I could never interview Gabriel García Márquez, he hated interviews and never gave me one. I was disappointed. I just talked to him one afternoon a decade ago in Quinta Santa Barbara, home of the Foundation of New Latin American Cinema he presided.

That dialogue resembles an inventory of evasive answers which ended up being advice I will never forget as I venture into the best and worst job in the world as he himself called journalism. Unbearably stubborn and persistent as those who know me know that I am, I decided at that time to rip at least two sentences from the Colombian Nobel, and not leave empty-handed for the office.

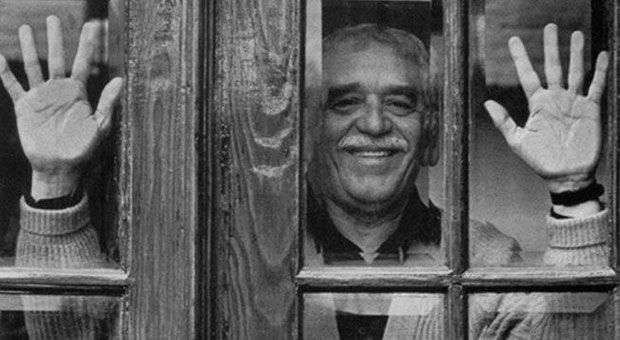

A photo that, like others, a photographer friend of mine never gave me, immortalized the moment that marked a before and after in my view, understanding and interviews.

It turns out that for journalism student who always learned more outside than inside the classroom, all dialogue with one of her literary paradigms, at least the smallest, would inevitably mutated in a master class. Of that I was always certain but I never imagined this conversation would be like this.

I saw him; I was over a presentation I had gone to cover in the context of the Festival of New Latin American Cinema and ran to chase him. I was lucky to find at that time a friend of his, a Cuban filmmaker whom I had met months ago and he introduced me to him for my dream interview would not die before birth.

We started, and my nerves were determined to betray me. I think they noticed. “Pay attention to her Gabo, but if it’s a girl,” Mercedes, his inseparable companion of life told him, who I still thank for her help. He sharply replied that he no longer gave interviews because every day he was bearing them increasingly less because they wanted to make more, and if he spent to answer the questionnaires that reached him from all parts of the planet he would not have time to live.

“It’s nothing personal with you or other journalists, believe me I know how hard it is to do that job that gave me many years what to eat, but understand me, already the questionnaire responses are like reading fiction and create pages that are always equal and I must invent a new story about the same each time. I no longer have evidential value so they become small novels that I recite to the wind, “he said.

“I always compare interviews with love, one lives waiting for the interviewer of his life, as happens with romantic relationships, and I’m ready not to wait any longer,” he added.

Does it bother you if I record this?, With great respect I made the mistake of asking because I did not forget a single word of those reflections. He gave me a resounding yes that paralyzed me and taught me that the recorder was an invention that had atrophied the sense of reporters because it didn’t record the heartbeat and then the reporter became too trustful and lost the sensitivity to the answers. “If you want to be someday a good interviewer, do not record, do not get used to entrust the devise, hear the interviewee, and understand him.” He advised.“

Another mistake: I came to ask for his masterpiece One Hundred Years of Solitude and he replied tersely that he no longer stand it. I was expecting any answer but that ine. He left me puzzled and I managed to ask him why he had been in love with Cuba?

“‘There are so many reasons and I have not the time now that I ask you to look around yourself and find the answer on everything I love about this country,” he said.

I remember it like it was today, and I remind myself looking around to the puzzle he raised.

He said he learned only after forty, to say no when it is not and that he would not answer me anything else that I apologized and he thanked me politely.

Likewise I thanked him and said goodbye. He then told me what I will never forget and gave me back the breath he had taken from between question and answer.

You know why I kept talking to you? He asked me, and I did not know what to answer. “Because you’re persistent and do not you give up and it’s something I always admired on Oriana Fallaci, who at moments you reminded of by not go running nervous on the account of so few yes I have given you.”

I left laughing, something frantic and upset, but happy inside and out but without a line to deliver the newspaper. Whenever I feel sad with my profession, I remember that day and I thank life for that experience with Gabo.

Of that dialogue that he made me tattooed on my memory I did not published anything, I do not think they would have accepted it that afternoon, I kept it for me and today I share with you in honor of the Latin American writer probably most loved and read of all times.

They say he died, for some it is the last sentence of a chronicle of death foretold that he wrote his first letter the day he was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. Those who read him and still do, we always have him there for us, to advise and inspire us with his magical realism and precise words in this art of urgent letters he lifted so high.