With more than 50 years of legal and institutionalized practice in Cuba, and a more flexible and tolerant interpretation than in many other nations in previous decades, abortion has not been a taboo subject on the island for a long time. The voluntary interruption of pregnancy is assumed mostly as legitimate and acceptable on a social level, while it is considered a conquest, a right earned and maintained, both by the authorities and by activists, experts and a good deal of the female community.

However, this right — included in the group of sexual and reproductive rights enshrined collectively in the Cuban Constitution — does not escape controversy today, a controversy fueled by the advance of conservative and fundamentalist currents, both in the world and in Cuba, their growing influence at the political and social level, and their dispute over norms and rights already established or in the process of construction and debate. And, on the other hand, by the consolidation of activisms that, especially from civil society and the academic environment, confront these conservatisms and summon the political power to maintain and expand what is already regulated.

Although the phenomenon is not exactly new in the Caribbean country, several factors have worked in recent times as a backdrop to a dispute that has been rising in tone and has made each party position itself more strongly — not only at the level of discourse, but also of concrete actions — in the face of a presumably greater escalation of the controversy. Outside of Cuba, mention should be made of the extensive legislative, social and political debates on abortion in several Latin American nations in recent years, which have led to the rejection or approval of laws on this matter, and the consequent confrontation between movements in favor and against this practice — the so-called green tide (pro-abortion) and blue tide (anti-abortion) —, and also the recent decision of the U.S. Supreme Court to reverse the historic Roe vs. Wade ruling, which supported the right to abortion at the federal level, leaving millions of women at the mercy of the conservatism of many state legislatures.

Meanwhile, in Cuba, first the debates and public consultations on the Magna Carta and, recently, those focused on the new Family Code, even though they have had other issues — such as same-sex marriage, adoption by non-heterosexual couples and gestation solidarity — as the focus of the greatest discussions, they have shown the increasingly visible struggle of conflicting and even antagonistic positions on sexuality, reproduction and their associated rights, and have brought to light the power of influence of religious movements and other conservative currents, to the point of provoking the postponement of the possible legal support for same-sex marriage from the Constitution to the Family Code, something that will finally have to be decided in a popular referendum on September 25. In this way, it is not unreasonable to foresee new and bitter public disputes around related issues, such as the voluntary interruption of pregnancy.

“Shielding the right”

Given the current national and international scenario, the Cuban authorities have reiterated their consideration of abortion as a right and have assured that they intend to include it in a new health law that is currently being worked on. In addition, they have defended the policies applied on the Island for more than five decades in order to facilitate free access to this practice, in institutions of the state health system, and thereby avoid maternal deaths due to risky and unsafe procedures.

“We are clear that women’s access to voluntary interruption of pregnancy is a right, a right that is backed by a medical, legal, free and safe procedure, and is thus established in Cuban regulations. This issue has been recurrent in recent times, given the advance of fundamentalisms and conservatisms that are putting at risk in the world and in the region a fundamental conquest of women’s health,” Cuban Minister of Health Dr. José Ángel Portal Miranda recently stated at a press conference, in which he addressed various issues and programs related to the current situation in his sector.

“Where abortions are legally restricted, women are more likely to go to untrained service providers or undergo procedures under really risky conditions,” said the head of the Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP), who emphasized the risk that this represents for the lives of women, “because what is certain,” he said, “is that she who wants to interrupt her pregnancy is going to do it clandestinely, unsafely and in non-aseptic spaces.”

Portal Miranda highlighted the fact that Cuba was “the first country in Latin America and the Caribbean to legalize abortion in 1965,” and explained that the island “has built its legal base on three fundamental principles: women are the ones who decide about their body and whether or not they will carry their pregnancy to term; the intervention is totally voluntary and is carried out in controlled health environments and by specialized personnel; and it is a totally free practice.” The legalization and institutionalization of this practice, he maintained, “was a measure aimed at reducing maternal deaths, which at that time was estimated at more than 120 deaths per 100,000 live births, and aimed at promoting the full exercise of the right to decide on reproduction.”

As the minister explained to the press, “in Cuba the interruption of pregnancy is established under the use of informed consent, for the authorization in all cases of the woman or her legal representative, in case the pregnant woman is underage, or is not physically or mentally fit.” Abortion, he specified, is allowed on the island up to 12 weeks of gestational age “by voluntary decision of the woman and without restriction as to her reason,” while up to 26 weeks it is authorized in the case of “fetal malformations incompatible with life,” a responsibility that falls on a national commission of experts from different specialties and “always with the consent of the mother.” To carry out these procedures, he added, “hospitals with gynecology and obstetrics services are defined within the health system, and polyclinics are also accredited to carry out menstrual regulations, for patients with a menstrual delay of up to 45 days, counting from the first day of the last menstruation.”

But, beyond what is institutionally regulated in MINSAP rules and protocols, the head of said ministry confirmed the government’s intention that the voluntary interruption of pregnancy be supported in the next Health Law. The previous legislation, still in force, dates from 1983, which is why 39 years have passed since its drawing up and approval in a different socio-cultural context and under the protection of an already superseded Magna Carta. On that occasion, as activists and scholars of the subject have emphasized, abortion was contemplated in the associated regulation, but not explicitly in the law itself. Thus updating this regulation, in tune with the current scenario and with the rights enshrined in the current Magna Carta, is the challenge assumed by the authorities of the sector, in the midst of an ascending and not always hidden dispute over these rights between certain social actors.

“Reproductive rights include equality, non-discrimination, health, reproductive autonomy, information and integrity,” defended Portal Miranda, who specified that “these are issues that must be included in the next Health Law, which must be approved at the end of the year and which is currently being worked on. The policy for the law has already been approved, and among the elements that will be supported in it are those related to all these rights of Cuban women, including the voluntary interruption of pregnancy.” In this new legislation, the minister stressed, “we aspire to further shield this right in the face of the appearance of fundamentalisms and conservative attitudes. This is why we are foreseeing it precisely as a right. We are proposing it that way in the law.”

Abortions and family planning

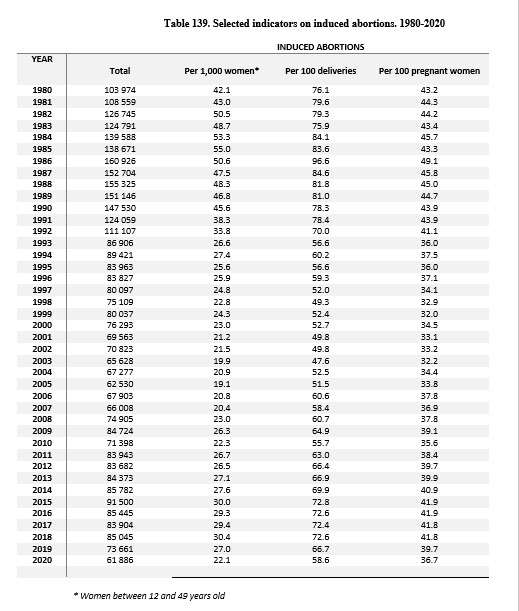

According to statistics cited by Portal Miranda, some 56 million abortions are performed in the world every year, of which around 45% are performed unsafely. In Cuba, the official figure went from more than 150,000 at the end of the 1980s to less than 62,000 in 2020, according to MINSAP statistics, although this decline has not been sustained and has had ups and downs in its evolution — in the early 2000s, for example, it fell below 70,000 for several years, and then in the second decade of the century there was an increase, with a peak of 91,500 in 2015. In his press conference, the minister defended the reliability and transparency of these figures, which, he said, “are recognized by international organizations linked to the issue” and, on being compiled institutionally throughout the island, “make it possible to know the behavior of the phenomenon within the country and also define the characteristics of that behavior in each of the territories and at each moment of the year.”

With these elements in hand, the head of the MINSAP asserted that the numbers confirm “a discreet trend” towards a decrease in abortions and menstrual regulations on the island, particularly in recent years, and he maintained that “the voluntary interruption of pregnancy in Cuba has not been decisive in the current decline in fertility,” a phenomenon that has a negative impact on the current demographic dynamics of the island and results in the sustained growth of population aging. Official figures show that this downward trend in abortions and regulations is also reflected — although also discreetly and with ups and downs — in the rates of these procedures performed per thousand women between 12 and 49 years old — the ages considered in the MINSAP database —, for every 100 deliveries and for every 100 pregnant women, according to the table on the subject of the 2020 Health Yearbook, the last published to date.

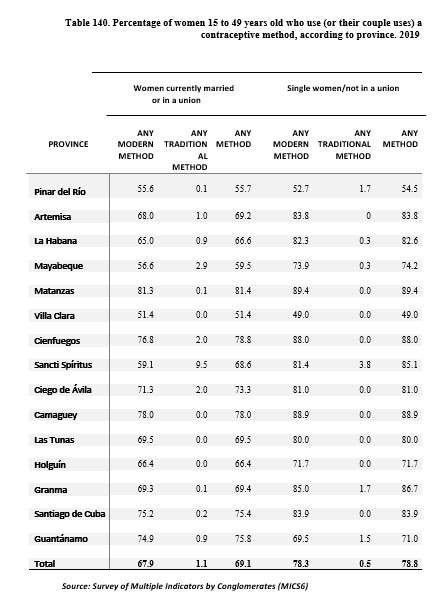

In this regard, Portal Miranda considered that “this decrease has been based on educational programs, both general and sexual education — an aspect questioned by sectors of independent activism and academia —, as well as the availability of varied, efficient and effective means and contraceptive methods,” although he pointed out that “all of this can be improved.” “Right now, for example, we have a significant contraceptive deficit, that’s no secret to anyone,” he acknowledged when asked about this in the press conference. “We have had difficulties acquiring them, because they also compete with other resources necessary for our sector and that define people’s lives, so we must prioritize them in the midst of the complex economic and financial situation that the country is going through, intensified by the blockade of the United States government.”

However, even with the decrease shown by the statistics, the minister emphasized that “today it is considered that the volume of voluntary abortions (performed in the country) is high.” “For us,” he said, “even though it is a figure that has been decreasing, the main purpose is to reduce this practice to the essential minimum, and we have not achieved it. Therefore, we are going to continue working on this matter.”

“Cuba,” he added, “defends a public family planning policy that allows for a conscious decision to be made about the number of children to have and when, as well as advocating the implementation of a process of accompaniment for women in their right to decide on their body and abortion is left as a last resort in the face of an unwanted pregnancy. In this way, a legal, safe, free and feminist practice can be ensured. Maintaining this perspective within a voluntary interruption of pregnancy implies being aware that it is not enough just to carry out the procedure, since much more is required for women to fully enjoy their right to sexual and reproductive health.”

To reduce the number of these clinical procedures and promote other methods, in correspondence with coherent and healthy family planning practices, the MINSAP has a country-level strategy, according to the minister. “The goal is to spread non-invasive techniques for the voluntary interruption of pregnancy,” Portal Miranda explained, “mainly the drug method with Misoprostol, a protocol that aims to carry out 80% of all voluntary abortions with this method, without abandoning, as it is logical, the development of institutional services to increase the safety, resolution and effectiveness of this practice.”

“We have been insisting on the prevention of unwanted pregnancy,” said the minister, who stressed that abortion “is not a contraceptive method, since its indiscriminate use can put women’s sexual and reproductive health at risk.” In the current Cuban context, together with the desired legal recognition of the voluntary interruption of pregnancy, the head of the MINSAP highlighted the importance of “continuing to work and provide information to our women about all the possibilities and services in this direction that exist in the national health system. That it be known how to access them, and the support that our system provides to the bodily autonomy, life and health of women.”