A good friend sent me a few weeks ago a speech that has circulated mainly on social networks and is attributed to the President of Uganda, on the meaning of COVID-19. It is perhaps, as she told me, the most instructive of all the ones I’ve read. In one of its parts he states: “The world is at war.… A war without guns and bullets, a war without human soldiers. A war without borders.” Without a doubt, he is right.

What I learned by reading and watching many war films, especially World War II and specifically the Great Patriotic War, the one that the Soviets won against German fascism and that today many interpretations intend to forget or relegate to the background is that the vanguard, being decisive, can only be truly successful if it has a powerful rearguard. Those great tank battles, where the Red Army literally crushed German armored divisions, were only possible because the rearguard produced the steel, the bronze, the engines, and finally the tanks. Without a powerful rearguard, it would have been very difficult for the Red Army to take Berlin.

Cuba is also waging this new war. It does so every day and every morning we receive the report.

But that isn’t the only war our country is waging. There are others, as old as us Cubans; others, a little less old, but also old and others more recent. Some are fought against external factors, others, on the contrary, have to do with internal factors; some are evident and tangible, others are not so obvious and it is often difficult to make them visible.

In this war against the pandemic, from my perspective, the vanguard is our healthcare system. All of it: from medical schools and health personnel to the simplest and most remote of the family doctor’s offices. Our pharmaceutical industry, especially the system associated with biotechnology and its research, development and innovation system, with all its research centers, constitutes one of the most powerful weapons of the vanguard, that of its doctors and scientists. I think its capacity for response, it agility and its results leave no room for doubt.

There is, however, a great asymmetry between the behavior of the vanguard and that of the rear. By rearguard I understand that other system that should provide the necessary means for Cuba to face the pandemic in better conditions. For this, the production and supply of food is decisive.

The rearguard is made up of those sectors responsible for producing/supplying a group of goods and services, some of them essential and others perhaps relatively dispensable, but which should help to wage this war. I am talking about the sector that produces food —agriculture and food processing industry—, and of those others that guarantee services that have become very necessary: commerce, in its different forms (physical and electronic) and banking, for example.

From the furrow to the table: removing obstacles and obstacle-makers in food production in Cuba

Perhaps one of the lessons that this war against COVID-19 has left us is to confirm how insufficient a good part of those services were already and how wrong our perception was about it.

For example, today we discover how insufficient the existing network of stores is in our country, including the capital of the Republic and, especially, some of its peripheral neighborhoods. We also discovered how badly we use the most widespread and accessible trade network, our grocery stores (of which I believe there are around 12,000 in all of Cuba); how necessary it is to increase the number of bank branches, to reduce lines and paperwork time; how much we still have ahead of us to reach adequate service standards in the now so popular electronic commerce (which a year ago we thought was going well); how much more progress can be made in the computerization of society and how long it has taken us to do it (undoubtedly, in recent years there has been progress in this, although not enough).

But the hard core of the rear is food production. This has not achieved the necessary response either in time or quantity or quality. It has forced the authorities to wear themselves out in a daily biblical exercise (that of the miracle of the loaves and fishes) and, at the same time, it has subjected our population to unprecedented rigors and shortages that were almost impossible to imagine.

Here the shortcomings have become more than evident. They are, in some way, one of the main causes of dissatisfaction and discomfort of the population and probably one of the issues (perhaps the second) on which the country’s leadership spends more time.

Little remains to be said of primary food production; it has been written from almost every angle. Anicia García, using a series of data up to 2017, long before COVID-19 and still without suffering the effects of the Trump government, sums it up with this statement: “The differences in productivity between the Cuban agricultural sector and the rest of the country’s economic activities allow us to affirm that the sector, far from contributing to the economic development of Cuba, has become one of its main difficulties.”

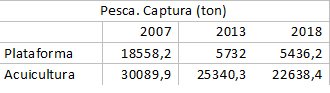

The evolution of fishing results shows the productive deterioration.

*Caption:

Fishing. Capture (ton)

Platform

Aquiculture

The argument of overexploitation of our seas as the fundamental reason for the decrease in catches is always striking, something that contrasts with the fact that, for many years, the catch of platform fish has decreased substantially. In 2018 it was less than a third than in 2007. A curious fact is that, in 1960, when aquaculture still did not exist, the catch of fish in Cuba reached the figure of 31,200 tons and almost 100% was caught in our platform. During the years 1960-1965, the catch was never less than 30,000 tons (ONEI. AEC).

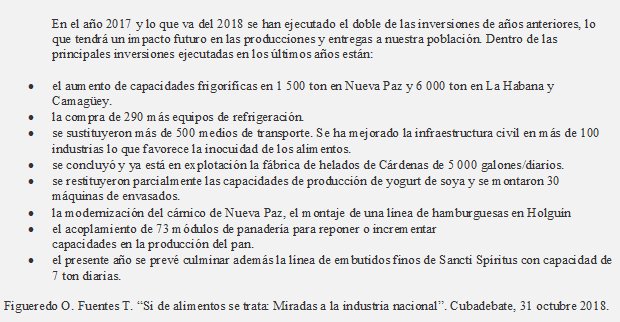

The food processing industry also leaves much to be desired. In a Mesa Redonda TV program of October 2018, reproduced in Cubadebate, the officials of that industry explained how much had been done and was being done. They maintained that from 2017 to October 31, 2018 “double the investments of previous years have been executed, which will have a future impact on productions and deliveries to our population.” They referred to the main investments made in recent years.

*Caption:

In 2017 and 2018 to date, double the previous years’ investments have been made, which will have a future impact on production and supply for our population. The main investments carried out in recent years include:

- Increase in refrigeration capacities of 1,500 tons in Nueva Paz and 6,000 tons in Havana and Camaguey.

- Purchase of 290 more refrigeration equipment.

- Replacement of more than 500 means of transportation. The civil infrastructure has been improved in more than 100 industries, favoring the innocuousness of food.

- The ice cream factory of 5,000 daily gallons in Cárdenas was concluded and is already operational.

- Soy yogurt production capacities are partially restituted and 13 packaging machines were installed.

- The modernization of the Nueva Paz meat-processing plant, the assembly of a hamburger-producing line in Holguín.

- The connection in series of 73 bakery modules to replace or increase bread production capacities.

- Plans for this year also include finishing the fine sausage line of Sancti Spíritus with capacity for 7 tons a day.

A weak primary production of the agricultural sector and the cut in imports of external supplies explain a good part of its meager results, although there are undoubtedly other causes.

Two years ago, it was also explained that the development program was aimed at “gradually restoring food production…technological modernization, maintenance, the market, the nutritional requirements of the population, the diversity of formats and assortments, the preparation of human capital including cadres; all from a scientific basis.”

For those years, the sector had “12 joint ventures in operation, 7 foreign association contracts, 11 joint ventures are also being negotiated, four of them linked to agriculture for the production of dairy and meat products and there are more than 40 projects in the portfolio of opportunities.”

Unfortunately, it is difficult to follow up on what was reported in 2018, based on this September’s presentation. However, it was known that there are 16 businesses with direct foreign investment in operation and four new joint ventures have been approved in 2020, for the production of beers, soybean oil and flour, juice and ramen, and an economic administration contract for the marketing of rum. It is stated that “by 2030 the Food Industry Development Program conceives of 58% participation of foreign investment, and to date 45% has been executed.”

It doesn’t seem like little; however, we are still far from what is needed.

If the effort of the State, added to foreign investment, is insufficient, wouldn’t it be good to also think about adding the effort of the national private and cooperative sector, as a “complement”?

The war against COVID-19 leaves us with a long list of possible improvements, of potential jobs to create, of spaces that can be filled both by the effort of the State and by the opportunities that this may mean for the private and cooperative sector, that can be exploited by territories, society and people individually, with profits for all. Crises are always an opportunity for improvement and innovation.

It’s true that the rearguard matters, but it is also true that it is not everything. Armies with a tremendous rearguard have lost wars against others with barely an elementary infrastructure. Vietnam, Afghanistan and we ourselves are a good example.

However, for this war we are waging today, we urgently need to upgrade the rearguard. This should later become the forefront of the vanguard of another major war: that of all the people for their well-being.