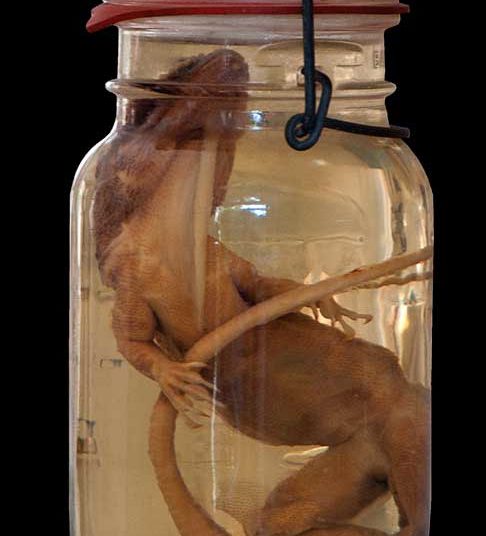

Photos: Darío Leyva

Many surprises await visitors to Fica Vigía, Ernest Hemingway’s former home in San Francisco de Paula, south of Havana, now a museum. One of these is the presence of a large chipojo lizard, or Cuban chameleon, preserved in formaldehyde in a large bottle in one of the house’s main bathrooms. When visitors ask why it is there, tourist guides and museum experts say that Hemingway once watched as that same lizard bravely defended itself when it was cornered by one of the farm’s many cats, until it succumbed to the feline’s superiority. Amazed by the lizard’s bravery, Hemingway decided to preserve it as a form of tribute to courage and dignity. This anecdote might seem a bit outlandish, but such an attitude on Hemingway’s part was coherent with his ethical principle, which he himself referred to as “grace under pressure.”

Hemingway believed that we all come into this world having lost the “fight” beforehand, because the simple fact of death was like a defeat of life; worse still, death can potentially wipe out the meaning of an entire existence. That is why he obsessively explored, exhibited and described diverse manifestations of grace under pressure in all of his work. For example, there is Francis Macomber the tourist/hunter in southern Africa who, despite the pain of seeing his beautiful wife cheating on him with the valiant professional hunter who is guiding them, finds himself anew in the act of hunting a wild buffalo, thus dominating his fear and recovering his trampled dignity, only to subsequently die violently and tragically — but redeemed in his own eyes — at the hands of his unfaithful wife.

Or old Santiago, in The Old Man and the Sea, who struggles first with an enormous swordfish and then, unsuccessfully, with the sharks that devour his prey. Hemingway seems to be telling us that a man can be destroyed but never defeated. Some have compared Hemingway’s code of ethics to the Bushido, the moral principles (or warrior code) of the Samurai. Actually, there are points of agreements, especially in the principle of respecting your rival and considering him or her to be an honorable opponent. However, Hemingway not only implemented this code for human behavior, but he also extended it to animals, either for behavior between animals or between animals and humans. The Old Man and the Sea is an example of that. During several days of struggle, Santiago “dialogues” with God and even more so with the swordfish that he drags on his fishing line, asking it for forgiveness and telling it that he loves it, but that what has happened in their encounter in the Gulf Stream is the law of life and that both of them — fish and fisherman — know the rules of the game. Another, lesser-known example is the story of a hunt in Africa, contained in his posthumously released novel, The Garden of Eden. In this story, Hemingway describes death — actually, an execution, or coup de grace — of a long-hunted elephant, that is finally killed by a hunting party in the following manner:

“Now all the dignity and majesty and all the beauty were gone from the elephant and he was a huge wrinkled pile.”

Hemingway could not help but see the elephant as an ethical, aesthetic being, a creature with a soul and thus possessing dignity, beauty and majesty, and it is erased, vaporized and transformed into nothing. However, before arriving at its tragic end, the elephant in the story has defended itself courageously. It has caused devastation of all kinds in its flight and has harshly punished its hunters, who have paid a heavy price (physical and moral) for their prey.

One might think that Hemingway was a hypocrite of the worst sort, because it is well known that the great writer loved fishing and hunting. However, with a more careful, thorough reading of his work and life, we can appreciate that from his perspective, that paradox did not exist. According to Hemingway, we live in a world that is made out of violence. Life is violence, violence that underlies the struggle for survival and in the law of the jungle (or of natural selection, according to Darwin). Human beings cannot escape these forces, and unfortunately, they increase them and even practice them without any biological justification. In the face of this panorama, Hemingway found sustenance solely in a code of ethics and aesthetic derived from his personal experience for recovering some sense of meaning for life: to always struggle to the end, not to betray one’s convictions, to dominate fear and to do so elegantly and stoically, to completely worship dignity and to leave that legacy to those who come after you. It was no coincidence that he paid tribute to the anonymous chipojo lizard on his farm.