In his new novel Como polvo en el viento, Leonardo Padura (Havana, 1955) narrates, through constant and temporary vertiginous ups and downs, the story of El Clan, as he calls a group of friends formed in the Cuban capital during the 1980s. The house of one of them, Clara, which for the author embodies “fidelity, love and permanence,” is the base and turning point of the different destinies of the characters and that mostly pass through the exile.

The generous historical context and the disparate way in which each one of them assumes his condition of exiled, from Irving’s incurable nostalgia (“romantic, patriotic, irreverent,” according to Padura) despite falling in love with his new host city, Madrid, to the clean slate of the most radical of all, Elisa (“for her a single adjective: terrible”), give away a deep and addictive reading, the result of more than two years of research work and trips to the scenarios where the story unfolds, from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Tacoma (Washington), passing through Madrid’s Parque del Retiro, Barcelona’s Ramblas or the Tarragona summer enclave of Segur de Calafell.

“Como polvo en el viento”, una novela “muy visceral” de Padura

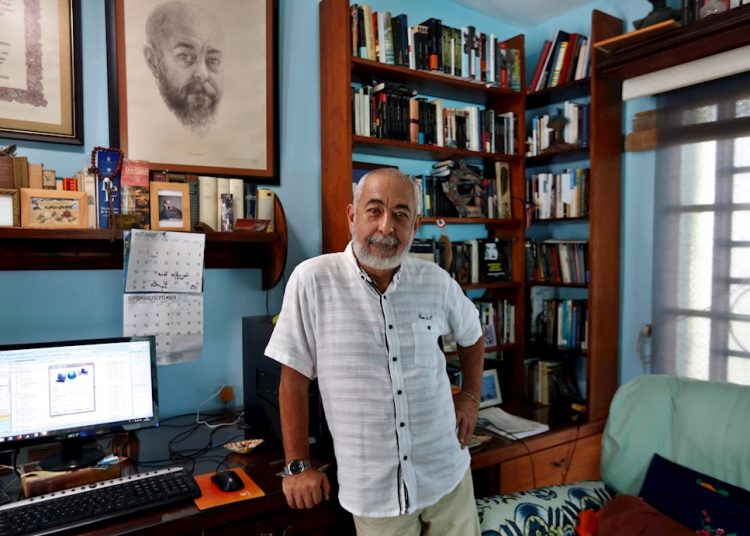

EFE interviewed Padura in his home, an apartment full of plants, art, recognition and memories on the humble second floor of a shared house in Mantilla, the Havana neighborhood that saw him grow up, also as a writer.

Since Como polvo en el viento is already available in Spain (Tusquets) and in the coming weeks it will arrive in bookstores in Latin America, Padura has already received the first impressions of readers in Cuba because, he confesses, a pirated copy in PDF circulates unstoppably on the island.

This doesn’t seem to bother you….

Here in Cuba it doesn’t bother me, because it would inevitably happen, next week or next month. I myself often consume literature that comes to me through alternative means, because there is no book market in Cuba; there are publications and they are very depressed at the moment. My previous novel, La transparencia del tiempo (2018) has not yet come out here.

Could it be that what is said about Cuba in the novel bothers someone?

My books usually annoy a lot of people and they satisfy a lot of people too, and that’s part of the literature game. You write what you believe, what you think, and you abide by the consequences. Literature is not to achieve consensus; it’s about reflecting a reality and there may be assessments that certain people don’t find pleasant. I always say that the truth is relative. However, the lie is absolute. And in my book there are no lies.

The characters in the novel assume and experience exile in different ways, from permanent nostalgia to the reneging of their past. Are there more dignified, valid, honest or coherent ways of facing the condition of exile than others?

No. All people’s options are valid, as long as they don’t attack other people. If the decision of one becomes the detriment of another, there is already an ethical or political conflict. In the case of how to face exile, there is no possible reading: exile always involves uprooting, even when assumed in the best way, when you are doing well economically, when you feel emotionally satisfied.

In the book the most radical positions are criticized or satirized, of people who live in exile with hatred, for example

I don’t like radical postures at all. I’m a heterodox, and as a heterodox I doubt; I have no absolute certainties. I think that you can always review what you think, what you feel, and understand it differently at certain times. Extreme positions, no matter how well founded they may be, always have an element that terrifies me: the exclusion of the other: if you take a position that doesn’t allow dialogue, you exclude the voice of the other. How are you going to tell me that your God or your political party is the only one, that if I don’t believe it the way you believe it, I’m excluded, condemned, lost.

You never wanted to emigrate. If you had emigrated in the years of your youth, as the characters in your novel did, which one would you have identified with the most?

The character with whom I identified my possible position with exile is with the character who arrives in Madrid, a gay man, although I’m not gay, up until now (laughs). He carries a series of belongings, of relationships. It’s not the same to leave without leaving anything behind than leaving everything behind. And that’s an element that roots you in a certain context and reality. That’s why that character, Irving, tries to create a routine to adapt to life in Madrid, but that routine is always permeated by absence, distance, remoteness and the feeling that he is no longer who he had been.

Do you have to be Cuban to fully understand what happens in Como polvo en el viento?

My plan was that it not be a novel only for Cubans: I believe that if you write for such a specific public you are reducing the space of literature. Unamuno said: we have to find the universal inside the local and, in the limited and circumscribed, the eternal. That’s a lesson that I learned a long time ago. In this novel and in The Man Who Loved Dogs, everything leaves Cuba and returns to Cuba. And I try to make these conflicts universal. I believe that uprooting is a universal conflict, belonging is a universal behavior.

The concept of homeland is omnipresent in the novel, as it is in Cuban idiosyncrasy. For you, what is the meaning of homeland?

I recently read from a Cuban writer in exile that the homeland is an invention of the romantic poets, but they didn’t take bureaucracy into account. Bureaucracy somehow appropriates everything, including the sense of homeland. I believe that the homeland is that place with which one identifies sentimentally, spiritually, culturally. It has no replacement because that identification is permanent, it makes you who you are. You can be a cosmopolitan, have a very universal vision of the world and live anywhere, but you belong to a place. When they ask me, why haven’t you left? Why do you stay in Cuba? I answer that I stay because it would be very difficult for me to be anything other than a Cuban writer.

Is loving one’s homeland, being a patriot, necessarily a virtue, a duty?

Love of country is a laudable attitude, necessary, because you are ultimately loving yourself, your ancestors, those who are going to be your successors in that context. Here is an issue that can be complicated, what is the state, the nation, the homeland…. I think the homeland is above all that and enters a territory more of feeling than of the legal. What is legal is the state, the nation is a sociocultural, historical creation, and the homeland encompasses all that.

The concept of statelessness, as taken from your novel, has negative connotations and is even an insult in Cuba. Is it necessarily bad?

The way it has been used has a pejorative charge. There is a legal or administrative application of your condition of belonging or not to a country, and that is related to something bureaucratic, which is citizenship. Until ten years ago the migratory figure of “definitive departure” existed in Cuba: you left Cuba and lost all your rights and your citizenship except when you wanted to return, when you had to get a passport and a permit to enter. It could be quite wounding having to become stateless.

Como polvo en el viento draws a Cuba in the 1990s and 2000s where a single thought is imposed by force, those who think differently are repressed, poverty reaches a large majority of the population and corruption spreads in all levels. To what extent has this changed?

Cuba’s persecution is very complicated, because by not changing the political-economic system, it gives the impression that Cuban society has not changed. I believe that in 1989-91 there was a very deep cut in social evolution. At the beginning of the 1990s, the euphemistically called special period begins, a very deep economic crisis that caused a very deep social crisis. We’ve not left neither one nor the other. We continue to drag consequences and the presence of these crises. In any case, that crisis has caused a change in Cuban society.

Your work describes how extreme social control, repression and corruption of a political system in a specific historical time deforms the destinies of the characters or destroys their lives. It also raises whether or not it’s really worthwhile looking for guilty parties.

If you get stuck in the search for guilt, you often don’t move forward. Forgiving doesn’t imply forgetting; forgetting is not the solution. Forgiveness is stepping over an offense or assault that occurs and moving forward. I believe that it’s necessary to have that perspective of being able to move forward without forgetfulness being what causes that stain, but the conscious attitude that we have to build, not run aground and destroy.

Does the group of idealists and intellectuals that make up El Clan represent the Cuban youth of the time?

My generation is the first in the world to go to university en masse, and specifically in Cuba. When I was studying, the only goal we had was to go to university. Over the years it has been changing. As of that crisis of before the 1990s, the university has become more selective: to get there you have to have special conditions of intelligence and material possibilities, because many times it depends on your parents being able to pay someone to review and prepare you for exams. My lifelong friends are cyberneticists, doctors, engineers, dentists, philologists as is my case, and it was not an elite group at all.

The characters in the novel of that generation also had very strong and orthodox ideological convictions. Compared to that how do you see today’s youth?

Our generation was very homogeneous since we had very similar experiences, behaviors and projections. That also breaks with this crisis of the 1990s. Today you find all the possibilities: from those who want to study to those who want to establish a business; those who want to stay and those who want to leave; those who think one thing about the system and those who think another. There has been a diversity of expressions in the new generations and what happens quite frequently is that the most prepared young people are the ones who tend to emigrate the most. That is a loss suffered by the country, the homeland as we said, and it’s very difficult to recover.

The novel provides a generous historical context: Obama’s name appears several times, but Fidel or Raúl Castro are not mentioned despite being inherent in the context. Is this deliberate?

That’s why, because they are inherent in the historical context. Yesterday they asked me what reactions certain names produced in me. Fidel? I said “omnipresent.” Everything that happens in our history is part of a process that was led and marked by the thought and figure of Fidel. What doesn’t need to be said should not be said. In the Cuban peculiarity, it’s necessary to know to what extent to advance in the explanatory or to let it be something that surprises in the reading itself.

In short… defeat after defeat, until the final victory.

So says a character in the novel named Bernardo, who brings the Kansas song “Dust in the Wind,” and he also repeats that of “defeat after defeat, until the final victory.” I owe the phrase to the friend to whom the novel is dedicated, Elizardo Martínez, a Cuban who went to Puerto Rico as a child and died two years ago. It left me a great void. I stole that phrase from him to give this feeling that, look, we always lose, but we are left with the hope that in the end we will win.

Excellent interview in almost every respect. Thoughtful and interesting questions and of course, Padura’s stimulating and insightful responses.

My only issue is with the quality of the translation, not so much its accuracy as it’s form. Eighty to ninety percent is just fine, but the rest is, at best, awkward and at worst unintelligible. It does a disservice to the intelligence of both interviewer and interviewee.

I’d suggest you consider having an english editor clean up translation where required.

But my appreciation overrides this quibble.