There is nothing older than fragmenting the political field between the old and the new, or reading every reconfiguration as a fracture. Undoubtedly when the political forces of a country are replaced by emerging forces and/or actors, when the relations between them and the political organization/structure are transformed, when the norms of the political field also change, either through force or negotiation—negotiation is usually a way to avoid or put an end to political violence—we are in the presence of a “between,” a before and an after.

In Chile today there is no “political fragmentation,” on the contrary, polarization is put to an end like that disease that destroys democracy.

The country context

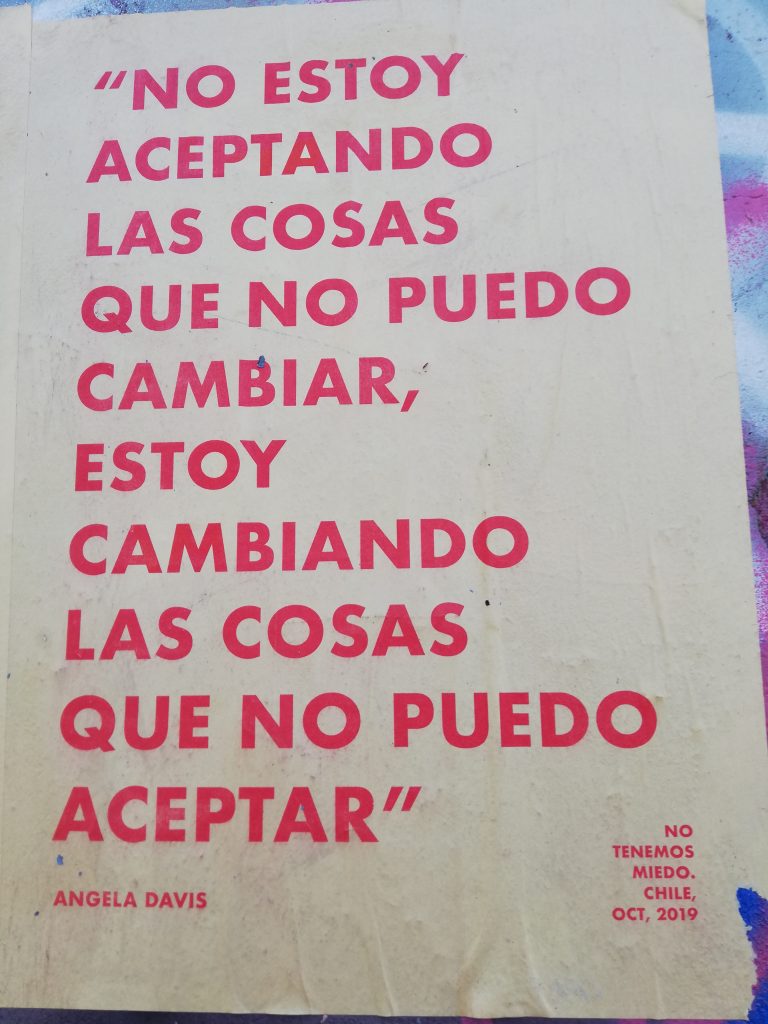

In October 2019, Chile experienced a “social outbreak” that had as its protagonists in the first place the students, the main political actor in the Chilean political field in the last 15 years (milestones: student mobilization of 2006 and 2011). Along with this, others such as the feminist movement (feminist revolution of 2018), No+ AFP movement, unions and grassroots organizations, had a strong presence in the configuration of actor-movements nucleated by strong social but also political demands. Grassroots organizations that confront the party system and the traditional political system, with strong criticism of the neoliberal model and the old duopoly political forces expressed in the bicameral system of representation.

October 18 marked an upheaval for all the country’s political forces, including the Broad Front (FA). This force irrupted in 2017 as a conglomerate of left-wing parties and organizations, a third political force against the parties of the Chilean right and also of the center-left, the latter “committed” to the Coordination (Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia) and then with the Nueva Mayoría. The Broad Front emerged putting an end to the duopoly of the Chilean political field, distributed between the old right and the old left of parties. Although it has been a force in which the student movement has had an important presence, as Carlos Durán (2020) affirms, it is also about “the continuity of an extra-parliamentary non-communist left.”

However, the outbreak led to a strong crisis of Chilean democracy—or perhaps it showed its weaknesses as never before in the last 30 years—, and this had its expression in the first place on the system of political representation. The outbreak quickly escalated from social demands to become a massive political movement: New Constitution was its first demand; Constituent Assembly, the second.

The political crisis in the country, under a constitutional state of exception, decreed for the first time since the return to democracy for political reasons, the human rights violations registered between October 18 and November 25, 2019 and subsequently, marked a break not only of the government but of the entire political field and of the Chilean democratic system.

On October 25, 2019, the Agreement for Social Peace and the New Constitution was signed. A long night that condensed the level of political crisis within the parties and the separation between them and the citizenry, between the latter and their leaders. The Communist Party (PC), or the Broad Front (FA) as a conglomerate, did not sign this agreement.1 This milestone opened the possibility of the National Plebiscite of October 25, 2020 where the approval for a new constitution won with 78.28%, and 79% expressed that it should be through a Constitutional Convention.

May 15 and 16, 2021 elections

This weekend the most important election in Chile in its political history took place: representatives were elected to the Constitutional Convention, the body that will draft the New Magna Carta. Said Convention achieved, as a result of the forces that promoted it and endorsed it in the 2020 Plebiscite: (1) gender parity—the only one worldwide in the history of constitutionalism, (2) 17 seats reserved for indigenous peoples and (3) the registration of independent candidates. These three requirements of the Constitutional Convention show the demands of a political field in transformation.

The candidacies were made according to Lists and not to parties, precisely as a result of the crisis of representation that they have evidenced. However, we cannot fail to observe that these continue to have an important sign and weight in Chilean politics, even within the so-called “independents,” a fact to be observed and followed with care. Here is a summary table of the main lists and the parties that made it up:

| Lists of Constitutional Convention | Parties | Seats obtained | % |

| Vamos Por Chile | Evolución Política, Partido Republicano de Chile, Revolución Nacional, Unión Democrática Independiente | 37 | 20.56% |

| Apruebo | Ciudadanos, Partido Democracia Cristiana, Partido Liberal de Chile, Partido por la Democracia, Partido Progresista de Chile, Partido Radical de Chile, Partido Socialista de Chile | 25 | 14.46% |

| Apruebo Dignidad | Comunes, Convergencia Social, Federación Regionalista Verde Social, Igualdad, Partido Comunista, Revolución Democrática | 28 | 18.74% |

| Independents in Lists or pacts | (Candidacies without political militancy but with affiliation in pacts associated to traditional parties in some cases) | 47* | 30% |

Drawn up by the author with SERVEL sources, with 99.91% vote count tables.

Main results

The results of the Constitutional Convention show a fall in the parties of both the right and the center-right (Vamos por Chile List), as well as the left and center-left (Apruebo List). An example of this is the dramatic case of the Democracia Cristiana, a historic party within the Chilean political field that has only achieved so far 99.91% of vote count tables according to SERVEL, to include two candidates within the Constitutional Convention, one of them being the president of the Party. On the other hand, a party like the Socialista, despite the blows it has suffered in recent times, mainly leadership crisis and corruption, manages to install 15 constituents.

Faced with these lists, a direct expression of what is read as a duopoly system, the Apruebo Dignidad List imposes a relevant force, with parties from the Broad Front and the Communist Party (PC) (7 seats), the most significant being the Democratic Revolution (RD) party, with 9 constituents.

But this weekend’s elections have not only been historic because of the Election of Constituent members but also because they were municipal elections (Mayors and Councilors) and Regional Governors (for the first time in Chile). The results cannot be read independently of each other.

If we observe, at the mayoralty level in the Metropolitan Region of 52 communes, 16 women mayors were elected (30%), and the irruption in the municipal governance of forces such as the Broad Front—especially the RD—, independents and the Communist Party. In a historic act, the latter won the mayoralty of Santiago Centro, a woman from the PC being the new mayor: Irací Hassler. Likewise, the triumph in the Ñuñoa commune of the RD Mayor Emilia Ríos and in Viña del Mar, Macarena Ripamonti also from the RD. What was achieved in these emblematic communes governed by the right for decades has been very significant because it is also about brand new female leaderships.

At the governor level, things are a little more difficult but they point to an equally interesting irruption, of the 16 regions of the country, 4 women managed to become governors (25%).

What these results show us so far:

- We are facing the end not only of the Pinochet constitution and with it the closure of the authoritarian enclaves that have remained in the long transitional process, but also the closure of a configuration of liberal democracy—which continues to be representative but under new rules of that representativeness.

- The political parties show a crisis similar to the one they are experiencing worldwide, but more than that, what is being expressed is the end of the duopoly of Chilean politics and citizen punishment of the political oligarchies.

- The weight of independent leaderships for the above reason, and of young and female leaderships (recognizing how the main social movements of Chile in its last decade are constituted in actors: student movement and feminist movement).

- The interesting formula between the FA and the PC, which, with a view to the presidential elections of next December, could produce a political force that is not at stake entirely in the risky “independence movement” and at the same time is capable of transforming and renewing its party structures and ties with citizens.

Chile is teaching a very direct lesson to liberal democracy worldwide and to the left in particular. There is a democratic way to win while changing these democratic rules. Thus it represents a milestone not only in its political history, in that of Constitutionalism, but rather in that of the vicious struggles between old and new political actors, old and new historical cycles.

Notes:

1 Among the parties that made up the Frente Amplio on October 25, 2019, only the Partido Comunes and Gabriel Boric signed in a personal capacity. Gabriel Boric is a figure who also represents the Chilean political reconfiguration: former student leader during the student mobilizations of 2011. Currently Deputy (FA), and possible presidential candidate in 2021 for FA parties.

* In these 47 seats the independents have the largest representation for the Pueblo List with 24 constituents. They are independents who define themselves “from the left without political militancy” and who emerged within the context of the Social Outbreak.