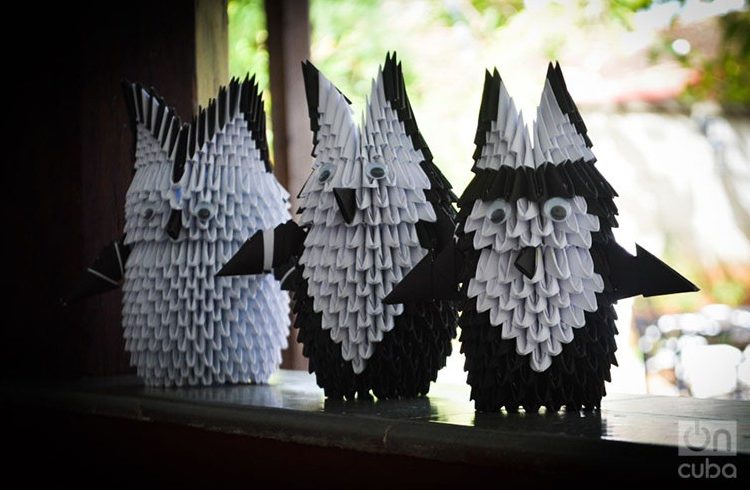

Marcel Gomez Soria is a 13 year old child who carries a shoebox with him wherever he goes to protect his paper creations inside. In his backpack he has a crane, a bunch of flowers, a frog, a cat, a dragon, and a family of owls.

This child from Trinidad is caught in the origami universe, a practice that doesn’t have deep roots in these parts of central south Cuba.

“I like this more than playing baseball, spin tops or marbles,” he says in a low voice while he takes a blank sheet of paper to create a new figure. Marcel isn’t a boy of many words, he prefers to work in order to fight off the nerves and the blinking recorder.

Since the day he showed them the hand-held fan (to combat the heat of the classroom) made from two cables, a battery, the motor of a toy boat and a blade made from an ice-cream pot, his family was aware of the boy’s inventiveness, but no one could have predicted that all of his skills would lead to paper.

“It all started about three years ago when I was sick in a wheelchair,” he remembers. “My mum brought me videos that taught me how to do origami so I could entertain myself. I began to fold the pieces and then put them together: that’s how I made my first swan. It took me two or three hours. I liked it. I did another one, and another one…”

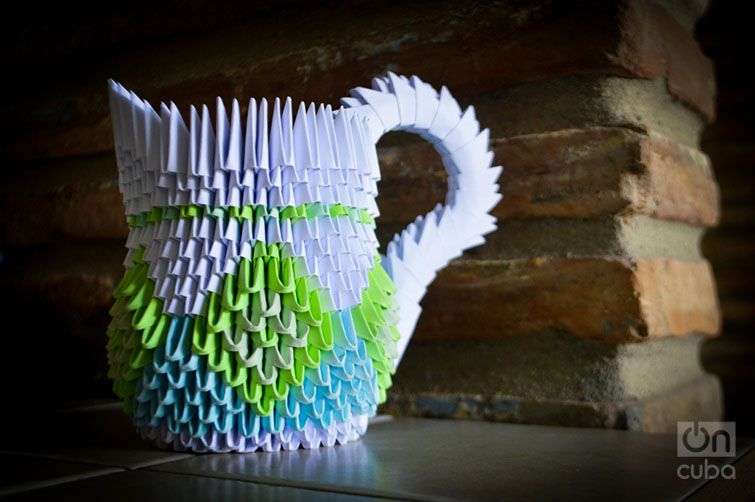

The constant exercise transformed the hobby into an incipient trade. “I learned that there are two types of origami: classical and modular. The first kind you make from a piece of paper, the second is made by connecting pieces together. It looks easy but in the case of modular origami all of the pieces should be the same, you have to know how to put them together and how to combine the colour for the details. Moreover, some animals and objects are really complicated. The most difficult one I’ve done is a swan with two tales. I finished it in the early hours of the morning, it had around 2,000 pieces.”

Months after his discovery, origami and bonsai came together for the first time in Trinidad. Mery Viciedo, a member of the Cuban Craftworkers Association (ACAA) and expert in the millennium-old technique of miniature trees, organised the new craftworkers’ first encounter with region’s artistic circles.

Workshops for children and adults grew out of the initiative, summer courses that had their third round last August, and showcases in and out of the city. Now efforts are focused on a giant expo, organised by Sancti Spíritus’ Japanese club the coming April.

Aside from the fame that’s beginning to surround her son, the thing that mused Maggie Soria Rodríguez the most about the world of Origami is how Marcel has broken down the walls of silence. “He was, and still is, very shy and introverted.

One day he wiped all the videos because he felt useless for not being able to make a figure, but then he took it up again. I think that his biggest merit is that he has learned all by himself, and his ability to make pieces that do not appear in any of the videos that he has, like the jug. We also owe all of this to lots of friends who have sent us paper specific origami paper because in Cuba you basically can’t find any, they give us sheets, pleats, whatever they have, one man from the printers has even given us clippings to use in the summer courses”.

Every now and again creativity can surprise with run-down resources or fatigue after hours and hours of work, but Marcel can’t break the tradition of giving cranes or owls to his friends on their birthdays or a flower to his mum or grandma.

Carlos, this is a wonderful motivational and inspirational story. As Marcel stated, “It all started about three years ago when I was sick in a wheelchair”. This fact connected with me at personal level. It is truly amazing how in the midst of a medical difficulty or hardship, Marcel found his calling and brought to light and forefront, his amazing talents. Thank you for sharing! I will love to meet this family one day when I visit my country, Cuba.