The first modern atlas, of which there are only three copies in the world, belongs to the collections of the National Library of Cuba (BNC). But it has not always remained there. In the 1990s an expert in valuable works stole it from the institution and sold it to the Boston Athenaeum. Now, two decades later, the copy has been returned to the island.

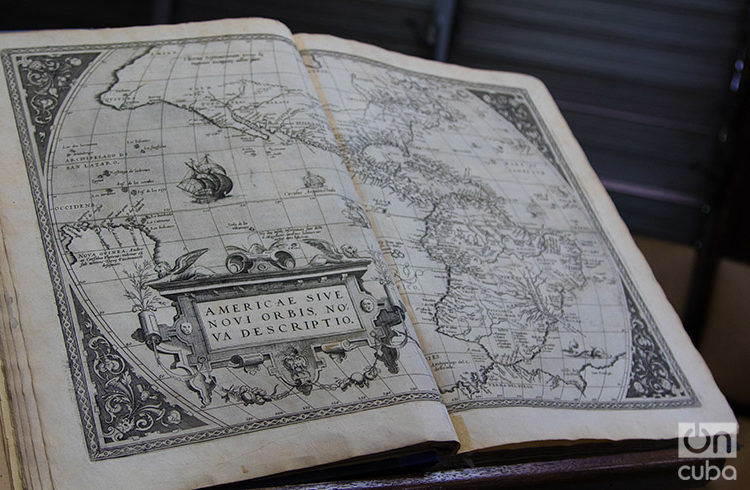

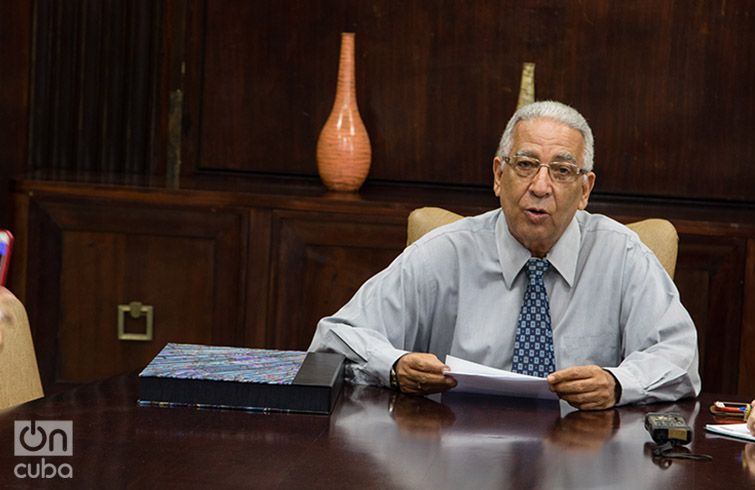

The atlas published on May 20, 1570 in Belgium collects for the first time maps of America, the Antilles and Cuba. For Dr. Eduardo Torres Cuevas, outstanding historian and director of the National Library, one of the document’s greatest values is the location of Cuba in the Antillean, American and world geography.

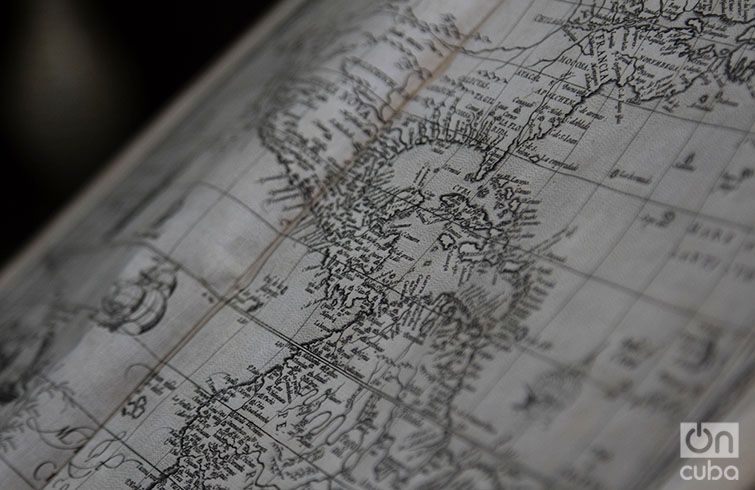

It is a collection of 53 maps with their corresponding texts made and engraved in copper plates that show how the world looked at that time. “America appears here very disfigured, which is logical if we take into account that it is made following the description of navigators. But at least thanks to Ortelius the island of Cuba is included in an atlas, although drawn much smaller than Santo Domingo, typical of 1570,” says Torres Cuevas.

Its author, the erudite and geographer Abraham Ortelius, made other versions after 1570 where he introduces other maps. The atlas grew in each one of its 31 editions. Originally in Latin – like this copy – it was published in seven different languages: Dutch in 1571, German in 1572, French in 1572, Spanish in 1588, English in 1606 and Italian in 1608.

The Ortelius Atlas was stolen from the National Library at some time between 1990 and 1993, a period in which many works of art were lost in Cuba. Everything indicates that Boston antique dealer David L. O’Neill acquired it in an auction and in late 1993 sold it for a high price to the Boston Athenaeum, one of the oldest and most valuable private libraries of the United States.

When did the Athenaeum find out that the atlas had been stolen and how did it identify that it belonged to the José Martí National Library? These were some of the questions asked by Dr. Eduardo Torres Cuevas during the initial exchange with the U.S. institution.

“In the summer of 1999 the Atlas was sent to the Documents Conservation Center in northeast Boston and on December 14 of that year Mrs. Deborah Wender, head of the conservation center, reported that after a rigorous inspection they had detected that two of stamps of the owners of the Atlas had been mutilated. One of them could be deciphered. It identified that the work belonged to Havana’s José Martí National Library. And, on the other hand, no other sign existed that the work had been liberated from its collections. These are reasons given by the Documentation Center to not work with the book. Because of a question of ethics the institution does not process stolen books,” says Torres Cuevas.

For museums and libraries in the United States it is a routine process to review its purchasing decisions, for financial or legal reasons as well as in terms of ethics and academia: “Where did the money come from? Was the law followed? Should it form part of our collection? Is it at the same level in terms of quality as the rest of the collection? The review necessarily takes a certain time after the acquisition,” Jorge Domínguez, director of the Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies, explained to OnCuba.

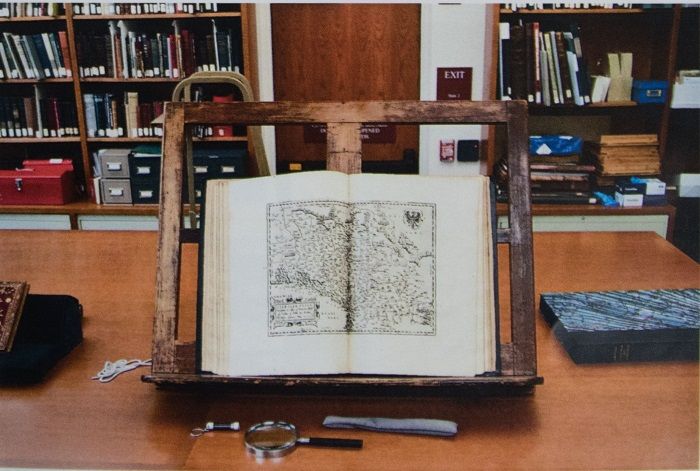

Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum [Theater of the World] returned to the Boston Athenaeum on November 16, 1999, protected by a box with leather binding that the Library ordered from the Conservation Center to preserve the volume. The Athenaeum’s investigative work would last for a few more years. In 2001 the library would confirm that the book belonged to Cuba.

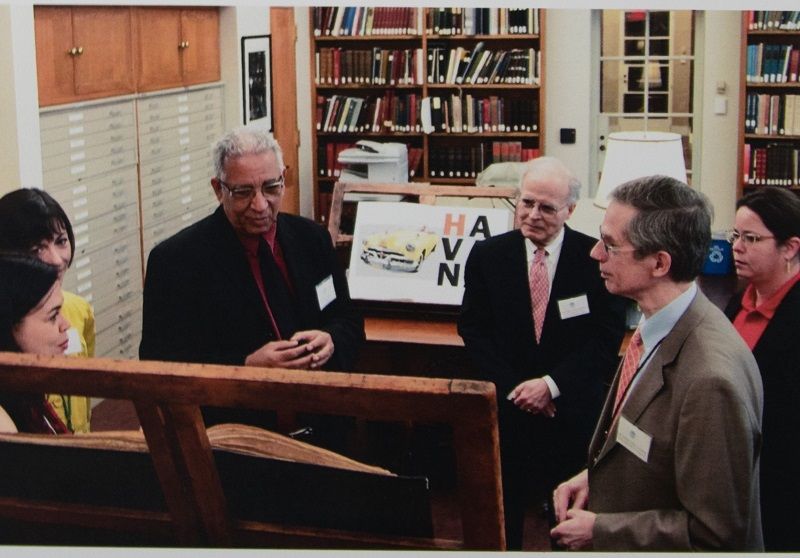

“There were technical details. The first was that the thief, or the person who bought it from the thief, tore out the cover and inserted the atlas between ugly cardboard covers. That in itself was not decisive but it did facilitate a careful review. Then the key was to detect, with a device that magnifies what is printed and stamped, the erased stamps – fortunately not all of them – that identified the atlas, with no doubt, as the property of the José Martí BNC,” says Domínguez, also a professor of studies on Mexico in the Antonio Madero Chair of Harvard University, who served as the link between the Bostonian center and the Cuban institution and facilitated that the return be directly to the director of the BNC during a recent visit to Harvard.

On May 23, 2016, the board of governors of the Athenaeum approved the return of the Ortelius Atlas to Cuba and on April 6 of this year the board of the Boston Athenaeum concretized that it be handed over to Dr. Eduardo Torres Cuevas.

But if the book had been identified since 2001 as property of the Cuban library, why did the handing over of the document take so long? Professor Jorge Domínguez explains why to us:

“I believe that part of the delay was due to the need to discuss it with lawyers, the board of governors of the Athenaeum and possible donors. When the theft was detected a difficult process of inquiry went by, because it happened, which are legal responsibilities of the institution, and it is then that it is communicated to the donors of the Athenaeum who depend on the professionalism of the institution.

“Beyond the framework of the Library there is also the consideration of the handing over according to U.S. laws and the pertinent UNESCO conventions. Even so, time went by, and I suppose that the matter of the return was presented as a consequence of the U.S. change of policy announced in December 2014.”

The Boston Athenaeum, founded in 1807, has been constituted mainly based on the donation of books, works of art and money. Its funds are used among other things to acquire works that combine its two principal commitments: books and art. “The atlas returned to Cuba is a perfect example of that combination, it is truly a jewel of incalculable value, therefore the act of returning the stolen atlas is even more impressive since in the Athenaeum they lost the money that had been paid for the Atlas,” says Domínguez.

Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is a rare work in the world. Only three copies of the 1570 edition are registered: one in a Madrid library, another in a private collection and the third which is in Cuba.

“The quality of its pages is very superior to the contemporary,” Domínguez explains, “and that’s why it is in such excellent conditions almost half a millennium after its publication. A geographical detail is that the atlas demonstrates better knowledge of the Caribbean than of other parts of the hemisphere, since the cartographic details of the Antilles are the most precise of that map.”

The theft of the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum coincides with other thefts in the BNC during the Special Period: “I remember that on visits to Havana, touring the streets of the historic core of the city, I saw books on sale that were evidently stolen from the Library,” says Domínguez.

The José Martí National Library currently has among its collection around six million books, to which could be added a large number of missing works that have been lost throughout time, especially between 1989 and 1995, a period in which the institution identifies its largest amount of losses.

“We must recognize that during those years our works were not sufficiently protected, especially because there was great trust in the honesty of the workers of these institutions and that facilitated that part of our collection was plundered. We are aware that due to its large size, the theft of the atlas was not a simple process for the thief, who took it out of the library and later took it to the United States,” the director of the BNC affirms.

“Nowadays it is very difficult for these things to happen again in the same magnitude. In the last 10 years the work to ensure the care of these works has gotten tougher, although there’s always an area of vulnerability where there isn’t all the necessary care. We have a vigilance program in each room and a system against intruders, but anyway the cameras and security measures that exist in the Library are not sufficient,” Torres Cuevas adds.

The Athenaeum’s action is the first return of a valuable work to the BNC. However, its director affirms that at present there are collectors from diverse parts of the world handing over important documents and books, as is the case of researcher Lu Pérez who is returning all the information with which he has worked in the United States.

“We are in a moment in which many things we have lost can be recovered. We have to continue recovering those works that for a long time made up the country’s heritage,” says Torres Cuevas.

For the time being, the first modern atlas of the world is again in the Rare and Valuable collection of the José Martí National Library. Its recovery represents one of the most important events in terms of the recovery and conservation of the national heritage: “This is one of the most valuable works the Library had. It’s not one more atlas,” the historian specifies, “it is the first modern one that was made and Cuba is proud to have one.”