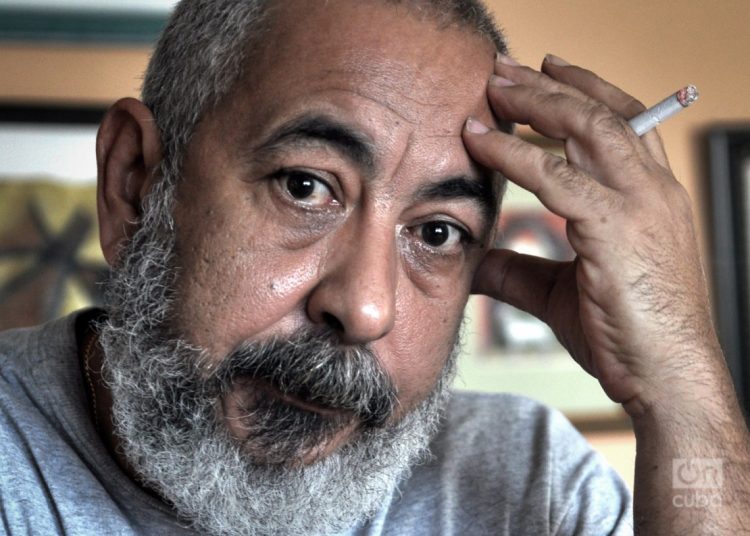

Leonardo Padura regrets not being Paul Auster. Not so much for the work of the American writer, whom he openly admires, but because, unlike him, journalists rarely ask him about literature during the long and intense promotional tours of his novels: they are generally more interested in knowing how he lives in Cuba (and why he remains on the island) than about his literary creation and aesthetic affiliations.

His statements, often used out of context, if not full of mistakes, are always controversial on both sides of the ideological and geographical sea that separates Cubans. On other occasions they appear as they are, and also put people’s backs up. In two words, and paraphrasing a famous montuno, “no matter what, you have to give your opinion.”

I “reached” him in Bahia, Brazil. He has just arrived from the International Book Fair in Lima, where he was as a special guest. There he presented the volume of essays Agua por todas partes. A long journey in this country awaits him; he will give lectures as part of the “Fronteiras do Pensamento” cycle and promote the Portuguese edition of La transparencia del tiempo, his most recent published novel, which already circulates, in the corresponding languages, in Spain, Portugal, Germany, France, Italy and Denmark, and, as usual, still has no date for coming out Cuba.

Padura has been following the national sport, its splendors and downfalls, practically ever since he can remember. Therefore, in these summer days of baseball disheartening, that is what we talked about.

Are you abreast of the performance of our baseball team in the Lima Pan American Games?

I didn’t see all the games, but I know about the disaster. The most resounding of the last 150 years. I am not surprised by the results. They were doomed to not win. But, as you can always do more, they made an effort to lose shamefully. In recent years, the Cuba teams have been shameful. And this time Anglada’s made people want to cry, because he wanted to win more than the others.

Did you think that Rey Vicente Anglada was going to reverse the results of the Cuba team in its latest international presentations, in a nose-dive since 2002?

Anglada is not a magician. No manager is. A good manager helps a team grow, but no one can revive a dead person. The “Anglada solution” was taken from above, by those who know, but those who know so much forget that the problem of Cuban baseball is not the players, but a system that no longer functions in the sports, the economic, the social fields. Today the only incentive Cuban players have is that they be hired in a league abroad, and it is logical that it be like this, since they have only one life and a very short career. These players who have lost their sense of sport and are thinking about their own lives, their future and, above all, their present, are now fleeing from the image of a great Cuban baseball player from the 1980s-90s who ended up collecting slop on a bicycle for the pigs he raises.

Many things are agonizing in a country that has lived in crisis for 30 years. For example: what is happening to current Cuban novel writing? Does any writer really want to publish in Cuba and assumes it as a success in the same way as in the 1980s, when we won all the baseball championships and when 5,000 pesos and a national prize for a novel meant something? And with music? And with agriculture? And so many possible etcetera. Cuban baseball’s defeats are not a cause of anything, but the consequence of many things that affect Cuban society and whose solution has been postponed as if time didn’t go by for people, for the country, for the world.

Then, it’s not possible to talk about Cuban baseball without referring to politics?

No, it’s not possible, because in Cuba all decisions that are not the most personal (and sometimes not even those) go through politics. In our case, sports was politicized, in the same style as the Eastern European socialist countries. It became part of a war of systems. And it was supported as an achievement of the system. But politics haunts us even from other areas: the cancellation of the agreement between the Cuban Baseball Federation and the MLB was a political decision of the U.S. government. Baseball, like everything else in Cuba, has been affected by the powerful neighbor’s practices towards the island and that is something that cannot be ignored. This is added to our own mistakes and orthodox political decisions, such as treating as traitors the athletes who left Cuba however they could, and who then even disappeared from the list of players with a remarkable record in the country.

On TV a commentator said that now a symposium or something like that is necessary where the situation of our baseball is debated, that opinions must be heard….

That symposium would not be bad. Things that are being repeated for a long time would be said there. But will there be a will to hear them? And, will hearing them make it possible to make some changes? Cuban baseball’s solution is in sight: create a professional league. Now then, would the island’s economy support it? Of course not. Is it politically desirable? I don’t think so either. So why talk more?

They say that all Cubans are managers of the Cuba team. If so, what would be your most drastic decisions?

To resign! I would also do it if I were the coach of the soccer team.

Many assumed that we would recover the great prestige that our national sport had. Looking back without nostalgia, were we really that good in the past?

There were times when, except for five or six players who were active in MLB (Luis Tiant, Tony Oliva, Tany Pérez), the Cuba teams were formed with the best players born on the island. And those teams, neither before nor ever, have played against the best possible teams from countries such as the United States, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Dominican Republic…. And it happened, in addition, that those were years in which the country gave a couple of generations of very talented players: from Marquetti, Capiró, Vinnent, Rogelio García, the two Sánchez and Changa Mederos, to the time of Omar Linares, Kindelán, Pacheco, Tati Valdés, Duke Hernández, Lazo, Vera, Germán…. Today the national team doesn’t have a single player of the quality of those that I mentioned, randomly, from a list that could reach 50 names without lowering the quality much.

It never rains but when it does it pours. The special period began in 1989, then the drain of talents, the entrance of the professionals in the international championships and the development of techniques closely linked to the digital revolution. We fell behind in everything. In a country where for years we had no outside information, it was difficult to advance at a pace of development like the one lived today. We will pay for a long time for our lagging behind in various fields, such as access to information through new technologies.

On the other hand, the fact that we seemed so good made sports, not just baseball, be permeated by a spirit of championism that was guaranteed with selective, high performance sports. Where do you play baseball, basketball or volleyball today in Mantilla? Nowhere! And that happens not only here in the capital, but also in all the provinces. Even so, as by divine work, quality players continue to emerge among us, we don’t even know some of them, since they emigrate when they are teenagers.

You said “here, in the capital.” Aren’t you in Brazil?

Cuba is always here, my here. It doesn’t matter where I am. Now on the island everyone wants to be a soccer player. And that’s very good. Perhaps the team that went to the Gold Cup and lost enduring 14 goals without scoring any is better than the baseball team that allowed nine homeruns in an inning of a game that it was winning with an advantage of eight.

From where do you get your love of baseball?

Baseball has been in my life since before I was born. My father dreamed that his firstborn, who turned out to be me, was male and left-handed, so he would become a baseball player, and could achieve opportunities in the field that he did not have given that he had to work every day since he was very young. That’s why in my newborn’s crib there was a ball. In one of the first photos I have, when I was barely taking my first steps, I’m dressed as a baseball player. Of course, it was an Almendares uniform. Alicia, my mother, sympathized with the Cienfuegos team and Min, a very close uncle, was an all-out Havanaist. That fragmentation of loyalties was typical in the Cuban families of those years.

When did you start playing?

Before I was five years old; with my friends in the neighborhood, in a plot of land that was on the corner of my house, where the bakery is now in Mantilla, my neighborhood of then and now. My father had taught me to pitch, field, bat, but I think the rest I learned on my own. In Cuba one learns to play ball by playing ball, learn about baseball by living it every day: it’s such an intimate cultural relationship that it doesn’t need intermediation.

Then, when I was a few years older, three important things happened in my life, related to baseball. The first and most dramatic was that in 1961 my father stopped following baseball. Like that, overnight. It was the time in which the elimination of professional sports in Cuba was decreed and, consequently, the old baseball clubs disappeared and new ones were founded, revolutionarily made up with amateur players. I remember that my father made an effort in the middle of his inability to understand what was happening (how can one live without the existence of the Almendares, or the Habana, or the Marianao, or the Cienfuegos teams?) and took me one day to the stadium in Havana. I have a flash of memory, and I know it’s true because I remember nothing short of the moment when a player named Rigoberto Rosique entered the batter’s box. Wow, I can see it right now if I close my eyes. My father didn’t go again until I ordered him to do so again in the 1980s, more than 20 years later, 20 years in which the man who suffered and enjoyed every game of the Almendares hadn’t seen a single organized baseball game.

Another important fact of my relationship with baseball was that my uncle Min didn’t give a damn about any of this and, when the baseball system in Cuba changed, he kept watching baseball and going to the stadium, to any stadium, and since he had no sons at that time, well, he took me to see baseball almost every day in his brown and white car, I think it was a half-broken-down Buick. That’s how I learned about the Cuban baseball of the 1960s.

And the third fact?

When I was about 10 years old, my father went to talk to Fermín Guerra, the great catcher, to ask him to include me in a kind of academy there was in a sports field near my house. My father knew Fermín, and admired and drooled over him, not only because he had been a great player, but also because he was a Mason, like him. And from the hand of that legend I learned from the inside, really, what baseball was all about.

I still have a memory of those days in that sports field of a lefty, whom Fermín personally attended and said that if he learned to throw strikes he would be the biggest pitcher in Cuba. The boys his age called him Changa. His name was Santiago Mederos and he was one of Cuban baseball’s greats.

How were you as a player?

I was always more skillful and intelligent than good as a player. But as I have always been so stubborn, I made a great physical effort, and played a lot in impromptu tournaments and also in some official ones, up to the provincial level. Since I was left-handed, I played in first base and in the fields. But the first baseman needs a player of greater height and stronger at bat, and that’s why he couldn’t advance much by that means.

But even with those limitations you formed part of the teams.

What happened was that at that time baseball was played so much and in so many places, that even the worst players had a space, and I exhausted that space until I was 20 years old, when I played in the University and in some neighborhood tournaments in my area.

I remember a game with the Philology Tigers, a frankly unfortunate team, in which you hit 3 out of 4. It was memorable especially because a fly ball fell on the fielder’s head. I think his surname was Cicero.

At the University I started writing, and to hell with the Sundays dedicated to baseball. Can you imagine the earthquake that was for me, the discovery of literature, which managed to separate me from practicing baseball?

Since when do you follow the Industriales?

I think I’m an Industriales fan since 1963 or 1964, when the team was just created. It was, somehow, the heir club of the Almendares, and many Almendares fans, since they were baseball fans, immediately became fans of the Industriales, and that happened not only in Havana, but throughout the country.

Who were your idols then?

I soon became a fan of several of those wonderful players of the 1960s, some guys who didn’t have great technique, were not the best players in Cuba (the best had professional contracts and could not play again in the Cuban championships, which were only for amateurs) but they were the beings with the biggest desire to play ball that I have seen in my life: they played, really, to play, they competed to compete and that made them special. Of those players my absolute idol was Pedro Chávez, but also Tony González, Urbano, Manolito Hurtado, Ricardo Lazo…and then two players from another generation but who were spectacular: Marquetti and Capiró.

In those 1960s I used to play ball all the time. There was a school grade in which I had 66% attendance at classes and, according to my mother, she sent me to school every day. You can imagine what I was doing. And in classes I drew ball fields, made up teams. At home, I cut and pasted photos and box scores in a notebook. When I ran down the street, I imagined I was running the bases in a baseball field because I had decided a game. I ate and shit baseball.… Because I had become a “baseball addict”! as it was called at that time. Of all my classmates, I was among the most addicted, along with Jipi el Polaco and his brother Ale el Burro, Danilo el Gordo and Rafelito el Cojo. We were the worst. All, in addition, furious fans of Industriales.

Did you only go to the Latin American Stadium?

With those and other friends I started, I think when I was 9, 10, to go only to the Latino. Since my father didn’t take me, I had frequently gone with my uncle Min, but no way, going with my friends was the best! That group also included Jorge Luis el Conejo, el Gordo Montes de Oca, el Negro Pello, Manolo Palacios…. Wow, remembering this affects me. Imagine, out of all those people only Ale el Burro and me stayed in Mantilla, and every time we meet (almost never) we start talking about baseball….

Going to the Latino, at that time, was not only an act of sports faith, but a kind of border that was broken: one started being a “little man” because they let you go there alone and you had to take one or two buses, and return home very late. I swear it was never again the same: because of what it meant spiritually and because of what it offered me in sports…. If I make an effort, right now I can remember several games, with protagonists and everything: Julio Rojo, Rigoberto Betancourt, Changa Mederos, Eulogio Osorio, aka Cara de Vieja…. I remember even the blonde who was Tony González’s girlfriend and sat on the third dugout!

Referring to baseball, what is the difference between a fan and an aficionado?

I was a real baseball fan, at a time when I don’t know why, I think it was because of the revolutionary rhetoric, it was more elegant to be an aficionado. It was a matter of degrees, and I think I still feel this way: the fan is someone who likes a sport. The fan is like me, an addict who lives the entire damned day thinking about that sport.

I’m still an Industriales fan because, as Manuel Vázquez Montalbán said, one can change many things in one’s life: country, woman, political party, but never a fondness for a sports club if a sense of belonging was acquired as a child. And I’m a fierce Industrialista. Although increasingly less fierce, really, because I don’t go to the stadium anymore or follow the championships too much; I don’t like what I see in the field. It’s a baseball that does not look like the one I enjoyed in the 1960s, the one I saw later in the following years, until the 1990s, when everything started to fall apart because the world changed and people changed and Cuba did not change and…the ball game went to hell. I have written and thought about that, so I stop here. Damn it, what I would have given to be a good baseball player!

The National Series is about to begin. What do you expect from the Industriales?

Let them do what they can. In a baseball whose qualitative levels are as unfortunate as the national team demonstrates, anything can happen. All this makes me very sad and makes me think of the person I was in 1967, who cried, and a lot, when Alarcón’s Orientales beat the Industriales in a memorable series. Then we loved both baseball and even Glenda, not Torres, just Glenda, the one in the English movie, when going to the movies, like the stadium, was also a party.