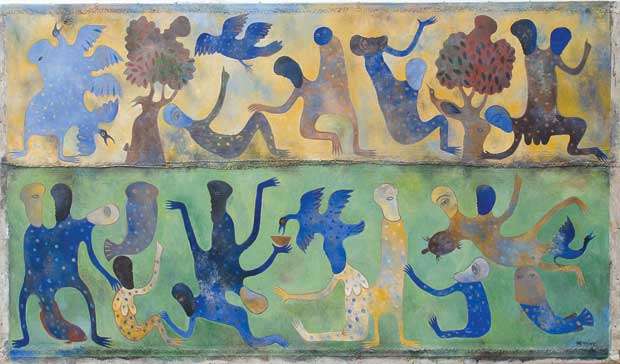

His work “almost always” has hidden symbols but he prefers for “people to discover them,” because one of Manuel Mendive’s goals is to communicate with the public and for people to understand what he is saying, in an exchange that becomes a private conversation: “When the simplest spectator—someone who perhaps does not know who Pablo Picasso is—is moved, I get excited. That really is magic,” he says.

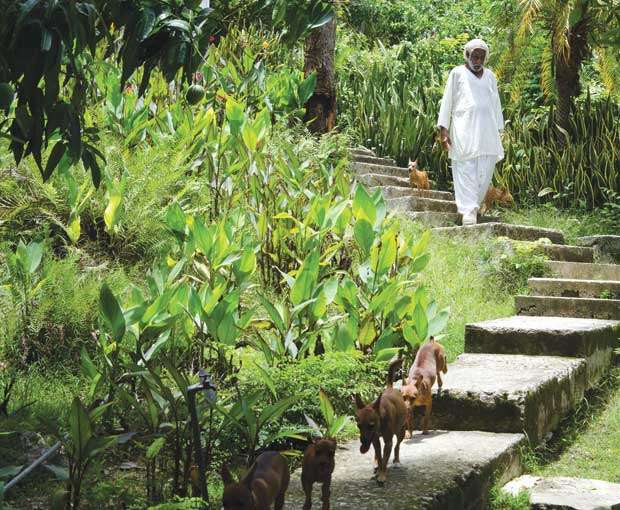

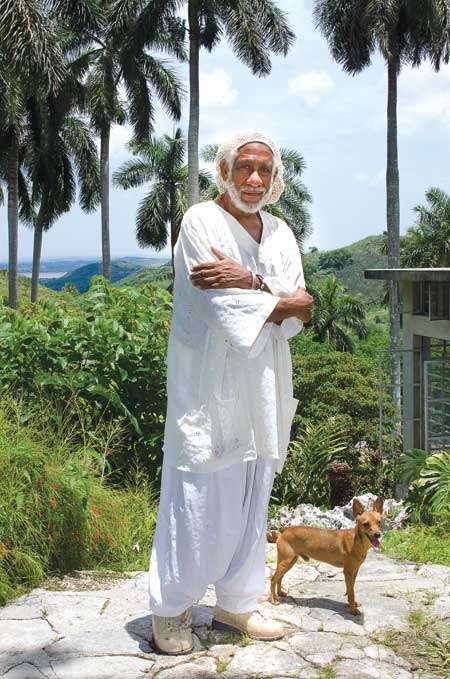

Mendive was born in the densely populated Havana neighborhood of Luyanó on Friday, Dec. 15, 1944, but he feels best when he is in touch with the land, with animals and plants, and that is why he now lives on his farm, Manto Blanco, on Las Peregrinas hill in Tapaste, on the outskirts of Havana. There, “even though I am isolated, I am never alone; I was born in Luyanó, but I was reborn here.”

This painter, draftsman, installation artist, engraver, muralist, set designer, graphic designer and performance artist is one of the most prestigious Cuban artists at home and abroad, and is viewed by many as being at the same level as virtuosos such as Servando Cabrera Moreno, Antonia Eiriz, Raúl Martínez and Umberto Peña, something that motivates him to “do work that is good, worthy and courageous, for Cuba and for the world. That responsibility is not a burden; on the contrary, it is a joy.”

As a son of [Yoruba goddess] Obbatalá, Manuel Mendive—whose speech is deliberate and reflective—told OnCuba in an exclusive interview that his cosmogony can be considered magical/religious and based several pillars: the Yoruba religion, life, faith, mysticism, kindness, gentleness, and also anguish, and above all never lying. “I always tell the truth, I say what I feel.”

He is a 1963 graduate of the San Alejandro National Academy of Fine Arts, with a specialty in painting and sculpture, and is deeply grateful for his time at that institution, which gave him “the principles, the foundations, the knowledge; that is, all of the tools that an artist needs.” And he remembers several of his professors with special affection, such as Fausto Ramos, Silvia Fernández, Florencio Gelabert and Felipe Lorenz.

Mendive was just 11 when he won an award in an international children’s painting contest sponsored by UNESCO and the Morinaga Society for Praise of Mothers, based in Tokyo, Japan. His prize-winning painting was titled “Mamá,” and it was a “beautiful, encouraging moment, my first incentive, especially because of the repercussion it had. I remember there was a ceremony at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (national fine arts museum), and the Japanese ambassador attended.” Subsequently, he participated in several national painting, sculpture and drawing salons, and in 1968 he won the Adam Montparnasse collective award for “Young Painters,” as part of the prestigious Salon de Paris, an event that he describes as “wonderful,” even though “it was ignored in Cuba, but no matter; I was well-known and chosen. At that time I was in my 20s, and it was another significant step in my career. Applause helps, and so do good eyes. Encouragement is important, and unfortunately, not everybody is encouraging or knows how to be.”

Mendive is an artist who is known for working with a diversity of media, from the trunk of a palm tree to the pores of a canvas or a piece of poster paper; he confesses that it’s because “the work asks for it, and wants it that way.” The human body has been one of his favorite media; so-called body art—that ancient tradition that combines dance and body makeup—is something Mendive exploits extensively. While he is aware of the fact that it is an ephemeral art—“Isn’t that how life is too?” he asks—he emphasizes that he was always interested in painting skin because “I wanted to do what they did in ancient cultures, but in a different way. I wanted my work and my imagination to emerge from the body of a human being to create another being. Skin has a very beautiful texture and is synonymous with life. Every body has a different anatomy, leading you to insinuate images, and every person has his or her own energy. The bodies that I use don’t have to be slim—there are those that are thicker, younger, or older; they are all full of beauty.”

Among the continents he has visited, Africa is a special place; he has been welcomed by Benin, Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia, Angola, Mozambique and Egypt, and many others. That is where our roots are, and he says that despite any differences, the essence is the same. “The feeling is the same, but what interests me the most is the relationship that exists: the body, skin, color, vegetation, animals, concepts, poetry…it is all mixed together. I never feel strange or like a stranger in any country, because I think that everybody understands my art. When I was in Russia, that’s how it was, just like when I was in Africa and Japan, or Egypt, or France, or Italy, or the United States…. I communicate through my art, and that is a moving thing, but at the same time, I feel tied to my homeland, which for me is light; the rooster’s crow, the animals, the palm trees, the vegetation, the mockingbird’s trill and the good people; I can’t live without it,” he says.