Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez was 38 years old when he flew into outer space. I was not yet four. By then, Tamayo had already been in the process of selection and arduous preparation for the joint Soviet-Cuban flight of the Soyuz 38 for nearly three years. During that time, I had learned things that were very important to anyone, such as talking, walking and not peeing in my pants, which, however, cannot be remotely compared to flying to the Saliut 6 orbital station alongside Soviet Yuri Romanenko to spend more than a week in space and go around the Earth’s orbit 128 times.

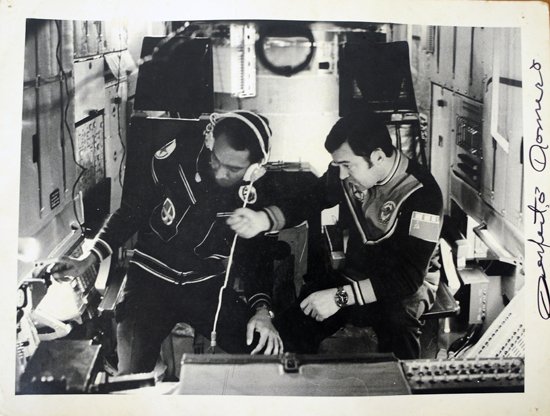

On September 18, 1980, 40 years ago, at 10:11 p.m. Moscow time, 3:11 p.m. Cuban time, Tamayo and Romanenko took off from the Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. The Cuban was traveling as a research cosmonaut; the Soviet―who had already flown to the Saliut space station in 1977, to spend more than three months and even do a spacewalk―as commander of the spacecraft. Leonid Popov and Valeri Riumin were also waiting for them at the orbital station.

I don’t know if it was that night or one of the next six that my father carried me to the balcony to show me the starry sky. The Cuban cosmonaut was up there, thousands of kilometers from my native Camagüey, somewhere lost between the blackness and the late reflection of the stars, and the whole country celebrated it as if it were the decisive victory over imperialism. My father, who had just returned from Bulgaria, from where he had brought me, among other things, some huge towels with the smiling image of the little bear Misha―the Moscow 1980 Olympics mascot―told me something about outer space and pointed to the night sky.

This is one of the first memories I have of my childhood. I, in my father’s arms; him, showing me the night sky, without being able to distinguish exactly what he was pointing for me. Or perhaps he was not pointing out anything, he was just making me notice the immensity of the universe in which that intrepid Cuban, black and eastern Cuban pilot had immersed himself for more signs, and then, over the years, I added to his gesture the meanings I never had and for which I never got to ask him.

Tamayo and Romanenko’s flight, which was part of the Intercosmos program promoted by the former socialist power, would last 159 hours, 49 minutes and nine seconds. While they were on Saliut 6 they moved at just over 28,000 kilometers per hour, about eight kilometers per second, taking an hour and a half to bypass the planet. The Cuban, according to himself, did not have a very good time at first and took three days to adjust to the weightlessness. However, he was able to recover and participated in a score of experiments and research tasks, most of them proposed by Cuban scientists. Finally, he returned to Earth on the 26th with Romanenko, and both were received as heroes and decorated in Cuba and the Soviet Union.

By then, I was far from knowing what the Cold War and the Space Race were, or how the socialist propaganda worked, which quickly, even before the historic flight, multiplied Tamayo’s face and name throughout Cuba, and turned his feat into children’s songs and contests. The dark-skinned, Guantánamo-born cosmonaut, son of a humble family, who had made a career in the Cuban air force until reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel, was praised as an example of the greatness of Socialism, that there were no limits for human beings in our luminous social system. Going to outer space, after all, was not impossible for those born on the island.

I grew up, like the rest of my generation, with that image. The dream of flying into space, of discovering the mysteries of the universe, of wearing a spacesuit and contemplating the Earth from the hatch of a spacecraft, encouraged us all at some point. It didn’t matter that in our fantasies science fiction films were mixed with instructive publications that arrived many times from the Soviet Union itself, the battles in Star Wars and Japanese animes with school reading notebooks that glorified the conquest of outer space. In our stellar pantheon, along with Luke Skywalker and Voltus V, was―perhaps not at the same height, but he was there―Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez.

The illusion would gradually dissipate. The 1980s would pass without any other compatriot following in Tamayo’s footsteps. Nor did he return to space, as did his partner Romanenko, who in 1987 spent almost a year on the Mir orbital station and definitively inscribed his name among the legends of cosmonautics. Personally, I found that short-sighted as I was, I couldn’t fly even an escape module, even if I still fantasized about robot explorers and lightsabers. My father would return to Bulgaria and upon his final return to Cuba he would end up divorcing my mother. The cosmos was never a topic of our many conversations since then.

However, I kept thinking that before 2000 a lot could happen. And it was so, although not exactly as I imagined. Among them, the collapse of the socialist camp, the arrival of the Special Period and the death of my father.

In the 1990s, with the constant power cuts and the demise of the Soviet Union, the cosmos became much more distant than it already was. At least for the Cubans. Getting on a spacecraft and looking at the Earth from up there definitely became a utopia. In an illusory and meaningless mission in the midst of so many shortcomings, so many earthly needs. Those of my generation barely talked about Tamayo, even when his face appeared from time to time in the newspapers and newscasts, and when we did, the―unfairly―ridicule, typical of that national taste for making jokes, surfaced not infrequently, laughing at even the most sacred things. (I remember a recurring joke from senior high, according to which the Cuban had returned from space with his hands swollen, due to the slaps that Romanenko gave him when he tried to touch something on the ship.)

Another 20 years have passed since 2000. Cuba is certainly no longer the same as two decades or, much less, four decades ago, although in some ways it still resembles it. Neither is the world. The Soviet Union does not exist and its heir, Russia, although it maintains an active space program and has strengthened ties with the island, has not invited any Cubans to return to space. The United States leads the space race and a Cuban-American, astronaut and NASA surgeon Serena M. Auñón―who like I was three years old when Tamayo Méndez flew in the Soyuz 38―went into space in 2018 taking some black beans prepared by her family.

However, beyond the jokes and time, Tamayo’s feat has not been dwarfed. Conversely. Even though many others have flown from our planet since then, today’s Cuban Brigadier General continues to be a pioneer: the first Latin American, Spanish-speaking and Afro-descendant to do so. Not because of a photo or a political campaign, but because of the events that build posterity. That merit, such as having been among the first hundred men to travel to outer space―and placing Cuba as the ninth country to send one of its own into space―will forever accompany his name.

At 78, Tamayo keeps that flight fresh in his memories as if it had happened yesterday. And I, as I suppose many other Cubans will, too. So 40 years ago, I had no idea what was happening, why my father would carry me to the balcony to show me the starry sky. But that night would be permanently etched in my memory and would forever give the Cuban cosmonaut a special place in my affections. Even if I don’t know him personally. Even though his trip also had a political and propaganda sense. Four decades ago he was up there with Romanenko, and I was down here in my father’s arms. And that’s enough so that, even as the years go by, he continues to be in my stellar pantheon, along with Luke Skywalker and Voltus V.