Ernest Hemingway found inspiration for some of his works in themes, characters and details in the books of Cuban author Enrique Serpa, according to a new book about the friendship with Cuba of the writer of The Old Man and the Sea, authored by U.S. researcher and professor Andrew Feldman.

Feldman said to EFE in Miami that he didn’t think Hemingway stole Serpa’s stories, because there is a clear difference between their works and they have their own styles, but he thought the influence is sufficiently visible to ask to what extent their friendship and intellectual exchange affected Hemingway’s works.

Ernesto. The Untold Story of Hemingway in Revolutionary Cuba (Melville House), which will be released this Tuesday in the U.S., is the result of an investigation carried out by Feldman on the island following orders from the 1954 Nobel Prize for Literature: If you want to be a writer, you must be able to “walk in the shoes” of another.

Feldman was fortunate to be the first foreigner to have access to the archives of Finca Vigía, Hemingway’s home on the outskirts of Havana, now converted into a museum, and he remained in Cuba from 2008 to 2010.

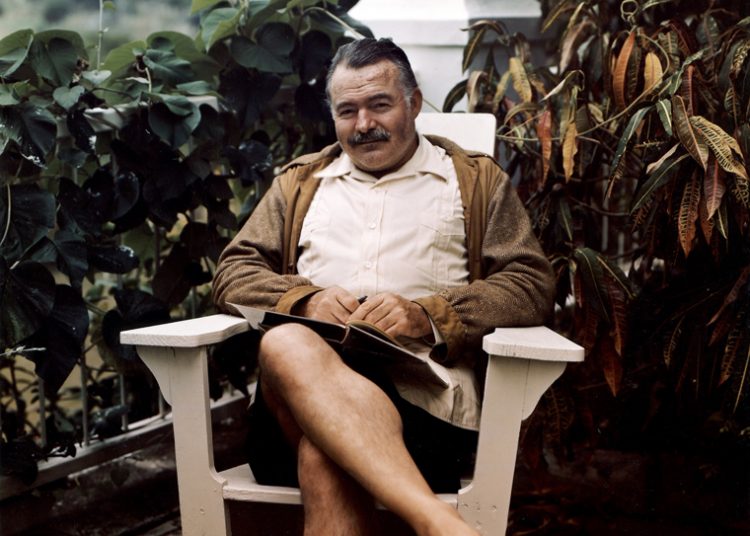

The main theme of the book is Hemingway’s relationship with Cuba, a country he visited for the first time in 1928 and in which he resided in the 1940s and 1950s.

Feldman, who recalls that when Hemingway received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954 he defined himself as a “citizen of Cojímar,” a municipality a few kilometers from Havana, said he developed a genuine empathy, respect and friendship with the Cuban people.

In the interview with EFE, Feldman stressed that when the Revolution triumphed in 1959, the U.S. government told Hemingway he had to denounce it and leave Cuba, but he did not do it because he said his job was to write, not politics, and because Cuba was his home and the Cuban people were his friends.

One of his Cuban friends was Enrique Serpa (1900-1968), winner of the Cuban National Prize for Novel in 1938 and whom Hemingway considered a “prodigy,” according to Martha Gellhorn, the writer’s third wife, in a letter to his editor, Max Perkins.

Feldman says it would not be “fair” to say that what Hemingway did with “Aletas de tiburón” and “La aguja,” two works by Serpa which had a “notable influence” on The Old Man and the Sea (1952), was plagiarism.

He said it would be difficult to identify an artist worthy of praise who has not found inspiration in other works of art.

In his opinion, Hemingway did not “copy” Serpa, but learned a lot from the stories of the Cuban, who had a talent comparable to his and “a very elaborate, powerful and expressive prose.”

After reading both carefully, Feldman still wonders how it is possible that Hemingway became so famous and rich throughout his life and Serpa died relatively unknown and earning very little for his work.

The researcher and his wife, Yelani Reyes León, a Spanish teacher in New Orleans, intend to do everything possible to ensure that Contrabando, Serpa’s major work, is translated into English and published in the United States.

Leopoldina Rodríguez, an educated mulatto woman, with a hectic love life, was another important influence for the author of For Whom the Bell Tolls, who made countless references to “Leo” in his letters and created a character in Islands in the Stream, “Honest Lil,” clearly inspired by her.

Among the lovers of this courtesan who spent time in Spain and frequented Havana’s El Floridita bar was Spanish Falangist leader José Antonio Primo de Rivera, executed by firing squad at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Hemingway wrote in a letter.

Hemingway and Leopoldina made each other company and were friends during the most difficult days of his last years. They taught each other about their cultures of origin. They became close friends. They took care of each other in a way that others did not, says Feldman.

The author of Ernesto… was very interested in the fact that Hemingway took the medal of the Nobel Prize to Our Lady of Charity of El Cobre, Cuba’s patron saint, in whose sanctuary it is still on exhibit along with those of the Cuban military and athletes.

Feldman says that Leopoldina seems to have had an influence on the writer’s religious practices, as well as helping him understand and appreciate Santeria, folklore and other elements of Cuban culture.

Hemingway paid the rent of Leopoldina’s apartment in Havana for many years and when she died of cancer in 1956 he was the only person who attended her funeral, according to Norberto Fuentes, the Cuban biographer of the U.S. writer.

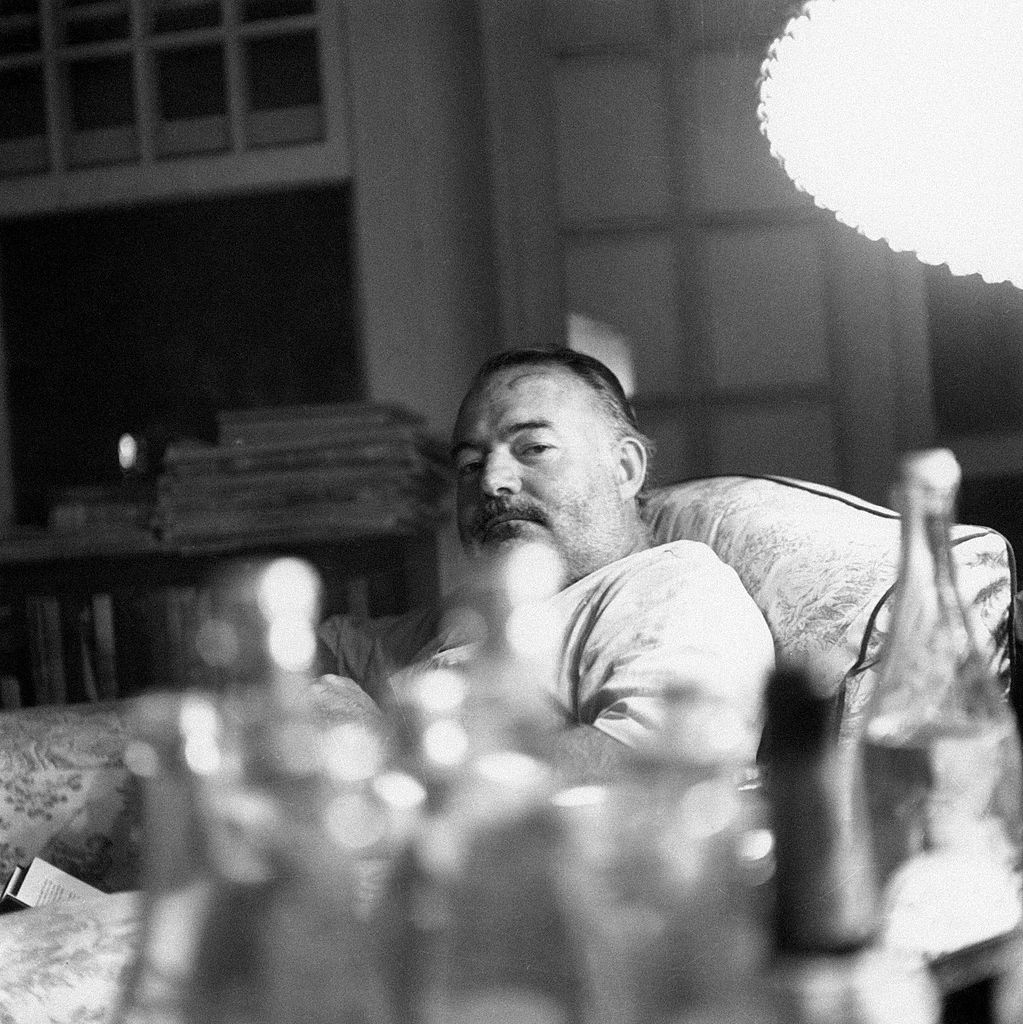

If Feldman is asked why the interest in the life and work of Hemingway has lasted for almost 60 years after his death, he replies that he is “one of the most perceptive and expressive writers” of the 20th century and he knew how to create “a myth around himself.”

Feldman concludes by saying that he thinks Hemingway is a kind of literary superhero who shows us what we are capable of, and that in the tradition of Daniel Boone, Paul Bunyan, Perseus, Achilles and Ulysses, he became bigger than life, half man half immortal, a demigod, who seemed to transcend the limits of a single life.