After decades of lurching and putting on the brakes, the Cuban passenger railroad is trying to recover. The recent arrival of 56 Chinese cars, as part of the 240 agreed between Beijing and Havana for the next months, worth 150 million dollars, has started to materialize the intention of giving back the lost dignity to this means of transportation. Or at least, some of that dignity.

These are the first cars with zero mileage that have arrived to the island in 44 years. They will be joined by another 24 within a few days to complete the first batch of 80 that, according to Cuban Transportation Minister Eduardo Rodríguez, “will be in service this summer.”

Since 1975, long before the fateful “Special Period” and even the “golden” 1980s, did such “brand-new” wagons disembark in Cuba.

Not even those of the trains popularly known as “Locura azul” ―because of the color of their cars reminiscent of the film about Los Zafiros― and “the French” ―because of their country of origin―, were brand new. The most “luxurious” Cuban travelers remember in the last three decades already had quite a bit of mileage when they began being used in Cuba. And because of that “experience” the situation worsened.

As a consequence of these and other debilitations, Cuba has suffered for years from a chronic dysfunction of its passenger railroad. That, despite having an ideal geography for railroad transportation and a history that places it as the first country in Latin America ―and the seventh in the world― to hear the whistle of locomotives back in 1837.

With no spare parts, financing or effective management to guarantee it, the used cars that were used thousands of times started deteriorating, changing them for others equally or more used and less comfortable, or for others that were “repaired,” more like a torture chamber ―due to their “comfort,” continuous delays, bad lighting and terrible hygienic conditions― than a vehicle to travel properly.

The deterioration was not exclusive to the cars, and also reached the locomotives, stations, workshops and thousands of kilometers of rail tracks, a fatal combination that spaced departures ―from being daily, they passed to alternate days and then every three or four days―, canceled routes, timetables extended ad infinitum and a drastic decrease in the annual number of passengers.

Numbers don’t lie. While in the mid-1980s, when economic stability based on ties with the former Soviet Union offered travelers more options, in Cuba around 24 million people traveled by train per year.

A short time later, in 1992, the historical record of 33 million would be reached, despite the already severe economic crisis, thanks to the fact that the technique and infrastructure inherited from the previous decade were still in good condition, while the shortage of fuel affected road transportation.

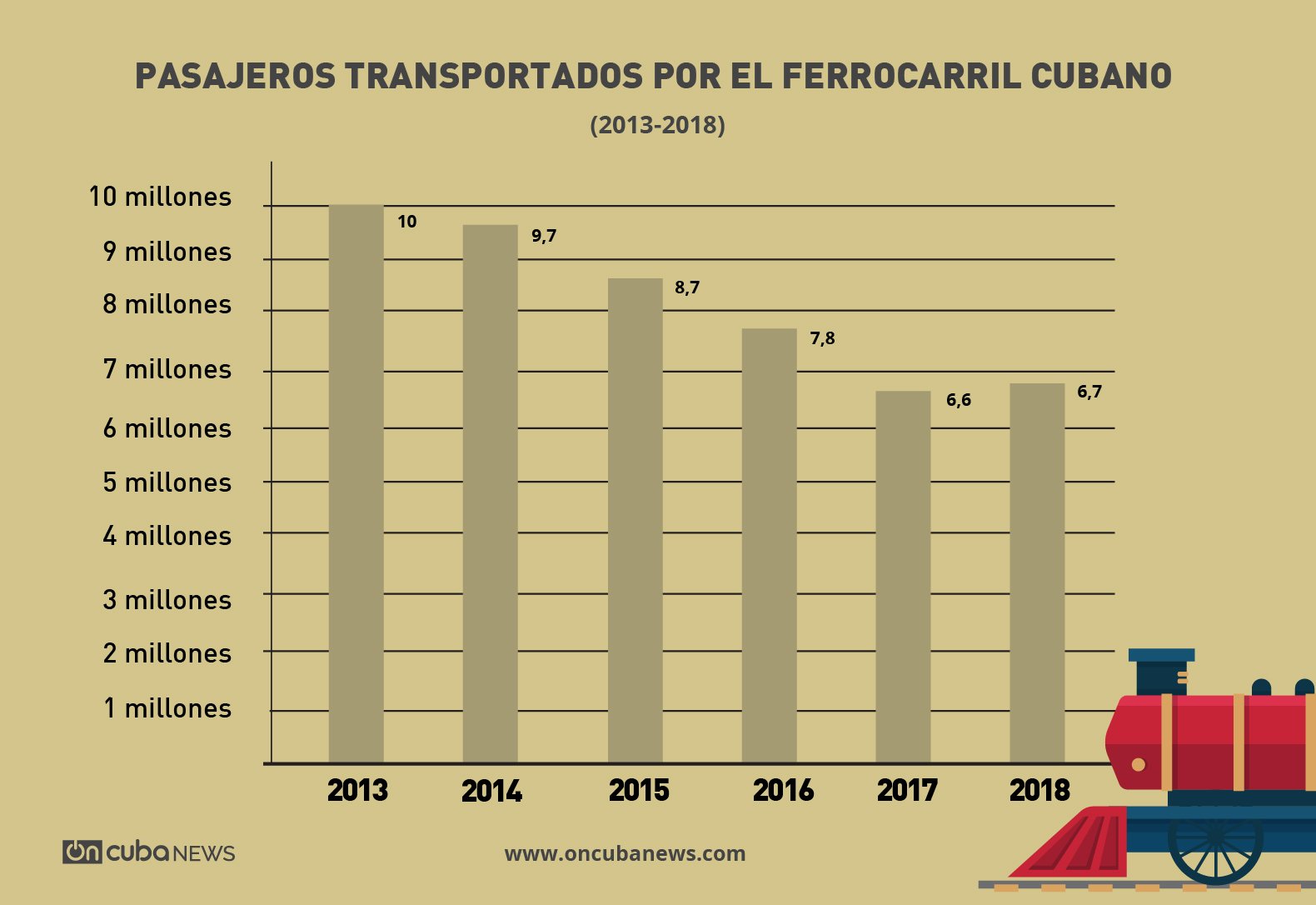

However, from then on, the figures would start decreasing. In 2000 they had already fallen to 16 million and the drop would continue to 6.7 last year, a figure similar to that of 2017.

——————

*Caption

PASSENGERS TRANSPORTED BY CUBAN RAILROAD

Millones = million

In addition, traveling by railroad in Cuba became a reckless experience. And it still is. Getting on a Cuban train is an adventure whose beginning is known ―when the train starts, which often does not coincide with its official departure time― but not its end; in which you can find anything in the cars ―from the “affectionate” German cockroaches to domestic and farm animals― and where going to the bathroom requires a high dose of courage.

However, for many it remains a necessity. While the national buses and airplanes raised their prices to considerable levels for the average Cubans, the trains have kept their prices more accessible. A simple example: traveling from Havana to Santiago de Cuba costs 169 Cuban pesos (CUP) by bus and 220 by plane ―the average salary on the island is around 760 pesos, but 1.7 million pensioners get an average of 280 pesos―, while the train costs only 32.

That difference is enough to tip the scale, even though, on average, Cubans travel an average of fewer kilometers on train every year

————–

*Caption

AVERAGE DISTANCE PER RAILROAD PASSENGER IN CUBA

The coming trains

The arrival of the new Chinese cars will make it possible to “reinforce” passenger transportation between Havana and the east of the country, according to Cuban authorities.

Their startup is part of a program for the recovery and development of the island’s railroad until 2030, “which includes the entire system that goes from the cars and locomotives to the modernization of communications,” according to Eduardo Hernández, general director of the Cuban Railroad Conglomerate (UFC). The total investment is estimated at around 3 billion dollars.

As part of this, more than 40 locomotives ―out of a previewed total of 75― have already arrived on the island from Russia as well as the first experimental prototype of a diesel railcar. The agreement with Moscow includes technical assistance to Cuban specialists, the delivery of spare parts and the modernization of workshops, as well as the rehabilitation of the main tracks. In addition, the door has been opened to investments from European countries such as Spain and France.

Cargo transportation is one of the central aims of the program, and the intention is to move from the 13.5 million tons transported in 2017 to more than 22 million in 2022. As for the number of passengers, this year the UFC expects an increase of one million with respect to 2018. In this way, 2019 would approach the 7.8 million of 2016, still below other previous numbers, but at least above the 6.6 of 2017, a negative peak to which the aim is not to return.

—————-

*Caption

PASSENGERS TRANSPORTED BY CUBAN RAILROAD

Millones = million

For this leap, the return “in the second semester of the year” of the Havana-Holguín route, suspended since 2006 and that initially will start every three days, was announced. As well as trips to Santiago de Cuba on alternate days, and to Guantánamo and Granma with the same frequency as Holguín.

“A process of recovery of quality has begun, with greater comfort, reduced travel time and the reestablishment of departures that today remain canceled,” confirmed Minister Rodríguez at the reception of the new cars. Then, he called for “working so that what is reborn endures in time with quality and stability.”

If this were to be achieved, the imbalance faced by the railroad would begin timidly diminishing with regard to interurban buses, by far the most used modality by travelers in Cuba ―if we rule out private trucks, whose statistics are impossible to calculate― and that, unlike the train, has experienced sustainable growth and in recent years has remained stable at more than 140 million passengers.

——–

*Caption

PASSENGER RAILROAD VS INTERURBAN BUS IN CUBA

(SELLECTED YEARS)

PASSENGERS

YEARS

RAILROAD

INTERURBAN BUS

Millones = million

However, the increase in comfort will surely come with another increase: that of prices. Although it has not yet been officially said how much the tickets will cost, it seems logical that a trip in the gleaming Chinese cars will not cost the same as in the “mistreated” ones still used in the country. Or, at least, not in all of them.

According to the transportation authorities, the new passenger trains will have “large locomotives” and first- and second-class cars, with different prices. The first, obviously more expensive, will have air conditioning and internal television circuit, while the second, more economical, will have fans and audio system.

The two types of cars will have 72 reclining and rotating seats, two bathrooms “excellently fitted out” and a cold water fountain, and in their trips they will take especially trained railroad attendants for their services and will have a cafeteria wagon, which also arrived now from China.

This differentiation of categories ―and prices― is not new in Cuba’s railroad. For example, the “French” train, which started being used at the beginning of this century, also had two classes, the first one for 72 pesos and included a sandwich and a canned soft drink. However, cases like this have been the exception in a public transportation system where an anachronistic egalitarianism reigns, very distant from the current Cuban reality.

The change not only points to residents on the island, but also to tourists, as confirmed by the UFC’s general director. And although foreigners will most likely not pay the same as the Cubans, sights are also set on them and this gives an idea of the future cost of the tickets.

But beyond new routes, categories and prices, the recovery of Cuban passenger railroad is not a matter of a few months. Or years. The complete rehabilitation of the tracks is still pending so that the trains can travel at a higher speed, and the construction or restoration of stations throughout the Island, including that of the capital itself, on which work has been underway for some time and whose completion, despite the expected date (2019), is difficult to predict.

And all this, in the midst of a complicated economic situation, which could “even worsen in the coming months,” according to former President Raul Castro in the National Assembly in April, spurred by the crisis in Venezuela, the recent measures of the U.S. government and domestic inefficiency.

The journey, for the moment, doesn’t seem simple. Nor fast.