Curves and sensuality are perhaps the two words that best define women’s fashion of the 1950s. While World War II (1939-1945) had brought modesty and contention in these dominions, during the postwar era the new look of designers a la Christian Dior and Givenchy moved the other way, a return to the glitter and splendor, but, at the same time, with explicit social messages.

“Women,” wrote a specialist, “had to concern themselves with their beauty, their aesthetic and their way of dressing. They had to be excellent housewives, wives, mothers and women at the same time.”

Dresses were worn tight and clinging, at times with thick belts to highlight the hips. The skirts were worm below the knees, with high heels for the figure’s greater visibility. Makeup highlighted the eyes, well-outlined in black, and lips absolutely red, as if to not leave any doubt about what it was all about. Frequently, handbags and furs were added to the portrait, together with pearl necklaces and diamond bracelets. A sensuality recreated in the TV series Magic City (2012-2013), of the Starz network, which tells the story of a Miami Beach hotel magnate married to an ex Tropicana chorus girl and with numerous ties to Cuba and the mafia.

Publicity and movies would do the rest. In the United States, Marilyn Monroe enthralled on the screens with an eroticism whose principal success, according to Norman Mailer, consisted in suggesting and not showing. Such a correct move was validated in an infinite number of her films, but especially in The Seven Year Itch (1955), in that very famous scene in which her skirt is flying in the air, standing on a New York subway grille, on Lexington and 52, or Some Like it Hot (1959), with a black dress showing spectators all her palpitating humanity and singing “I’m Through with Love,” a song by Gus Hahn, Matty Malneck and “Fud” Livingstone.

Meanwhile, Elvis, a white boy from Mississippi accused of appropriating things that didn’t belong to him, scandalously moved his hips: “You Ain’t Nothing but a Hound Dog.”

In Europe, Brigitte Bardot danced barefoot on a table – one of the most erotic shots seen in the world -, in God Created Woman (1958), by Roger Vadim, condemned by different religious organizations and censored in several countries because of the force of its images. In Italy, Gina Lollobrigida and Sofia Loren were the empresses of the bust in films like Fan La Tulipe (1952) and Two Nights with Cleopatra (1954), respectively, while in Spain the Sara Montiel of El ultimo cuplé (1957) saturated the spectrum of the bust with the cover of the record by the same name, highlighted by the scandalous yellow of her low-cut dress.

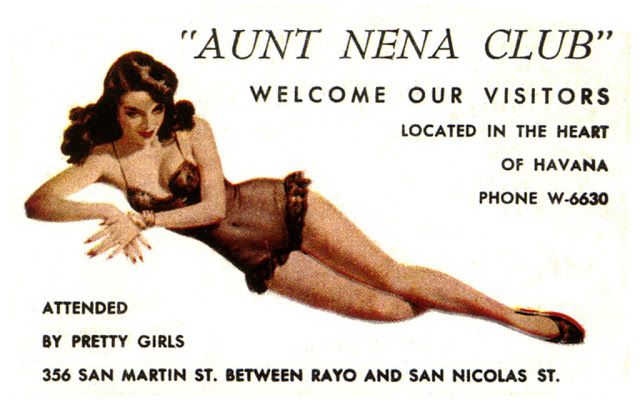

Havana was also Havana for its uncontained sensuality, but with its own history which that erotic avalanche could only react to, despite the social conventions and the dictates of tradition. Nightlife, with its increasing cabarets, casinos and nightclubs, in fact functioned as a powerful rein for a looser and more distended relation between the sexes in the midst of that equally sensual music that comprised the city’s sound, made up among other genres by the mambo, cha-cha and the feeling.

The end of that decade would be marked by the birth of a new star, the telluric Freddy, who according to José Agustín Goytisolo, had “such a deep voice and feeling…that she seemed to be singing with the vagina.” She shook Havana’s nights, first in the Bar Celeste, on Infanta and Humboldt, close to the Montmartre, Las Vegas and Radio Progreso, and later in the cabaret of the Capri Hotel, with her versions in Spanish of George Gershwin and Cole Porter, and with the songs of Marta Valdés, a composer who had recently come out, and of other authors of the moment.

But there was another type of life, also associated to those changes, and markedly red. According to several sources, referred to by Louis A. Pérez, in 1912 there were some 4,000 sex workers in Havana, a figure that rose to 7,400 in 1931 and reached 11,500 in the late 1950s, a 55 percent increase in a bit over two decades.

Around that same time, the city also had an entire infrastructure for the oldest trade of the world: some 270 brothels were operating. Their location in certain barrios did not prevent the existence of self-employed “ladies of the night,” like the ebony goddess which the young Guillermo Cabrera Infante bumped into in the surrounding areas of the Manzana de Gómez, with whom he went to forge steel for the first time for one peso, plus the same price for the hotel room, an entire institution of Cuban sex culture that today is extinct, at least as it was known until then.

Places like the barrio of Colón became emblematic islands of sex for rent, even during its decadence toward the second half of the 20th century. In that place were the brothels of La Gallega, one of the most famous of the capital, but there were also those of a higher class in La Victoria, in the very Centro Habana and in Miramar, for clients with greater purchasing power in search of specialties and sophistication.

A metaphor was popularly used to name the women like those of the Manzana de Gómez, and also of the Monte and Cienfuegos streets: “fleteras” (charters), which according to Manuel Moreno Fraginals comes from a word from the military and maritime Havana of the colony. “Fletero or fletante,” Moreno affirms, “is the person who chartered a ship or part of it to transport persons or merchandise” in a township of San Cristóbal that offered a plurality of services to a population of soldiers, sailors and gamblers, and also had the so-called slaves paid by the day or “earners,” many of whom prostituted themselves to pay their masters for their freedom.

Obviously, the Americans did not introduce prostitution or gambling in Cuba. But they contributed to raising their profile in a scenario of domestic crisis, through a wide-ranging network of services and officiants when the mafia stormed Havana and a tourism of hundreds of weekly flights started coming from Miami, Tampa, New York, Chicago…, together with the visitors who came by sea from Key West or other points of the continental geography like West Palm Beach and New Orleans.

In 1950, 194,000 U.S. travelers had landed; seven years later, in 1957, they already were 356,000. They came from all classes and social groups, in keeping with a moment in which tourism had been democratized with the low prices for transportation and accommodations due to the changes in the economy and specific market strategies and competition.

All this was occurring in the context of that erotic-sensual emergence in fashion, publicity and films, in which they left at home the restrictions and taboos proper of the puritan morale. The visitors came, of course, to the rooms of those recently built shining hotels, and to gamble their money in casinos and game rooms. But they also came for “romance” with the other, no matter what their sexual orientation was, and, of course, to enjoy the rumba, the rum and cigars.

Havana, Cuba, was definitively a place where “conscience went on holidays.” The Camelot of the libido.

The lack of critical a approach in this article to prostitution, to the exploitation of women, to vice and to the degradation of society, is surprising. One is left with a nostalgic message, as if sensuality was the driving factor in the corrupt society of the 1950s.

Excellent comment!