In late November 1999, Claudia Valenzuela, 40, was going through her third pregnancy. At the height of the fifth month of pregnancy, she still did not know what to name her baby on the way.

In those days, when a new century was about to arrive, the news abruptly broke out that two fishermen had rescued a boy a few miles off the coast of Fort Lauderdale, in Miami. The six-year-old boy had appeared clinging to the chamber of a tire, alive but semi-conscious and dehydrated.

“A pod of dolphins caught our attention and we followed them. They guided us directly to where a child was floating in a tire,” one of the rescuers told the press at the time.

It was Elián González Brotons, the Cuban boy who, with his mother Elizabeth and another group of people, tried to cross the Straits of Florida from Cuba aboard a battered boat. Halfway through the voyage the boat’s precarious engine failed, the boat capsized and sank. Most of the people on board died (among them Elián’s mother). The boy and two other people survived after several days adrift.

For months and in almost the whole world, details and events surrounding the litigation for the custody of the child, for the reunion with his father, Juan Miguel González, and the return to his homeland were news on the main television channels, in various newspapers, on radio stations and even on the then incipient internet web pages.

From her house, in a humble and working-class neighborhood of the General Rodríguez party, in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, Claudia followed the story in shock, with her belly almost about to explode. Through the local media, she kept abreast of the details of “The little Cuban rafter,” as the media themselves framed the story.

For Claudia, the name Elián was becoming familiar and tender. It sounded original, melodic and unusual to her.

In particular, about that name, Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez wrote in “Náufrago en tierra firme,” an article published in March 2000 where the Nobel Prize for Literature shared his immediate feelings about the Cuban boy:

“The name has attracted attention outside of Cuba. It has been written without shame that Elián was his biblical patriarch, and a newspaper has celebrated it as a discovery by Rubén Darío. For Cubans, on the other hand, Elián is a name like any of the many they invent behind the back of the saints: Usnavi, Yusnier, Cheislisver, Anysleidis, Alquimia, Deylier, Anel. However, what Elizabeth and Juan Miguel did was create an equitable name for the newborn with the first three letters of her name, Elizabeth, and the last two letters of Juan’s name.”

In April 2000, after five months of legal and diplomatic wrestling; campaigns for “Eliancito” to stay in the United States, on the one hand, and, on the other, massive marches on the island and demonstrations of solidarity around the world (including in the United States itself) in favor of his return to his country, the little boy was reunited with his father. Two months later, in June, when all judicial instances ruled in favor of Juan Miguel, father and son returned to Cuba to put an end to the nightmare.

On April 5, 2000, in a hospital in the city of General Rodríguez, west of the Argentine capital, Claudia gave birth to her third child. She named him Elián Ángel.

In the midst of a hostile context, in a neighborhood where precariousness is common currency and daily life is uphill almost all the time, Claudia managed to get ahead, practically alone raising her three children (a girl and two boys).

I spoke with this “mother courage” for a few minutes behind the scenes of a large stage set up in Tecnopolis, the premises of the National Ministry of Culture, which houses the largest mega exhibition of science, technology, industry and art in Latin America.

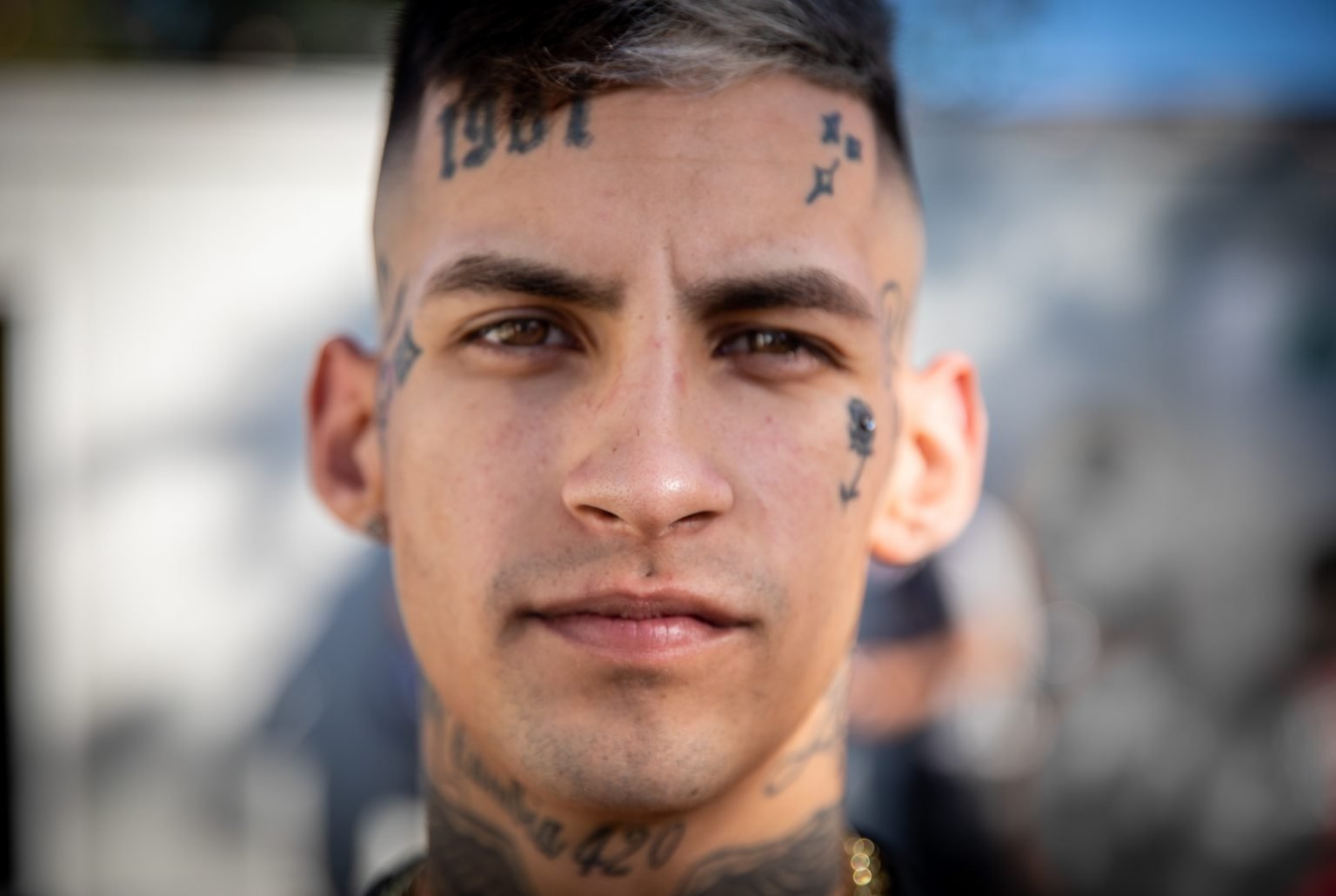

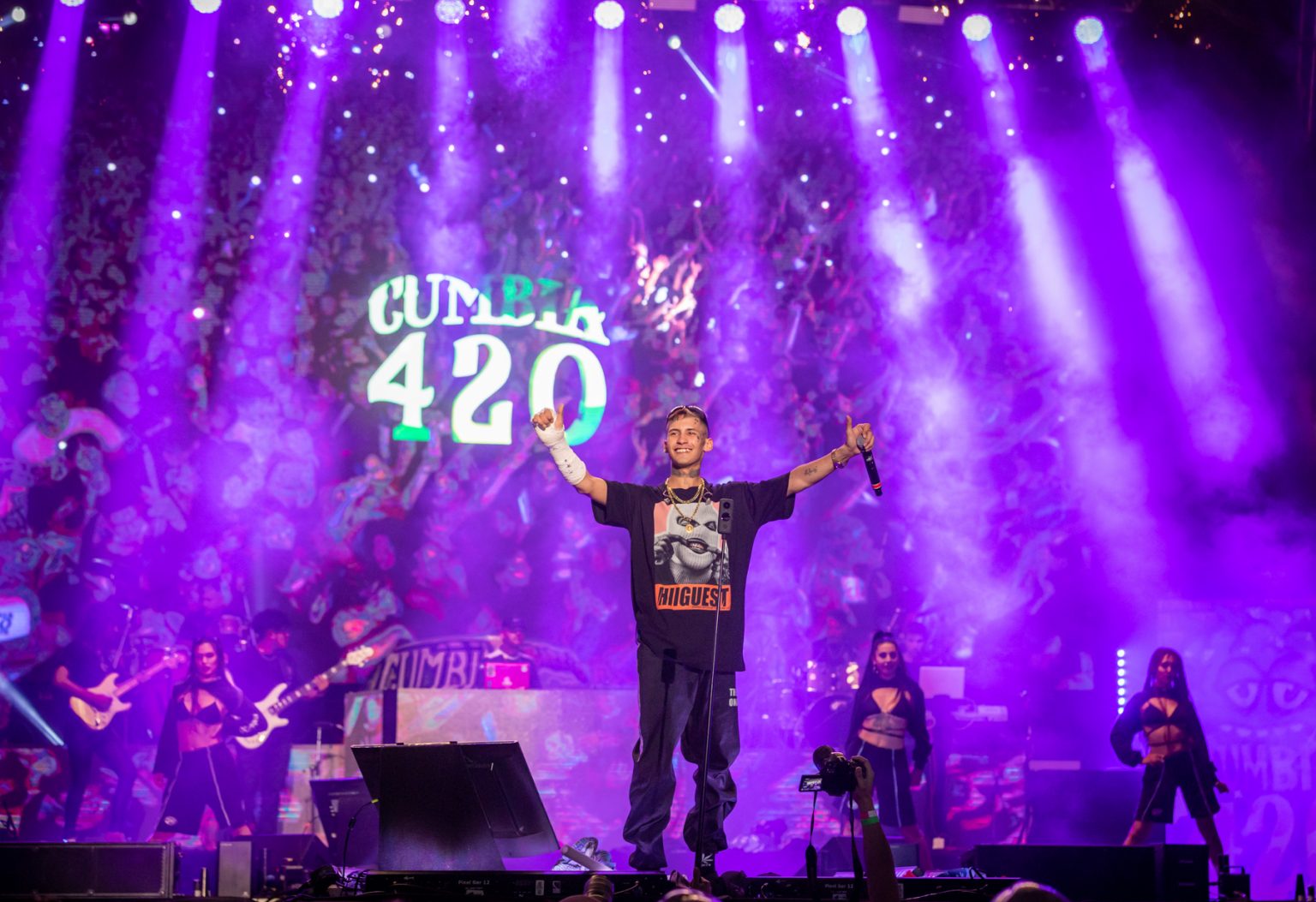

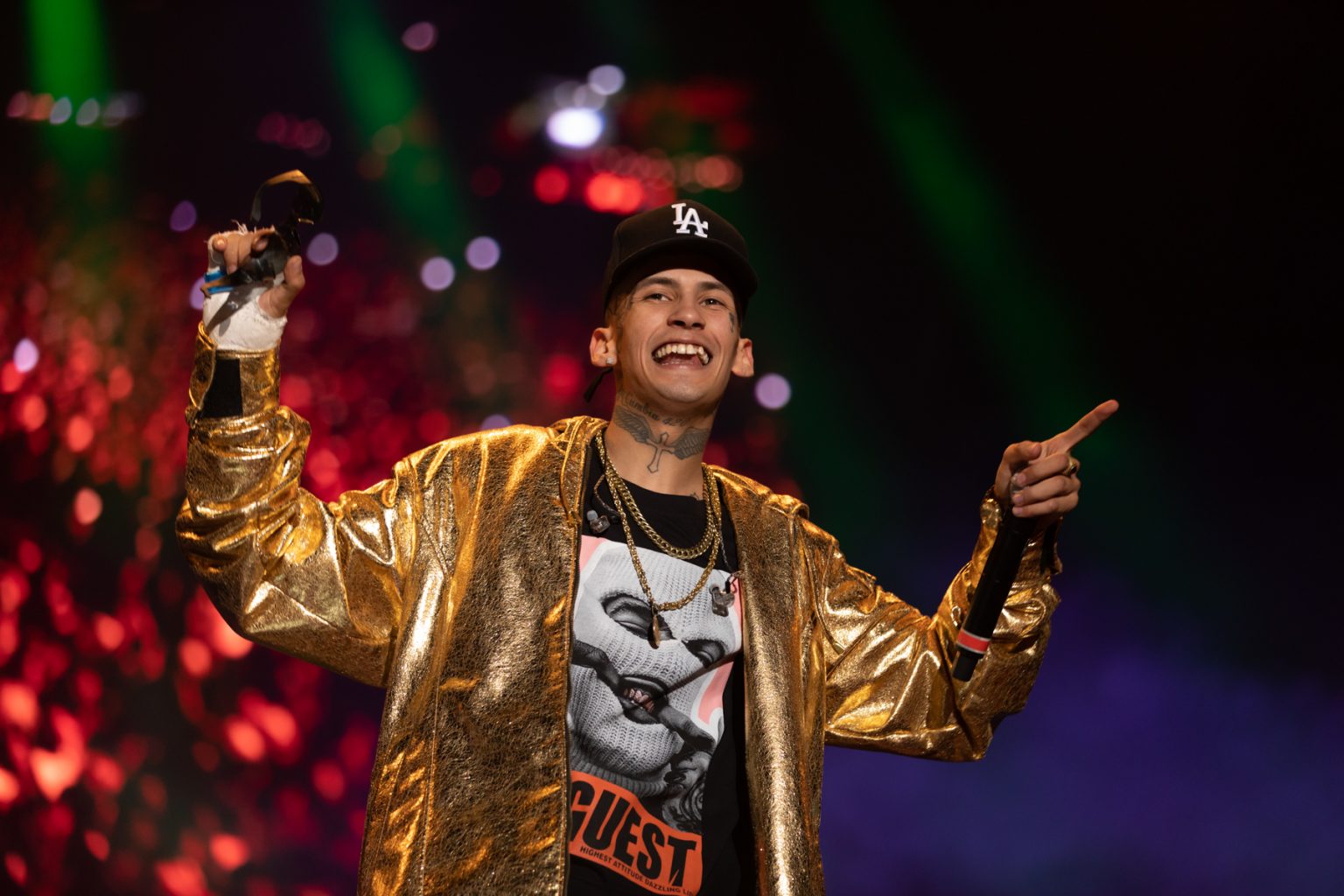

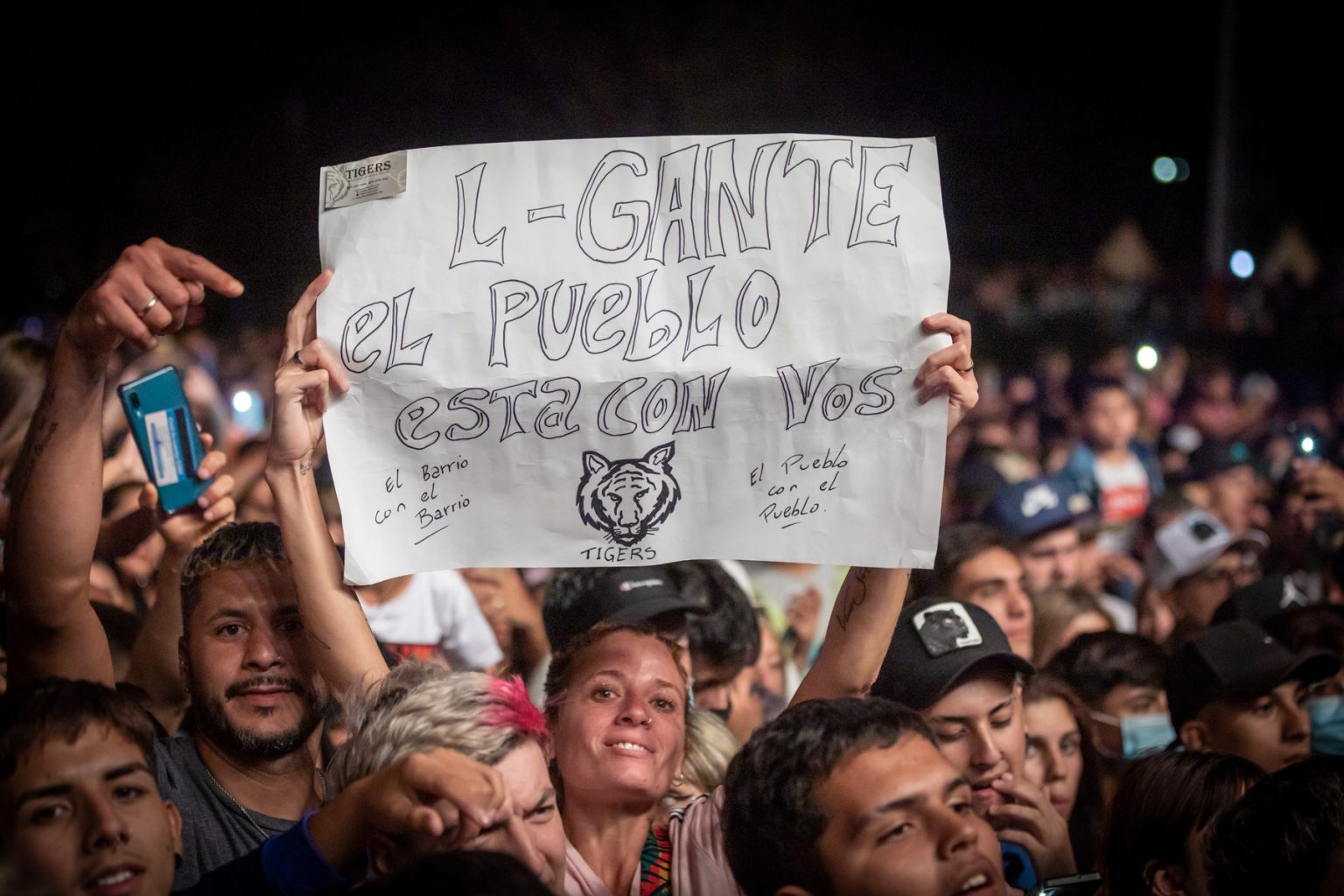

There, in that open-air theater, Elián Ángel Valenzuela, Claudia’s son, the humble “kid” from General Rodríguez who is now 21 years old, who is now, artistically, known by millions of people as L-Gante, would give a free concert for more than 45,000 fans who gathered early to listen to him and dance to the rhythm of Cumbia 420. L-Gante is a benchmark of the genre, a kind of fusion between trap and reggaeton, based on cumbia.

Claudia was surprised when I told her that I was Cuban, that I knew that boy (today a young man of 26 years) from whom she took the name for her son. That was when she excitedly told me her story and even expressed her wish that one day, her Elián could meet her Cuban namesake. “That meeting would be a dream because that little Cuban enlightened me with his name,” she told me tenderly.

Her son, who was already preparing to go out on stage, went further in her wishes: “I would love to meet who inspired my name and even be able to go to Cuba to sing. It would be great,” he let out excitedly as he posed with his mother for the picture.

L-Gante Keloke

Elián Ángel Valenzuela, the L-Gante Keloke, has become in a short time one of the most popular and followed singers in Argentina. He started writing his songs at the age of 15 while he was working in a plastic factory, exposed to high temperatures from 6 in the morning to 3 in the afternoon. One day he resigned to bet everything on music.

Claudia supported her son’s decision. She was always like this with all her children. She encouraged him to continue along the paths of music and, although the family economy was not at all comfortable, he paid for his first recordings.

The name L-Gante also came from her. The boy would wake up and with the same clothes he had slept in he would jump to the computer to put the ideas that were going through his head into the soundtracks. He could be at that all day, in front of the small screen, wearing his pajamas. The mother saw him and would ironically tell him: “How elegant!” That’s how Elián created his artistic pseudonym L-Gante, to which he later added “Keloke,” for the greeting he used to exchange with his friends in the neighborhood.

DR Bilardo, the star producer who bet on the talent of the young man and one of the godfathers of Cumbia 420, explains that the novel genre “is the new cumbia and is characterized by the backward rhythm. It is the fusion between different street styles in a single genre where each one puts its essence. It is a musical style with the soul of cumbia and reggaeton.”

L-Gante’s lyrics are straight forward. He speaks with the legitimate and humble language of his neighborhood. They tell about their daily lives, problems and dreams in simple, crude and real stories.

For the song “Pinta,” L-Gante joined Bizarrap and Pablo Lescano and was included in the successful Netflix production, El Marginal, says:

His favorite phrases are “L-Gante, perro, keloke?” “Cumbia 420, pa’ lo ‘negro,” “Aguante el barrio con el barrio.” In these statements, the artist embraces those who, like him, have been and are constantly neglected and excluded by the system, those who are stigmatized because of their clothing and social status.

“L-Gante RKT” was the smash hit that catapulted Elián.

He recorded it in his bedroom, with a cheap microphone and a school notebook from the Connect Equality Program, an initiative created in 2010 by the State to recover and enhance public schools in order to reduce digital, educational and social gaps.

The song was released in 2020, through social networks and its YouTube channel. In less than a month, the hit reached more than a million views. Today “L-Gante RKT” has more than 275 million views on YouTube.

According to statistics published in October 2021 by Spotify, the famous music streaming platform, “Cumbia 420,” by L-Gante, “became one of the predominant styles among young listeners, to the point that 50% of those under the age of 25 include it on their lists.”

Elián’s popularity grew not only digitally and among young people, but among the youngest, he is also very popular; especially after he ingeniously recorded the alphabet to the rhythm of Cumbia 420.

“L-Gante’s mass following is the product of a phenomenal crossover between this recognition effect and the world of hyperconnectivity and social networks, amplified to infinity in times of pandemic and confinement,” reflects Pablo Semán, professor at the University of San Martín, in “L-Gante: la vida no entra en meme,” an essay published in Anfibia magazine.

In that text, Semán also points to something deeper and sociological to take into account to start understanding this mass phenomenon.

“L-Gante and many others who live a life like his have a specific relationship with the powers and a vision of their own that these offside captures ignore and oppress. L-Gante conceives himself explicitly as part of an era in which new technologies can be used by subjects like him to enhance their ability to generate a musical phenomenon, win audiences, have an income, establish an aesthetic pattern coming from down. And that is why the young musician says that it is good that there are computers and that they have to be used and he understands that they are a weapon so that young people like him can reverse differences by finding in them the ability to carry out aesthetic and labor projects, expressive and monetizable.”

A couple of songs before the end of the show in Tecnopolis, L-Gante brought his mother Claudia on stage, his girlfriend Tamara and their little daughter Jamaica, who was only a few months old. Behind the scene were his friends, those from the neighborhood, who effusively applauded him to the rhythm of the Cumbia 420 movement, as did the tens of thousands of people who came to see him.

Elián is aware that he has become a benchmark for a large part of youth and children. Neither fame, popularity nor money have clouded him. That is why, from his place, he takes the opportunity to send messages of encouragement and hope.

“You have to move forward. I fulfilled my dream, but how much more lies ahead of me, how many more things to know, learn and be. So that’s good, always forward. With humility. The neighborhood with the neighborhood,” he said excitedly before the crowd.

Also before the thousands of attendees, he reaffirmed his commitment to finish his secondary studies, which he interrupted a few years ago to dedicate himself to work and thus sustain his musical career.

“I’m already fulfilling my dream but… how much lies ahead? Many more things I can do and be! That’s why I want to finish school,” he said towards the end of the concert. He himself has stated that he would like to study medicine or law.

Everyone wants a picture with L-Gante. To hug him, they want him to send greetings to a family member or friend. The young man stops at every step. He doesn’t care if the tide of people carries him away.

Claudia’s green eyes send flashes of light. She observes tenderly the signs of affection that her Elián receives from the public and smiles. Dreams definitely do come true.

Kaloian Santos Cabrera

With a Soviet Zenit camera, some money and a bag holding more illusions than clothes or food, I started traveling with my backpack through Cuba when I was 18 years old. Photography and journalism then appeared as a need and would become for always a form of militancy.