On days of social distancing, where relationships are happening remotely, games and challenges are flourishing on social media. All the avalanche of #challenges makes me wonder: Do we know what’s the human challenge with regards to nature after this pandemic is over?

This world on pause has made the Himalayas visible from Punjab in India; wild animals rediscover semi-deserted cities; air quality is exponentially improving in some areas, and many of us are comforted by the idea that the environment is benefiting from this temporary break.

Will this impact have a lasting effect on the environment? Will we accept the #challenge of creating a new reality that seeks balance with nature after coronavirus is over?

Current context impact on the environment. How to read it?

In the presence of so much social change regarding our mobility, politics, markets and the economy, it is not rare to wonder what’s its effect on nature.

The new wildlife behavior of day walks through empty cosmopolitan cities, and the temporary reduction of our consumption levels do not represent the change that we need. But, they could be the preview of a movie, or new television series, narrated by Mr. David Attenborough, which might as well be named: “Nature. An opportunity to recover ”.

In order to understand the impact of the current context over nature, let’s review some of the main issues that intervene in the subject.

- Air quality

- Greenhouse gases emissions

- Agriculture

- Politics

- Air Quality

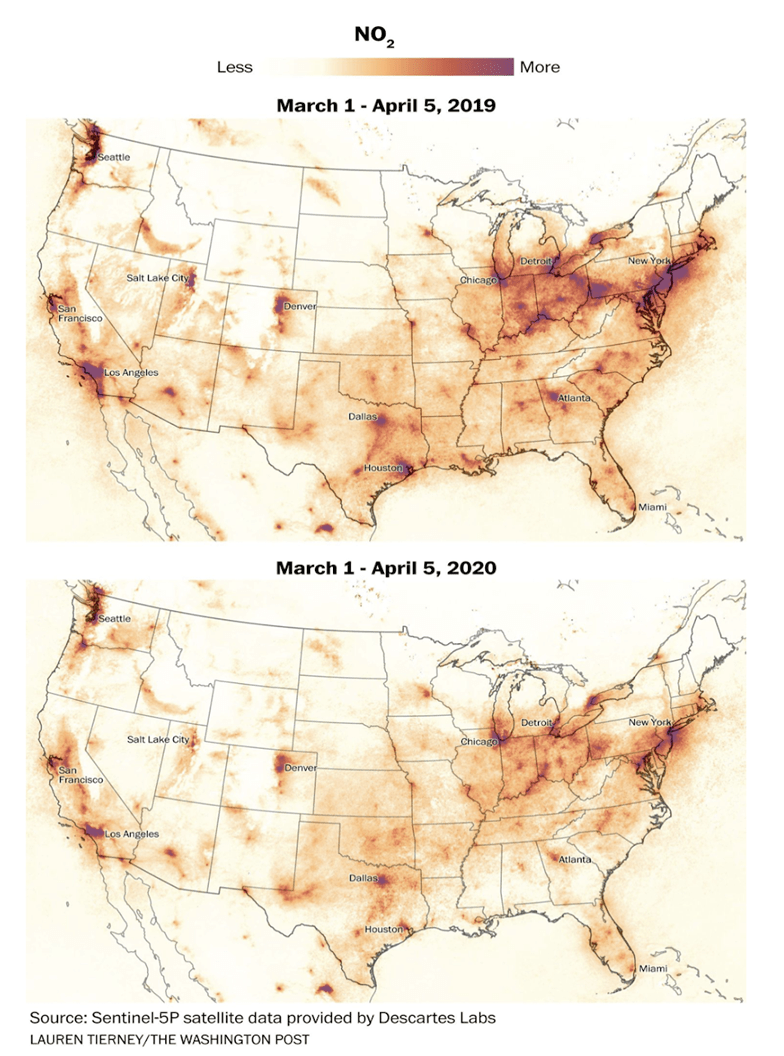

We might all have already seen some comparative image of gas emissions that influence air quality with respect to previous years, or we might have even read that some people call this moment as the temporary hiccup of emissions.

Many of the most polluting cities in the world are the ones that have the strongest measures against the coronavirus. They are putting factories on hiatus, reducing flights, minimizing the mobility of cars, and in some way reducing their consumption and pollution levels.

Unintentionally, this context created a sudden change in air quality, an index that the World Health Organization (WHO) associates to 7 million deaths each year. For example: there is a 30% change on this indicator in Los Angeles, CA. which means that instead of having “moderate” air quality, they can enjoy “good” air quality for now.

The WHO also declares that 9 out of 10 people in the world breathe polluted air; so it is likely that you and I are among those 9. That’s how close we are to this issue – a Sustainable Development Goal that makes so few media headlines per year.

A Harvard study recently described how COVID-19 mortality is linked to people’s exposure to polluted air. The result shows the relationship of the coronavirus with the average long-term exposure to fine particles in the air (PM2.5), highlighting the importance of continuing to strengthen regulations with regards to air pollution in order to protect human health during and after this crisis. In conclusion, the research points out that “a small increase in long-term PM2.5 exposure, leads to a large increase in the death rate” regarding the pandemic.

As air quality improves, we are less vulnerable to this pandemic and to other diseases.

With this temporary lifestyle, we have seen a drastic pollution drop in some places. The Himalayas can now be spotted from India, the skies are bluer than usual, and many people can enjoy living with less pollution. But, if we do not change our consumption patterns, all those improvements are expected to disappear as fast as they arrived.

- Greenhouse gas emissions

Among the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions we can mention agriculture, transportation, industries (including constructions, which is one of the most polluting), electricity generation, etc.

Sectors like transportation have been affected, reducing the volume of international flights, the volume of car sales, etc. We have also seen some data regarding reductions of these gasses’ emissions that is encouraging. For example, China reduced its CO2 emissions by 25% over a short period of time, compared to the previous year’s emissions. But the environmental community remains skeptical about those improvements. It would be naive to think that a temporary hiccup in the lifestyle of the most consuming countries could make a substantial change.

Besides, most of those environmental changes could be easily reversed after the pandemic, when countries might try to return to “normal”. As seen before, in an economic recovery effort, countries might increase their emissions even more than expected during normal times.

How is the impact for Europe?

Forbes quoted recently an article by the Independent Commodity Intelligence Service that highlights the main results and projections on evaluating the effect in that region.

The article projects “a 10 percent drop in power demand across Europe from March to June, then a steady recovery by the end of 2020”. They assume “a 50 percent drop in industrial production from April to June, then a year-long return to full production”. It also anticipates “a 7.5 percent drop in airline emissions for the first quarter, then an 80 percent drop for the following two—because of a restricted travel schedule—followed by full recovery.”

Most of those emissions are directly related to CO2, but that is not the only greenhouse gas in play. The main pollutant industries also include the emission of methane, nitrous oxide and other gases. But how much of these gases will be temporarily reduced is not the most relevant fact for environmentalists. The projection of what is likely to happen in subsequent months is the main concern.

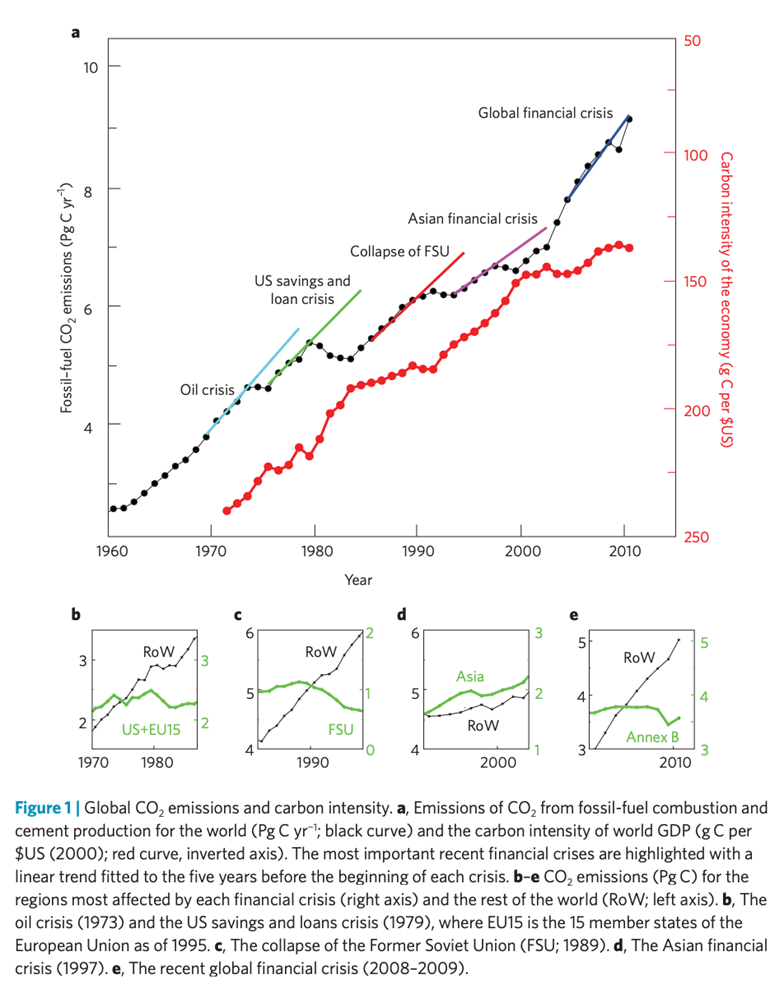

Emission reductions from economic recessions tend to be temporary and can lead to an increase in subsequent emissions as economies make an effort to recover. An example of this was the financial crisis of 2008, where emissions grew up to 5.9%, basically due to the increase in the use of fossil fuels and the production of cement in the recovery efforts after the crisis.

Our hope is that this trial period of the world in pause serves to put some of our values in place and shake our priorities ladder. The development of a new world order, in balance with nature, does not depend on the short-term measures that are a consequence of the pandemic, but on the political decisions and long-term will of each country.

- Agriculture

Deforestation – mostly the one that occurs for animal agriculture purposes – is one of the major causes of habitat loss, which forces animal species to migrate, generating impacts on them, and on us. This is one of the ways agriculture relates to the coronavirus.

Intensive animal agriculture per se also serves as a source of pollution and infection from animals to people, with a long list of negative effects on our health. That is why the vegan philosophy has been gaining so much popularity in recent years, since this culture isn’t just about animal justice, but also about human preservation, by encouraging the minimization of the animal agriculture impacts.

In the environment everything is connected, although sometimes we might not see it, or understand it.

One of our current challenges is how to maintain stable food production for the existing demand. This is a good time to highlight the trillion food produced that is wasted annually, according to FAO. All the food wasted in a year represents a third of the world’s food. Reversing this trend would represent enough food to feed 2 billion people. – For the reference: that number of people represents more than double of the malnourished population in the world today -.

Regarding the relation between coronavirus, agriculture and environment, it seems obvious that a sustainable and responsible agriculture will make us resilient to emergencies like the current one, including the impact on human life and our environment.

We would need to rethink the philosophies, modes of production and consumption. For the industry, it would be by minimizing the impact of the intensive agriculture philosophy; by developing organic and sustainable practices. For consumers, it will mean by responsibly demanding and consuming products backed on responsible practices. Agriculture will also depend on the political will of each country, something in which we all have power and responsibility.

- Politics

What’s the impact of human presence?

Having empty cities has given deer, birds, goats, and other animals the confidence to reconquer places where they once lived. It almost seems like a protest of those who try to regain their space. Although noise pollution is not highly debated, I’m sure it has also decreased in this period, avoiding disorienting species or changing their usual behavior. That is why we can watch so many funny news from herds of animals that seem to replace us in the city; and I can enjoy hearing birds that I had not seen or heard before from my balcony.

Environmental conservation and balance with nature is a major concern for many people in the world. The climate strikes that have been going on for more than a year every Friday are now online. Although many young people continue to participate, the political impact is less. And with the ongoing crisis and other priorities, politics does not favor environmental issues.

But how does governance influence our vulnerability to zoonoses?

Laws play a key role in reducing the chances of another disease spread like COVID-19. Our safety relies in part on the regulations for places where animals and meats are marketed.

Human lifestyle also influences our vulnerability to these pathogens of zoonotic origin. Zoonoses are diseases that exist in other animals and get to infect humans.

The adaptability of viruses to change hosts and mutate under new conditions, together with our cosmopolitan lifestyle, living in conglomerated cities, and traveling from one place to another, make us highly vulnerable.

Those who explain how the coronavirus reached the human being, include as part of their argument: the displacement of species, the disproportionate use of antibiotics, and the deregulations regarding dealing with animals.

With the COVID-19 story, bats stand out as big carriers of viruses. This happens because they have great diversity within the species, allowing each one to have different viruses. Furthermore, they have a relatively long life, and live together in large communities – something that makes them infect each other very easily -.

Human behaviour has destroyed habitats, which causes animals to approach our spaces in search for food. That way, it is also easier to spread animal diseases to us.

Some theories about how COVID-19 got to us indicate that the bat did not directly pass the virus on to humans. The coronavirus could have mutated to another species like pangolins, and from there, to live inside us.

Due to those theories, Media has sometimes demonized bats, which are necessary for the balance of ecosystems, helping control harmful insects, pollinating flowers and helping with seed dispersal. Asian cultures have also been demonized in many cases, because the virus originated in China.

But the matter is not about countries, or cultures. It is about regulatory policies, and about the way we interact with wildlife, in order to minimize our exposure to zoonoses. It is important to remember that the H1N1 virus has swine origin, and pigs are common animals throughout the world.

Deregulations and flexibility for highly polluting companies have also appeared because of the current economic vulnerability. For example, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a temporary deregulation (without providing limits on that temporality) under which they basically state they will be suspending or flexibilizing the enforcement of environmental laws.

The issue of the EPA suspension explains the enforcement discretion outlined in this temporary policy, stating that as a consequence of the pandemic, laboratory analysis operations and facility reporting obligations may be affected. These impacts may include the ability to perform operations that meet the stated regulations to discharge emissions through water and air.

In other words, this temporary policy tells companies that they can contaminate or violate environmental regulations for now, as long as they declare that these environmental violations are related in some way to COVID-19.

Other countries also face deregulation spaces that have a negative effect on the environment. Those types of policies are focused on defending human life in a moment of force majeure. But if environmental regulations are supposed to exist to protect us, how are we going to remove them in a moment like this? Is the deterioration of the environment, and its consequences on us, not a force majeure?

Many people wonder about the relation between the coronavirus and climate change. Although some say there is no direct evidence, we know that part of the impacts of this phenomenon includes the connection of species on earth, which directly affects our health, and increases our risk of infection.

As the planet warms up, animal species move and adapt their behavior in search of favorable conditions for them. This implies that there are new contacts between species, which offers an opportunity for pathogens to stay in new hosts.

If we do not see environmental protection as a major cause, we will continue to increase our vulnerability as a species to new phenomena that may put us in danger, such as the coronavirus.

Earth Day, April 22, is a date to rethink and support environmental protection. This year, the celebration is mostly from home, as if the planet had grounded us, sending everyone to their room, in order to make us reflect on our current lifestyle.

This time, on the 50th anniversary of earth day, we celebrate it by rethinking how to return to a new “normal” in search of a balance with nature. Especially now that we have shaken up our priorities, and the mind is open to new ideas.

The invitation is to re-approach consumption in a responsible way, to believe in individual power and influence country policies, and to act accordingly with what we are: one of the many species that coexist on the planet.

The #challenge regarding nature is in our mind.

If we change the way we see the world as societies, we might use natural resources with the same vision of balance that nature is teaching us.

Ultimately, we will have to learn from this obligatory break that COVID-19 has imposed on us, and take from it the best lesson we can, in order to live a new and more secure future.