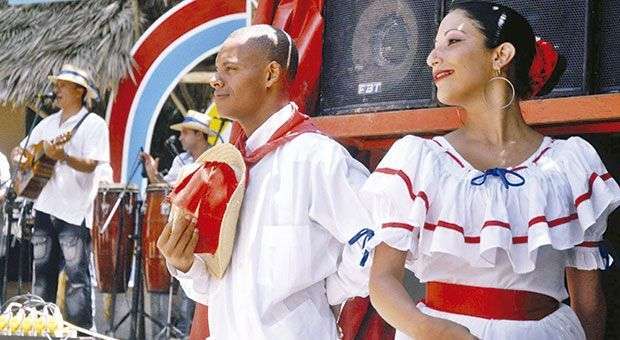

Dusk in Havana. The family has been assembled. One or another coffee cup has yet to be taken to the kitchen; neighbors’ voices compete with the television, which is on. The grandmother and the cousin visiting from out of town are enthusiastically watching the program Palmas y Cañas. The rest of the family pays attention only sporadically, on the fence between accepting the program as their own and disassociating themselves to uphold their status as urbanites.

The longtime program has played a beautiful role, but those of us who love the music known as “punto guajiro,” and especially the formidable art of controversias, or poetic duels using the sung décima (rhyming verse), it is just a reflection of a rich world with a long tradition.

The custom of joining in a canturía (group song) or guateque (rural fiesta) to improvise décimas came to us from Spain. Vicente Espinel is the man credited with forming the stanza as it is today, and researchers say that it is one of many legacies from our Canary Island ancestors. One of the founders of this living tradition defined the décima as a Spanish traveler who put down roots in Cuban land.

It is an artistic creation that continues the ancient tradition of oral literature. We tend to forget that the written word is a recent phenomenon. The type of punto—espirituano (two voices, fixed meter), libre (no fixed meter), or cruzado (syncopation alternating with a stable rhythm)—is important. So is the charm of the improviser’s melody. But the real enchantment of a good controversia is, above all, literary inventiveness. On the fly, its creator composes 10 octosyllables in rich, complicated rhyme. The fourth verse’s pause is a musical opportunity, a few seconds for the poet to think and continue his or her undertaking in front of an expert audience that will applaud him or her in a resounding—and sometimes especially fortunate—finale, when the poet embarks on the final attack at the decisive moment: the “bridge” between the two quatrains, between the sixth and seventh verses.

One culminating moment of the fiesta between singers and followers is the “pie forzado”; the final verse is launched and that is how the poet must end his or her creation composed on the spot and in front of everyone.

To learn more about the history of the sung décima and the details of its physiognomy, one can read the books of the scholar María Teresa Linares. And for a lovely audiovisual summary, the documentary by Octavio Cortázar, Hablando del punto cubano (Talking about the “punto cubano”).

The popularity of these improvising poets goes back to the early 1940s. At that time, Joseíto Fernández would narrate the day’s events with a piece of music that gained the name of Guantanamera. Before Pete Seeger gave it its universal, epic character, Fernández, a popular singer, used the melody for years for more immediate, domestic affairs.

Many are the names of those to whom the décima owes its fame. These include Naborí, the singer, and an elegant poet in writing; Justo Vega, one of the founders, and, together with Adolfo Alfonso, a real legend on the best of the evening Palmas y Cañas shows.

In the last two decades, one of the essential names has been Alexis Díaz-Pimienta. His book, Teoría de la improvisación (Theory of improvisation), contains both detailed research and the practice of the poet himself, who has been interlacing rhymes since childhood. Alexis was one of the first to break with the notion that the sung décima is an art exclusive to rural folk. In one celebrated controversia, his opponent was singing to the River Mayabeque, and Alexis highlighted his status as a guy from a Havana neighborhood: “Pero el Mayabeque mío/ es una zanja del Diezmero/ que ni yo porque la quiero/ me atrevo a llamarla río”. (“But Mayabeque my beloved / is a ditch in Diezmero / and even I who love it so / a river wouldn’t call it.”)