If the journalism students of my generation had been told that Gay Talese, the author of Honor Thy Father (1971) and dozens of iconic stories of New Journalism such as “Mr. Bad News,” walked the boiling streets of Havana camouflaged in that daily life of survivals, the entourage that he would have achieved was going to be extensive, like that of his last visit, when the island was emerging from a crisis accentuated by the fall of the socialist camp and the strained relations with the United States. “It was one of the most exciting experiences of my writer’s career,” the 88-year-old teacher assures me.

I’ve broken one of his golden rules. “I don’t interview by email, I’ve always thought that people have to be seen face to face,” he once said, and now confirms it with me: “What I do, and have always done, is to be physically present, without telephone interviews, without Zoom; no email exchanges, if I can help it.”

But, even following his precepts to the letter, I have no choice but to take advantage of a few questions and his accumulated prose. From the 8,500 kilometers to the south that separate me from the famous five-story brownstone where he lives in Midtown New York, and with an email address at hand, certain advice cannot be obeyed; not even when they come from the notebook with the golden rules of New Journalism, written by one of the greatest of all time. There’s no choice but to dive into the past, in whatever way.

It’s mid-morning on January 18, 1996. Holding his luggage in his left hand, Gay Talese descends the steps of the plane that has returned him to José Martí International Airport. The aircraft arrives from Miami as a hopeful flying symbol. Muhammad Ali, the legendary heavyweight champion, is the main figure on board, the publicity face for a medical donation promoted by two American humanitarian organizations.

Talese does not lose sight of “the greatest.” He needs details to later download them to the readers of The Nation. He watches the still massive 54-year-old ex-boxer, followed by his fourth wife, Lonnie Williams, and his biographer and friend, photographer Howard Bingham, descend on the tarmac of the track, where he will be hugged by his host. Teófilo Stevenson embraces him discreetly with his long arms, like those of a flexible crab.

They exchange friendly and brief greetings. Ali seems self-controlled. His face remains expressionless, even though it shows an outline of a discreet smile. His eyes are hidden behind dark glasses, his hands are shaking. Talese takes the opportunity to take a panoramic view: groups of journalists huddle together, potential officials watch. Nobody wears olive green. The visit does not have a directly political objective, although there is politics even in the drinks that will be missing in the cocktail party at the Palace of the Revolution.

The soles of his shoes connect with the asphalt. He responds to those greeting him and suddenly discovers that the famous former heavyweight champion has been taken to the transport, on which they would all roll off the track, to begin a five-day journey.

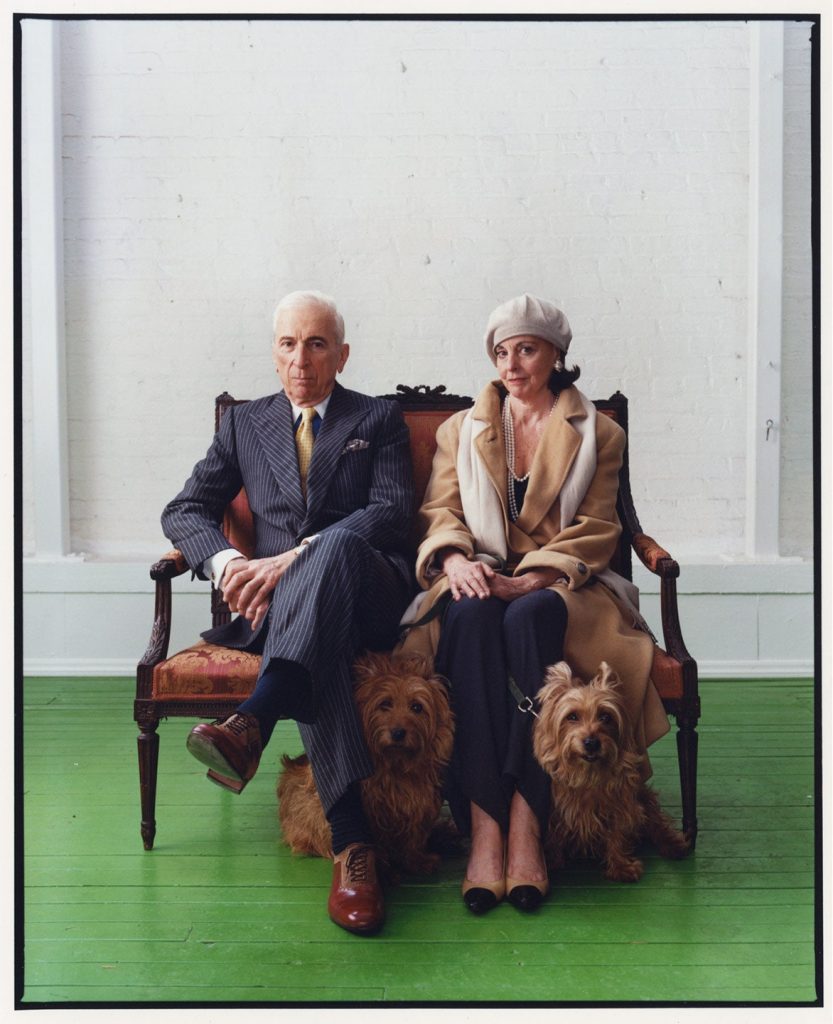

Havana may have seemed similar to the one he knew, but it has suffered a harsh circumstance. Five years have passed since the dissolution of the Soviet Union and not even the hotels serve the Bulgarian wines he got when, together with his wife, the editor of Random House Nan Talese, he lived for two weeks in the Habana Libre Hotel, in 1981. Now the economy has contracted. So many cracks have been opened in the dream of the Revolution that it resembles a dry cake about to be destroyed. All in all, the island’s government is overcoming a five-year period of desolation and, what is even more unusual, the leader of the Revolution, a man who is about to turn 70, is optimistic in each of his long appearances.

Although it is not the focus of his visit, these are the stories that have interested Talese since he appeared in journalism as a passionate fan of Frank Yerby, John O’Hara and the New York Yankees. He is obsessed with circumstances and characters who persevere in their aspirations; like that other two-time heavyweight champion, Floy Paterson, whom he wrote about so many times during his years as a sportswriter for The New York Times and whom he described in his book My Writer’s Life (2006) as a man who never quit and always tried to get up, even in moments of disappointment and defeat.

Paterson hurried his retirement at the age of 37, after a KO by Ali, the character about whom Talese now writes and who has not been removed from the scene by the Parkinson’s he suffers. Neither did the United States do away with Fidel Castro or those in Cuba who think like him. “The United States has tried to meddle in Cuban affairs for decades and decades,” he says: “I’m glad they didn’t succeed. The Bay of Pigs adventure was a disaster for John Kennedy. He was a charming man, but arrogant, possibly because he grew up privileged and rich.”

Inside a monumental building, in the old part of the city, Ali delivers the donation. He himself has contributed half a million dollars and the Cubans thank him. Talese slips among the colleagues, his body, just like that of a fencer, manages to put him in the right place to listen to Stevenson, one of the best in amateur boxing and three times Olympic champion, who welcomes his colleague, now for the cameras of dozens of press agencies and television channels.

Still smiling, perhaps because of the scene in which Ali and Stevenson pose as two opponents about to measure forces, Talese goes out into Havana’s open space. Another outside act. With his back to four fluted columns of Corinthian capital, between whose folds the soot of the buses and the crowded old American cars has been embedded, Ali poses again for the cameras. He hands over to health officials some medium-sized boxes with the label “Direct Relief International. Santa Barbara. California.” Red Cross Society, can be read on the pediment that, like the tip of an arrow, points to a blue sky like any other in the background.

Hours later, in El Morro, that place about which we Cubans have invented all kinds of jokes and phrases referring to our stubbornness: the time (“when El Morro was made of wood”) and the perpetual desire to go anywhere (“the last one to leave, turn off the lighthouse”), Talese remains agenda in hand. For him there are no shortcuts for a good story. “I spend as much time as possible with the people I write about, and patiently and provably ask them about themselves…over and over I repeat a few questions to make sure I have received a complete and thorough answer.”

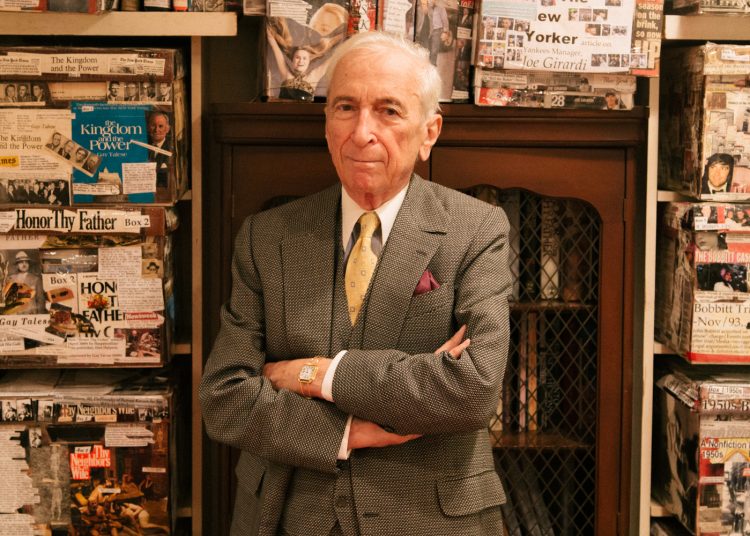

The Cuban sun is benign in January. It falls on his head as the Cuban receives any tourist, friendly. The insolent breeze shakes his short silver hair. Gay Talese is 64 years old and wears tailored suits, specially made shoes, hats that he imports from Colombia, Panama or France. Flawless, he can be seen through the alleys of the old fortification from which a cannon shot is fired night after night, at the La Lisa training center, where Ali and Stevenson make up another fight threat on the ring, visiting several hospitals , inside the minibus from which he observes the groups of onlookers who seem to want to devour them through the glass. Without variations in his attire, he will enter the reception that Fidel Castro will give them the night before boarding the plane on which they would return to their routines.

What can be understood as the vain attitude of an achiever seems more like a personal cabal. Talese has come up with a series of extremely interesting philosophical arguments in his long and fruitful life. He is convinced that dressing is something very serious; he believes that if one dresses well, and then looked in the mirror, he would be happier and healthier. The perfect projection is like a ray of regeneration on the individual. That’s why mirrors abound in his house. That’s why, and because he is the only child of the best tailor in Ocean City (New Jersey), in no public place does he lose his fine elegance of gray jacket, handkerchief slightly poking out of his pocket, shirt buttoned up to the neck and sober gestures.

The narrator of “Ali in Havana” is prudent and sober, but Talese enjoys the visit and has fun. Even with the fatigue in the group waiting for Fidel Castro on the night of the cocktail party, he laughs with the outbreaks of humor among those present.

He is inclement with the registration of the details, he barely looks up to discover elements that give color to his story: the gestures of Stevenson’s wife when she explains to Castro that she’s not the one he met as the boxer’s partner months ago, or the mimics of Castro himself because, politely fascinated by the trick that Ali repeated so many times during the visit, he has blurted out to everyone: “Ah, no, but where did he put it?”

Ali would tuck a fake thumb over his real thumb and make the scarf he had been shaking before the crowd disappear. He shakes it too and disappears there. The trick causes such enthusiasm in Castro that, in addition to a copy of the photo that Bingham had taken of the boxer with Malcom X in Harlem, during 1963, he received that illusory thumb as a gift. With his finger camouflaged by Ali’s fake finger, seen from the elevator on which they leave the cocktail, Gay Talese finished another of his expected profiles.

In the end, The Nation did not publish the work because it found it long and lacking the news factor. Neither did The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, GQ, Commentary, and a perhaps longer list. However, it is already inconsequential given the impact it achieved. “Ali in Havana” turned out to be one of the best essays published in 1997, after its appearance in Esquire, and has become part of the great texts of literary journalism, another of its author’s milestone.

“I think it was one of the most exciting experiences in my writing career,” he replies. “I could see two giants in world affairs, both extremely individualistic. Both had taken a position against the government of the United States. Ali refused to fight in America’s Vietnam War, and I celebrate him for that. Castro stood firm and persevering against U.S. attempts to replace him, and try to assassinate him. He is a great heroic figure, world class.”

Talese’s life is as fascinating as any of his stories. To conceive them, he has had to leave part of himself in each project before turning it into words, like the insect after molting, which after each change emerges stronger and more robust. In his case, according to testimonies from close friends, he seemed to emerge as a better person.

Someone who lives among orgy-prone nudists for months, also putting his marriage to the test out of the sheer interest of research, understanding and writing, has to be able to shed many of his uncertainties. His Catholic education was diluted, at Sandstone in his forties. Nor was it the same after tracing the past of Italian emigrants to America, as was the case of the Talese, the surname of a now reduced family, his, formed with their two daughters, Pamela and Catherine.

His visit to Cuba in January 1996 was in the context of a crisis exacerbated by “the end of a utopia” and the political pull between Cubans on both shores. The experience served him to evaluate as “regrettable” the embargo with which the governments of his country have subjected Cuba, in essence, for its communist ideology. “Unfortunately, relations between the United States and Cuba have been terrible,” he tells me: “I harbor no ill will towards Cuba. The people there have every right to decide what kind of government they want. The U.S. has tried to meddle in Cuban affairs for decades and decades.”

In fact, within a month of the humanitarian mission headed by Ali, things got complicated with the shooting down of two planes from Miami and the subsequent law promoted by Dan Burton, even with some objections from the Clinton administration. That story was long and Talese had begun to understand it on his previous visit, which coincided with the times when Ronald Reagan became president.

Talese remembers seeing an “impoverished” country “full of Russians.” Despite that, “I had a great time,” he says: “My wife Nan and I traveled outside of Havana to see various baseball stadiums and watch the games.” Then he was about to meet Castro, who used to appear unexpectedly in stadiums; however, the meeting was impossible until 1996.

What he can attest to is having made the most of his stay. “I enjoyed every moment I was in Cuba. People were extremely friendly,” he says. He even went so far as to prove the effectiveness of the health system when his wife was forced to receive assistance for dental problems. “The doctors there were not only courteous, they were very effective. She was cured of her ailment. Of course, the development of Cuban medicine is well known throughout the world. Doctors from Cuba are extremely talented and generous and are available, which is more than can be said for doctors from other countries.”

One of those days, walking through the city, he met Gabriel García Márquez. It was a year before he received the Nobel, although he enjoyed universal renown. “My God, what an honor to meet you,” he said Talese said, and the novelist came up with a phrase that sounded diplomatic: “An honor to meet you too.” But it wasn’t just courtesy; to his surprise, the Colombian had read his book that had just come out. Thy Neighbor’s Wife (1981) is the investigation with which he established himself as one of the best journalists in the world, capable of putting himself to the test with his family, in order to corroborate that American society had prospered in matters of sexuality.

García Márquez once asserted that the best interview he had read was the one that Talese did not do with Sinatra, leading to a jewel entitled “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.” Actually, it is an alternative to frustration. It is what he has always done, it seems to me: to give a twist to the established, to look for the other side of the visible, to change perspective so that, together with him, we all see an issue in a different way. Another of his philosophical precepts has to do with failure and the proverbial desire to prevent it. For him, cities like New York exhibit such splendid nocturnal life for a very simple reason: its most powerful citizens are not willing to be crushed at night, when their office empires are closed. In this way, seeking to feel “alive,” they have invented the vertigo of lights, casinos, theaters and cafes.

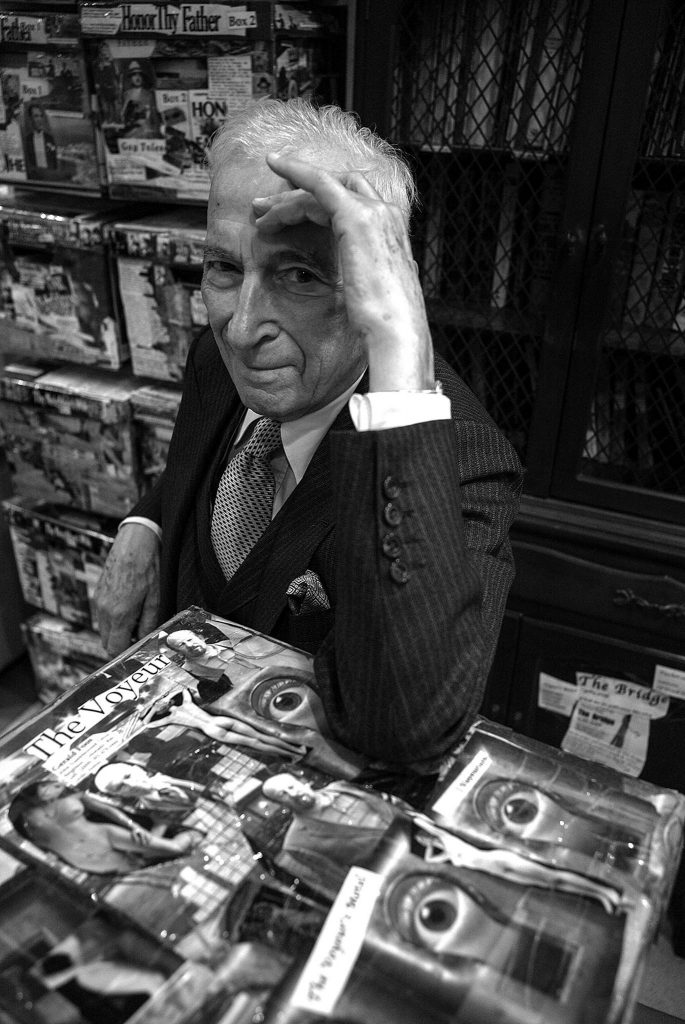

The papers and notes he collects to write each story pile up in his study like a curious piece of adolescent art. To help him visualize scenes and plots, he covers the surfaces of the boxes where he keeps them, with pieces that contextualize the subject he is writing about. With almost ninety years, he has formed an immense collage based on clippings, which could also be understood as one of his most accurate therapies. In this way, Gay Talese would seem to be one of the writer-journalists who has obtained the most emotional and psychological benefit from the profession.

He may have obtained more information, details, names and reasons about that Cuban trip of the 1980s, but this text satisfies part of an old curiosity. He owed it to me since university, when not even Tom Wolfe could satisfy my quests in journalism as much as Jimmy Breslin and Gay Talese. It matters little that I haven’t been able to question him until the doubts are satisfied, after stalking him for hours. Fortunately, he has been generous. Anticipating any anguish, he must have noticed it before I opened my mouth to justify this inappropriate manner of a journalist towards his interviewee. “We are doing the best we can,” he comforts me.

TN: Talese quotes were retranslated from the Spanish.

*This article was originally published by OnCuba in November 17, 2020.