Day after day, Oveida Hurtado, 64, lights a candle for her late mother in her apartment in the Vista Hermosa neighborhood in Ciego de Ávila. Oveida, who has suffered from Raynaud’s disease for more than a decade, does not ask the spirit of her mother for protection and health for her, but for her son Yosvel, who since June 2019 has been held in the Stewart Immigrant Detention Center, in Georgia, United States.

“That is daily and it is sad, very sad, all that suffering,” said to OnCuba Yania Ferrer, Oveida’s daughter and Yosvel’s only sister, who remained on the island, in charge of taking care of her parents, when her brother decided to emigrate.

Yosvel Ferrer Hurtado, 40, a Bachelor of Computer Science, single and without children, had had work problems in Cuba according to his sister because, despite relating “well with everyone” and being professionally prepared, “he did not agree with the politics of this country.”

Yania says that “in the end, due to that situation, doors started closing and then he decided to take an opportunity outside the country.” He was first in Chile, from where he returned to Cuba to see his father, who was very frail, and then “to see if in the United States he could get ahead, because what he wants is to work and help the family. But since he arrived it’s been horrible, a terrible situation,” she explains.

Stewart Detention Center

Along with other immigrants from Cuba and various countries, Yosvel has been in the Stewart Detention Center, located in Lumpkin, Georgia, for 15 months. The 1,916 beds in this private center, contracted by the federal government, make it one of the largest of the around 200 that the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has, which instills fear in hundreds of thousands of people in that country, the main destination of international emigration since 1970.

In August 2019, Yosvel was transferred to Stewart, after a tour of different institutions, in which he spent 36 days without being able to bathe and was diagnosed with scabies.

In Stewart there are immigrants in an irregular situation, who are trying to reverse their deportation processes by legal means or who have already exhausted all resources and are waiting for the flight that will take them back to their country of origin.

The center’s website clarifies that “detainees cannot receive phone calls.” The authorities provide a number “to leave an urgent message” and assure that “the message will be given to the detainee.” They can receive visits from family and friends (during restricted hours), legal representatives, clergy and consular officials, prior coordination. They can also participate in video calls.

His family clings to the Yosvel on screen. Yania says that for a short time they have been communicating more regularly through a tablet her brother was given and that allows him to make video calls for which he pays, thanks to his work in the warehouse of the detention center. They also do it through some free calls “he is given weekly after COVID-19 and which he uses to speak with us.”

However, his calls don’t just bring joy to the family. As well as sadness and worry.

“Before we started to communicate by video call, we had never seen the center where he is,” says Yania, “but since he started the video calls, we have been able to clearly see how bad the conditions are there.”

Yosvel has suffered from asthma since he was a child and that makes his condition even more fragile. Yania says that from Cuba they have sent “the summary of his medical history, the methods and treatments that have always been applied to him, and there they do nothing with that. Many times the laundry is brought to him wet and he has to put it on like that, because if not, what is he going to wear? A thousand other things like that.

“He has had chest pain, he has felt bad, he has asked to be taken to the doctor and they have not taken him,” she continues. “They have let the days go by and after a week they have taken him, and when he has communicated with us we have consulted a doctor here, who has been our neighbor for a lifetime.”

The threat of COVID-19

An investigative piece by The New York Times and the Marshall Project reveals that ICE contributed to the spread of coronavirus inside and outside the United States, by continuing to detain people, moving them from one state to another and deporting them.

According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, between February 3 and April 24, 2020, there were 232 probable ICE deportation flights to 11 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Several deportees became sources of contagion for the countries to which they returned, whose governments were pressured in many cases by the Trump administration to continue receiving flights of this type. This, together with the security risks at airports, turns the ICE air arm into “an internal and external threat,” according to research by the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

The investigative piece records a deportation flight to Cuba in the week of February 24 to March 3. The media confirm that 119 people were deported, who flew from the Miami airport to Havana. On March 24, the island’s government closed the airports for the arrival of regular flights, a measure that was maintained until November.

For this investigation, OnCuba consulted the Cuban consular authorities in the United States to find out if they were aware of the situation of the detainees and if a solution would be given with a return to normality, but received no response. They told Yosvel’s family in Cuba that “they did not open for the flights that normally bring deportees.”

In the detention centers, the risk of contracting the coronavirus has been well documented. From April to August 2020, the average monthly case rate among detainees was 13.4 times that of the U.S. population. Mass infections and even deaths while in custody have drawn attention to the precarious conditions in the centers, as reported by the NYT piece and the Marshall Project, which also points to scattered testing.

Conditions like those described by the group of 103 Cubans detained in Stewart made them turn to human rights organizations and organizations that defend immigrants, in search of support. These are common situations in other detention centers in the southeastern United States, for example, in Louisiana and Texas, as stated by Amilcar Valencia, executive director of El Refugio, an organization that provides support to families of detainees.

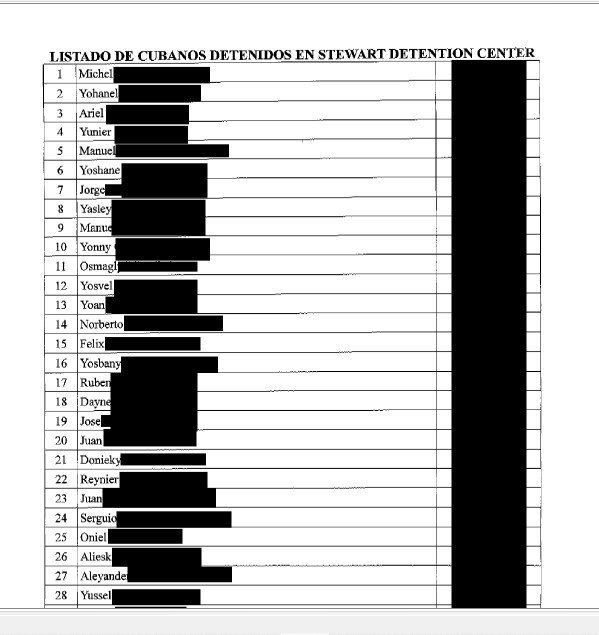

LIST OF CUBANS DETAINED IN STEWART DETENTION CENTER

In Louisiana, the Southern Poverty Law Center describes the context as suicide, self-harm, medical negligence, isolation and lack of legal advice in which a group of more than 100 Cubans live, in favor of which this NGO that defends civil rights presented a class action lawsuit for their release.

In filing the lawsuit, it is argued that ICE’s refusal to review the release of asylum seekers on a case-by-case basis “violates federal law, costs taxpayers millions of dollars each month, and causes untold suffering to the men and women who seek legal protection inside the United States.”

On the second point―the cost of stays in detention centers―Public Citizen, a non-profit organization based in Washington, reveals that spending on immigration and correction centers doubled in a period of six years during the administrations of Obama and Trump. The report titled “Detained for Profit….” reveals spending of more than 2.3 billion dollars in 2018 on federal contracts with just 10 contractors. The figures show a concentration of the administration of these centers by private agents.

The U.S. Immigration Council points out that, in 2019, to exceed the spending approved by Congress, ICE used budget mechanisms to transfer money from other lines of its administration to detention centers. This is how it supported its historical record of more than 55,000 detainees.

The Stewart Detention Center receives an allowance of 62.49 dollars per person per day from the U.S. government. Among the group of Cubans detained there, the idea that keeping them in the facility is part of a business becomes a frequent topic. “We are their source of income,” says one of them in videos accessed by our team through the Southeast Immigrant Freedom Initiative (SIFI), an organization that provides free legal representation to detained immigrants.

It’s reports point, first of all, to general problems in the center: lack of toiletries, overcrowding, mistreatment, pressure to sign documents such as the deportation order, lack of information on the part of immigration officials and, above all, the indefinite prolongation of their detention. These Cubans have been detained in Stewart for periods ranging from one to two years, without being released under supervision orders while their appeal processes conclude or the flight that will deport them takes place.

Erin Argueta, SIFI’s main lawyer, tells OnCuba that “they were not given a fair opportunity to request asylum outside of detention, despite being able to demonstrate that they were not a danger or a risk of flight. They were detained since they arrived at the border. They were not released on parole or on bail. When they protested peacefully for what they perceived as unfair treatment over the months, they were violently repressed,” says the lawyer.

Second, the reports of the Cubans detained in Stewart refer to the lack of protection measures against COVID-19.

“Once the pandemic began, all of those detained at Stewart faced an unreasonable risk of exposure to the virus and the inability to maintain a safe distance from others while living, eating, bathing, watching television, and waiting to use a limited telephone number in confined spaces,” says Argueta.

Yania says that in her brother’s case “at first they didn’t even give him masks. He tied a sweater over his face so as not to catch it. Then they started giving them out, but only every so often, as with hygiene products and everything else.”

Until October, 364 people (between detainees and workers) had contracted the new coronavirus in Stewart. Three detainees had died. Argueta adds that many detainees had to be hospitalized, while others faced the disease within the segregation.

In the videos, a detained Cuban says that he spent 14 days ill “in a pit.” “That is the isolation that occurs here,” he emphasizes. Another reports that he was ill for a week, without receiving medical attention, and that he was later returned with his companions without performing any tests.

The fear is greater for those who, like Yosvel, suffer from respiratory diseases or others that are risk factors for the coronavirus. Argueta maintains that these detainees requested their release as the virus spread in the institution, but most of their requests were not answered. “Even when federal courts and criminal courts across the country ordered the release to protect people,” she concludes.

Yosvel was transferred in November to a “bunker” with 14 people suffering from respiratory diseases, which implied a small improvement, since in the previous one 62 detainees lived together in a closed space. In December, his family continues to be concerned about the spread of the virus in Stewart.

Seeking asylum

In a letter that he has sent to human rights organizations, the press and all entities and people who want to hear his story, Yosvel relates that he and his companions voluntarily surrendered to agents on the border between Mexico and the United States, in Texas, upon arrival in the country in 2019. Other detainees insist that, by surrendering, they sought to “do things right, legally.”

According to a 2009 regulation, asylum seekers who surrender to immigration authorities at border points must be released under parole, if they prove that they are not a danger or risk of flight. The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that, under the Trump administration, approval of paroles for asylum seekers dropped dramatically.

For many detainees in Stewart, arriving on U.S. soil after traveling long routes through Central America, exposed to a great deal of violence, represented the beginning of a life. However, it was not what they imagined it would be.

In July 2019, the last date with available data, ICE held 55,654 people in its detention centers, of which 8,802 were Cuban. In that same month, the Trump administration announced a measure that would be a severe blow to the asylum requests of immigrants from various Latin American countries, including Cuba: those who had not requested protection in at least one country through which they crossed on their way to the United States would be denied asylum.

This also applies to Cubans, as Mauricio Claver-Carone, Donald Trump’s former special adviser, clarified. “The United States is not the only place where they would be safe. We think that they would be safe in Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador or Mexico, so our main interest with Cubans is that they are safe, that they are not persecuted by the regime, by the dictatorship in Cuba and we feel that in these transit countries they could ask for asylum,” said the official.

The measure is part of the context of nearly 400 executive orders issued by the Trump administration that have radically changed the immigration system in the United States. They record a chronology of actions with a clear anti-immigrant orientation.

As a result of that orientation, according to Barbara Hines, an American immigration rights attorney and founder of the immigration clinic at the University of Texas School of Law, America’s asylum system was systematically downgraded. For the specialist, although migration policies that imply human rights violations did not begin with Donald Trump, “under his government, they reached previously unknown dimensions, within the framework of an expansion of xenophobic and anti-immigration discourses.”

Stewart’s immigration court has one of the highest deportation rates in the United States. In 2019, 87% of asylum cases were denied.

The deportation of Cubans from the United States, which for decades was not accepted by the island’s government, found a way as of 2017, with the end of the “wet foot-dry foot” policy at the end of the Obama administration. Along with this measure, which overturned the immigration facilities that Cubans had enjoyed until then upon their arrival in the United States, an agreement was established through which Cuba agreed to receive a group of almost 3,000 deported Cubans who had emigrated to the United States through the port of Mariel.

The Cuban authorities conditioned the expansion of this initial group to a case-by-case detailed analysis, to which they must respond within a period of 90 days. Meanwhile, fear spread among Cubans who sought to regularize their immigration status in the United States, who now saw deportation as a viable possibility.

In 2019, there were an estimated 39,000 Cubans with deportation orders. That year, 1,179 were deported, a 600% increase since the agreement began. For many, the flight ended the immigration limbo that implies not being able to access a life as residents or citizens in the United States, nor to return to their country of origin. For others like Yosvel, who have already signed their deportation orders but are still in detention, limbo has turned into hell.

Life on screen

Yania says that her family is aware of Yosvel’s situation in Stewart not only because of his calls, but also because they maintain communication with the organizations that assist them and with relatives of other Cubans in the same situation. “This is how we learn things that he doesn’t tell us because he doesn’t want to worry us anymore.” She is referring to Yosvel’s asthmatic attacks, about which they have heard from the relatives of other detainees.

That and other sufferings are not on one side of the screen. In Cuba, Yosvel’s family languishes.

“Every time I go to the doctor with my mother, because of her illness, they also tell her that she has nervous problems, because she always has high blood pressure and constant concern for him,” says Yania. She clarifies that Yosvel is the only male child and that he always lived with his parents.

Yania is 42 years old, married and the mother of two children: one is 20 years old, a law student, and the other is seven, who is in primary school. She suffers from Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, a heart condition that causes arrhythmias, palpitations and dizziness. Her father, Edel Ferrer, 74, has been bedridden for 19 years due to a stroke that affected his communication and motor skills.

“I’d like you to see how my dad gets when Yosvel asks to see him on a video call,” she says. Although my father doesn’t speak or walk (he is bedridden), he does know him and sees him, and that affects him. All that makes me worse too, because I’m seeing how he is there and my parents here suffering.”

Yania says that the worst part for her family is uncertainty; not knowing when Yosvel will be released or under what conditions. “Everything that has happened is very unfair, because he hasn’t committed any crime, he just wants to work. He didn’t even sneak into the United States; he surrendered, voluntarily presented himself to comply with the legal mechanisms that were established. He trusted that the situation would be different, and it was all a hoax.

“If they won’t accept him there, then let them return him, since here he has his home, his family. He will have trouble getting a job, but at least he would be healthy and with us. And if they are going to release him, then they should release him; he also has family there, who are responsible for him. In addition, he is a professional, willing to work and he will not be a burden. But the thing is that they don’t make any decision, neither here nor there, and he continues to be locked up and in need,” she adds.

They just want to see him free, in Cuba or in the United States. Yania knows that this unites her with many other families. “I defend my brother because he is my brother, but I think of all those who are going through this, which is terrible, and also of their families. I wish they could all could solve that situation, because they can be good and innocent people just like him, who just want to get ahead in the United States. They are doing a great injustice to them; it is a question of humanity,” she concludes.

Ariel Pérez Álvarez’s voice trembles as he recounts that he has been at Stewart for more than a year and a half. In the video, with a delay in the sound and occasional loss of connection, which makes it difficult to understand some fragments, the words “despair” and “lie” can be clearly heard. “They tricked us with parole, they tricked us with bail,” adds another detainee.

The end of the Trump administration and the transition to the Joe Biden administration, while raising hopes for a change in immigration policy, could slow down the ongoing processes.

“We want them to release us or deport us to Cuba.… They are going to keep us here, I don’t know for how long or how,” says Ariel. With a gesture of despair, he hands over the headphones to another detainee who, from behind, tried to help him present his case, seeing how words failed him.