proper agronomic practices, cassava can be guaranteed in the markets all year round, something that would come in handy to help shore up the depopulated basic food basket in these times of severe crisis. One more option, not a substitute for other foods that have a preferential place in our culture. That is to say, that although increasing the cultivation of cassava may be a political purpose, the exhortation for its consumption should not become a slogan such as “he who does not eat cassava does not love his homeland” or “if cacique Hatuey ate cassava, why not you?”

In the kitchen

It can be said without shame that, along with corn, cocoa, potatoes, chili peppers and tomatoes, cassava is one of the most valuable contributions of this area of the world to the international culinary book.

But, despite the fact that it is one of the oldest foods in our archipelago, in Cuba it is not among the preferred root vegetables. Its consumption is relegated to Christmas celebrations, such as fritters and boiled with Cuban-style garlic sauce and sour orange. Outside of this scenario, it can be found fried, like pudding and in dense broths like ajiaco, a vernacular version of the Spanish meat and vegetable stew.

Out of 50 Cubans surveyed through social networks, aged between 20 and 60, only five expressed their preference for this root vegetable. In contrast, potatoes and taro obtained 15 votes each, followed by plantain (10). The sweet potato was not singled out once, and the squash had the same number of fans as cassava.

As is known, cassava is one of the few crops that came to be dominated by the Arawaks who settled on the islands that are grouped under the name of Cuba. They grated the tuber to obtain the starch that, after being dried over the fire, served as raw material for the production of casabe, a kind of very thin bread that is still consumed, although to a limited extent, in the eastern part of the country.

With the resurgence of private restaurants, traditional gastronomy has been revived for some time now, and menus are including dishes that if not new, at least have been forgotten for decades, such as empanadas, hoy maize drink and casabe. In the case of the drink, it is an adaptation of the Mexican recipe that is made from corn, a bit more blended than the pudding.

Since cassava consumption is widespread in the Americas, it is easy to detect its presence in regional kitchens. Thus, the Brazilian farofa, the Colombian carimañola, the Costa Rican salteado, the Bolivian chivé, the Ecuadorian white broth, the yucca with Honduran cassava with pork rinds, the Nicaraguan vigorón, the Paraguayan cassava alfajores, the Peruvian cassava with apple sauce, the Puerto Rican cassava timbales, the Venezuelan almidoncitos, and from there on ad nauseam.

The Bobo de la Yuca

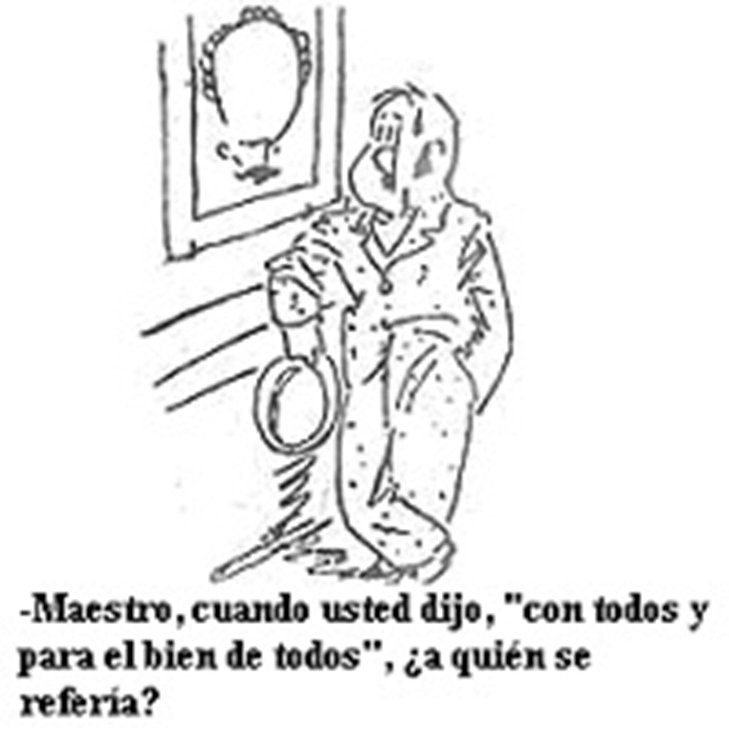

In 1895 the humor magazine El Bobo appeared in Havana. Some of its articles were signed by El Bobo de la Yuca, apparently a folklore character taken up by Eduardo Abela in 1925 as a symbol of ordinary Cubans, who asked cunning questions about the political and economic situation, and slipped scathing and sharp comments, enveloped in a halo of apparent naivety.1

It was Benny Moré who, in 1949, finished installing such an illustrious character in the collective imagination. On that date he recorded the guaracha by Marcos Perdomo that gives the title to the LP “El bobo de la yucca.” According to the number, the aforementioned character wanted to get married, and due to lack of skill and ignorance of the complementary sex, he would spend his honeymoon “comiendo trapo, comiendo papel….”

The Cuban musical repertoire is extensive where cassava, a phallic symbol par excellence, is sung with clever mischief. A quick review brings to our memory some pieces: “Como traigo la yuca,” by Arsenio Rodríguez (also known as “La yuca de Catalina”), “Quimbombó que resbala,” by Lilí Martínez, “El puerquito y la yuca,” by Siro Rodríguez, “La yuca de Casimiro,”2 by Faustino Oramas, “Lucha tu yuca, taíno,” by Ray Fernández and “Yuca y ñame,” by Sindo Garay, a composition recorded by the stellar Rita Montaner.

This last number is based on a popular expression nowadays in disuse, used to refer to situations of extreme economic precariousness. Without going any further, right now the thing is that, “yucca and yam,” but, inexplicably, without one or the other.

***

Notes

- See De Juan, Adelaida. Caricature of the Republic, Havana, 1999.

- “Allí llegaron de Oriente / veinte muchachas preciosas / veinte verdaderas rosas/ que perfuman el ambiente. / Hay una, precisamente/ la hija de Clodomiro, / que al verla lanzó un suspiro/ y dijo de esta manera:/ ‘yo sí que me como entera/ la yuca de Casimiro’.”