U.S. relations with its bordering countries have historically responded to a geopolitical logic. Caught in that logic, for better and for worse, is the question of the environment.

As is known, the United States and Mexico share an official program that includes 14 sister cities on each side. The U.S. government associates this program with a contingency plan with these 28 cities, foreseeing that they could be affected by “a major hazardous substance release.” Among those hazardous substances is, of course, oil. Something similar holds with Canada.

The Canadian border is 8,891 km; the Mexican, 3,145 km. Although that of the north is almost triple, everything indicates that problems related to the environment, together with other issues related to national security, accumulate much more on the Mexican side than on the Canadian side.

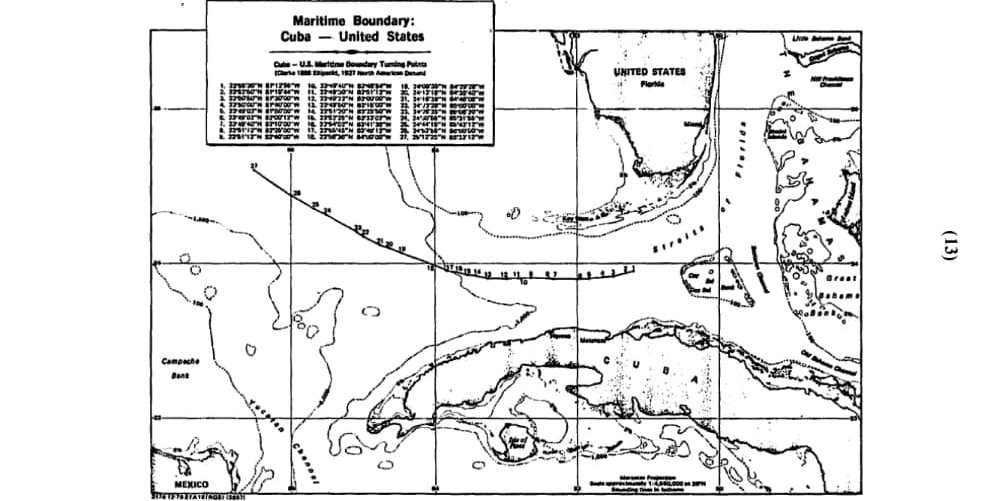

Any other border to guard? There is one with Cuba, which is not land, but maritime, and which is only 580 km. Despite their smaller size, those 313 nautical mile equivalents are not subject to the same control and cannot be physically sealed to the same degree as land borders. Agreed upon by a treaty on December 16, 1977, this Cuban maritime boundary, unlike the aforementioned land ones, is surrounded by a common sea, and is crossed by innumerable naval routes, as well as a current that rises from the south towards the coast of Florida, bordering the island, known as the Gulf Stream.

The geopolitical importance of this maritime boundary determined that the only treaty that emerged from the dialogue and negotiation between the two sides during Obama’s short summer was precisely the one that provides for the area of submarine exploitation in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, between the three countries. Marine exploitation that has a first common denominator in terms of the environment and natural resources: oil.

When the United States reacted to the Matanzas catastrophe, it recognized the existence of a precedent that authorizes collaboration in assistance to environmental threats related to oil spills: “United States law authorizes U.S. entities and organizations to provide assistance and response in the face of disasters in Cuba.”

The most immediate antecedent of mutual understanding of this declaration was one of the last signed between both countries, less than two weeks before Barack Obama left the presidency: the Cooperation Agreement on preparedness for and response to pollution caused by spills of hydrocarbons and other noxious and potentially hazardous substances in the Gulf of Mexico and the Straits of Florida, dated January 9, 2017.

The U.S. official assessment of that agreement was not limited to specific or technical aspects. Although its scope was aimed at “preventing, containing and cleaning up spills of oil and other polluting substances in the sea,” it was about “minimizing their adverse effects on public health, safety and the environment,” so that its meaning went further: “This bilateral agreement is a recognition of the importance of protecting our marine ecosystems and coastal communities.… To establish a mutual framework ― including diplomatic, legal and technical aspects ― to prevent, prepare for and respond to oil spills in the marine environment is particularly important for neighbors separated by 90 miles. The United States Coast Guard and the Department of State have developed a strong professional relationship with their Cuban counterparts.”

Although the Cuban side has recognized that that agreement was specific to oil spills in the sea, the underlying issue in that understanding, in terms of the national interest of each one, continues to be the protection of the environment of both, not only of the water.

After all, U.S. environmental policy does not make a substantive difference between maritime and land spills. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS): “an oil spill refers to any uncontrolled release of crude oil, gasoline, fuels or other petroleum derivatives into the environment. Oil spills can contaminate land, air, or water. Although the term oil spill often brings to mind spills in the ocean and coastal waters, such as in 2010 during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico or the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska, it also refers to spills on land. Spills are incredibly harmful to those species that come into direct contact with the contaminated areas. And depending on the size and scale of an oil spill, recovery time can take anywhere from days to decades.”

According to this definition, the United States and all its specialized agencies, which have an incredible wealth of technical resources and specialized equipment, in addition to the incomparable proximity to the disaster area, should have woken up on the Saturday morning in which the tank caught fire, in the mouth of the Bay of Matanzas, responding to their own interests: to prevent the pollution of land, water and air in a neighboring area, preserve the life of the species, and also that of the Cubans directly involved in the disaster.

Once the fire is over, it is not possible to imagine realistically what could happen from now on between the two parties, without first explaining what happened. The obstacle that prevented this unilateral and instant assistance cannot be attributed, as in the past, to the embargo regulations or any other law, nor to the technical limits of an agreement, but rather to the customary lack of political will. Against this impediment, no theory of ethnic lobbying or disaster diplomacy can provide an alternative interpretation, with greater explanatory power than what we already knew: relations characterized by hostility and mistrust, where it is difficult to develop any humanitarian diplomacy, because they rather lack humanity.

The question about the future of relations naturally does not depend on how many humanitarian missions can link the two countries. We already know that, too, since the two sides cooperated to deal with the earthquake in Haiti and the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. Of course, it’s possible. And?

Sister cities

In order to think about the future, in terms of alternatives, it might be useful to look again at the geopolitics of the Basin and, in particular, at the logic of the boundary between the United States and Cuba, returning, let us say, to the topic of sister cities, among other interlocutors.

Why is it that, despite the fact that there are sister cities on both sides, there are no border contingency plans that the United States can recognize and consider in its environmental programs? To the south of that border are Havana, Santa Cruz del Norte, Matanzas, Cárdenas; Key West, Naples, Sarasota, Saint Petersburg, Tampa, together with the Everglades protected area, and cities like Miami and Fort Lauderdale, to the north. If we look further, in the interior arch of the Gulf, there are the considerable ports of New Orleans, Mobile, Houston, with which Cuba has had very close historical relations, based on the same geoeconomic logic woven by their nearness.

We already know what happens when a hurricane or an oil spill multiplies catastrophes in the Caribbean Basin, whether by land, sea or air. We also know its impact on migratory flows and other national security problems that affect all U.S. borders, land or sea.

Reviewing the subject, however, it turns out that we do have “sister cities,” baptized that way on both sides, even without the consecration of the Environment Protection Agency or the federal government. Las Vegas and Santa Fe (in New Mexico) are twinned with Banes and Holguín; Brunswick (in Maine) with Trinidad; Sancti Spiritus with Philadelphia; Havana with Mobile; Pittsburgh with Matanzas. These subnational relations, recognized as an important dimension of foreign relations in current academic studies of our region, have not been insignificant between Cuba and the United States, including cooperation in recovery from natural disasters.

The classic example is that of the Cuban offer of aid to New Orleans, following Hurricane Katrina, in 2005. Cuba was, along with Australia, Germany, the UK, among the first countries to offer it, and among the very few (Venezuela, Pakistan) that were not U.S. allies. Although the United States was quite reluctant to accept it in general, which had disastrous results for the victims, it did not prevent the cities of Havana and New Orleans from creating their own cooperation channel, and a mission of Cuban doctors and health personnel from helping in the recuperation. Fourteen years later, this exchange was updated and was extended to culture, health, education, economy, tourism, agriculture, trade and scientific development, as well as disaster management, climate change and emergency preparedness, as well as management and urbanistic infrastructure.

Is the Cuban system an obstacle for this exchange involving subnational actors from both parties to develop as a major alternative? Does this antagonistic system result in expanding the space of relations between non-governmental actors, such as entrepreneurs, artists, academicians, scientists, church representatives, athletes, environmental activists, on both sides?

Based on the historical experience of the last ten years, and in the absence of a federal government initiative like the one in 2014-2016, is it more realistic to bet on the humanitarianism of U.S. agencies, with all the ties that often accompany them, or rather to a metadiplomacy that has borne fruit in the past, and that does not exclude Cuban public institutions, but rather turns them into facilitators?

Unless very unexpected things begin to happen in the coming days, when the last flame in Matanzas goes out, the hopes of those who two years ago eyed the victory of the Democrats as national salvation will also have turned to ashes. And that will also be a lesson.