Almost a decade after January 1959, the tension between heterodoxy and orthodoxy would be one of the distinctive features of the Cuban landscape. 1968 was a key year in that sense.

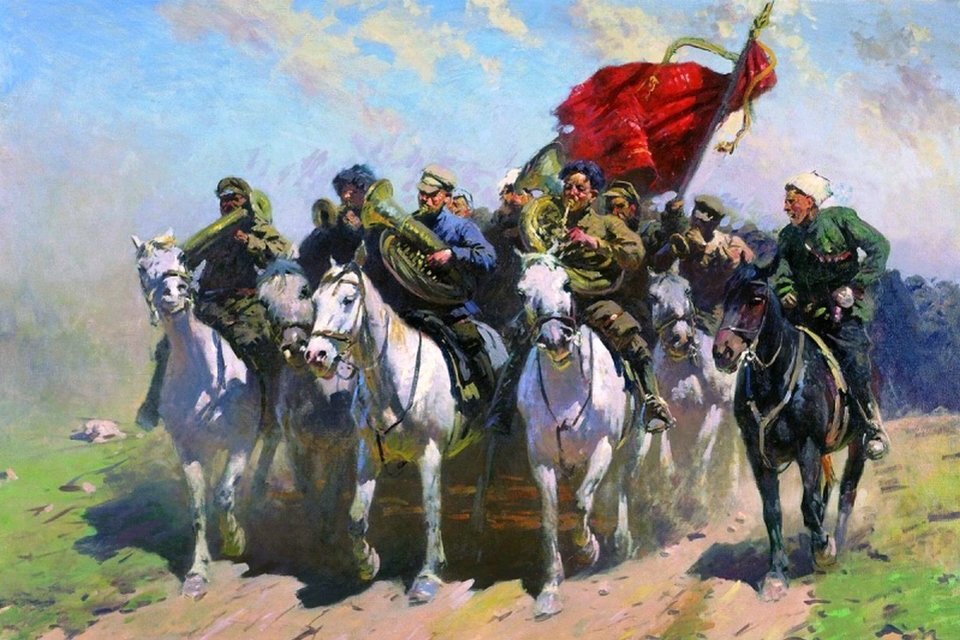

Precisely because of its heresies, the Soviets viewed the Cuban process with distrust and suspicion, or at most as it was from the very beginning: a task of some petty-bourgeois bearded boys who had to be guided along the true path. Guerrilla focus vs. mass struggle. Voluntarism vs. centralized planning. Socialist realism vs. plurality. On this last point, in “Socialism and Man in Cuba” (1965) Che Guevara had written against any possible tropical Zhdanovism:

In countries that went through a similar process [he refers to those of Eastern Europe, A.P.], attempts were made to combat these tendencies with exaggerated dogmatism. General culture became almost a taboo and a formally exact representation of nature was proclaimed the summum of cultural aspiration, later becoming a mechanical representation of the social reality that was wanted to be shown; the ideal society, almost without conflicts or contradictions, that they sought to create….

So simplification is sought, what everyone understands, which is what officials understand. Authentic artistic research is annulled and the problem of general culture is reduced to an appropriation of the socialist present and the dead past (therefore not dangerous). This is how socialist realism was born on the basis of the art of the last century.

Concluding the following:

The intention is not to condemn all forms of art after the first half of the 19th century from the pontifical throne of fanatical realism, because it would fall into a Proudhonian error of returning to the past.

At that time, something was happening in Cuba that almost nobody remembers today: the simultaneous construction of socialism and communism in three small rural towns: San Andrés de Caiguanabo, in the Guaniguanico mountain range, Pinar del Río; Banao, in Las Villas; and Gran Tierra, in the East. A concrete way of positioning oneself against orthodoxy and an expression that utopia was attainable by other means, far from any Eurocentrism. “Naturally,” a scholar observed, “in that attempt at communism the State did not cede its functions to society, but on the contrary, it concentrated all of them.”

On the other hand, according to Raúl Castro, towards the end of 1967 the Cuban leaders had in their possession “information coming from various sources, all of it reliable, which led us to suppose the existence of a current of ideological opposition to the Party line…. This current did not come precisely from the enemy ranks, but from people who moved within the ranks of the Revolution, acting from supposedly revolutionary positions.”

That is what explains the arrest of more than 30 former militants of the Popular Socialist Party, led by Aníbal Escalante (1909-1977), former lawyer of sugar leader Jesús Menéndez, former editor of the newspaper Hoy and member of the Central Committee, who in 1962 had been relieved of his duties in the process of formation of the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI) during the fight against sectarianism.

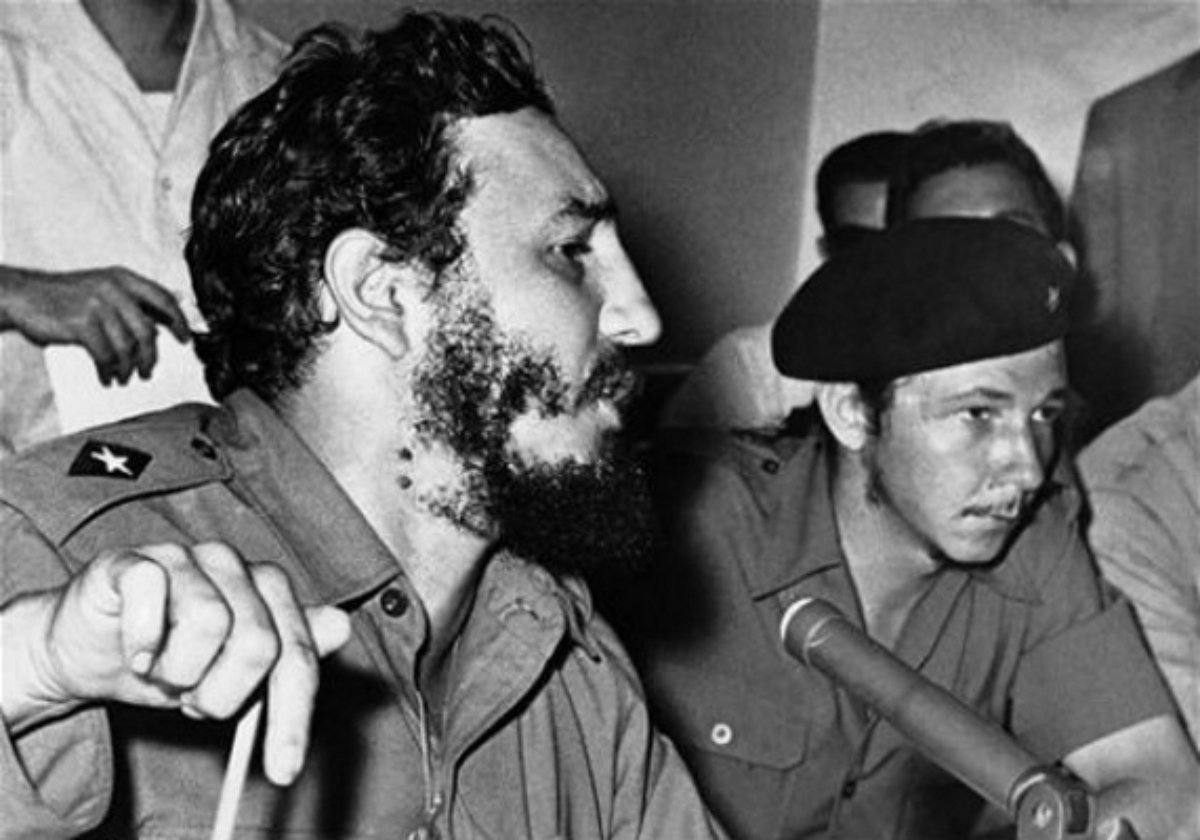

The process against the microfraction was underway in January 1968 while Fidel Castro was speaking to the intellectuals at the closing of that Cultural Congress in Havana. The micro-fractionalists’ list of objections and criticisms of the guerrilla fighters of the Sierra Maestra were practically the same as those of the Soviet officials: from economic issues such as the lack of knowledge of the law of value and the budgetary financing system, to the excess of volunteer and unpaid work. Nor were the problems of foreign policy left out, especially support for the guerrillas and the training of Latin American combatants in western Cuban mountains.

Two months later, in March 1968, on the university steps on San Lázaro and L streets, Fidel Castro would speak out for the second time against the Soviet manuals, in a position in keeping with the young professors of the Department of Philosophy of the University of Havana, also creators/editors of Pensamiento Crítico (1967-1971), one of the magazines that summarizes the spirit of that entire period.

He then alluded to the “abyss, the enormous abyss that sometimes mediates between general conceptions and practice, between philosophy and reality.” And he also said: “the manuals have been getting outdated, they have been becoming something anachronistic, because they are not capable of saying a single word on many occasions about the problems that the masses should know about.”

Backed by the Warsaw Pact, but opposed by Romania and Albania, on August 20, 1968, the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia. On Friday, August 23, three days after the tanks entered Prague, Fidel Castro made a television appearance in which he supported the action: “We accept the bitter necessity of sending forces to Czechoslovakia and we do not condemn the socialist countries that made that decision,” he said.

Obviously a change, but:

We wonder whether in the future relations with the communist parties will be based on their positions of principle or will continue to be dominated by unconditionalism, satelism and lackeyism and will only be considered friends those who unconditionally accept everything and are incapable of absolutely disagreeing with anything.

And with several additional questions, all provocative:

Will the divisions of the Warsaw Pact also be sent to Vietnam if the U.S. imperialists increase their aggression against that country and the people of Vietnam ask for that help…? Will Warsaw Pact divisions be sent to Cuba if the Yankee imperialists attack our country, or even, in the face of the threat of an attack by the Yankee imperialists on our country, if our country requests it?

The famous “critical support” that scholars of the period speak of. “The KGB believed that Castro would support the protest movement of the Czechs to score points against the USSR, but to its surprise, the Cuban leader condemned the liberalization movement” [of the Czechs, the Prague Spring, A.P], a Russian academician wrote.

Not only the KGB but also national public opinion. Testimonies of the time assure that the people in the streets expected a condemnation of the invasion due to certain obvious similarities: a small country saw its sovereignty violated by one that was too big. There was indeed a current of empathy towards the Czechs, not only for being heretics and tots, but also for their films — for example, the musicals Vals para un millón and El amor se cosecha en verano or the parody of the Old West in Lemonade Joe —, for the rock and jazz records that were sold at the Casa de la Cultura Checa, on 23 y O, and even for a beer tavern located at San Lázaro and N streets.

But the arrow had been thrown. The hour of institutionalization was already arriving.

To be continued…