I

In 1890, the Louisiana legislature approved the Separate Car Act for passengers on trains. A year later, in September 1891, a group of black citizens of New Orleans decided to express their disagreement through various public expressions, one of which is considered the first recorded action of civil disobedience in the history of the United States.

Shoemaker Homer Pessy (1862-1925) got on one of those cars reserved for whites on an East Louisiana Railroad Co. train. The man looked white (“seven-eighths Caucasian and one-eighth African blood”), but he declared himself black and was ordered to change cars. Given his refusal, they took him off the train, put him in jail and fined him for disobeying the law.

In court, Pessy argued that he had been denied his rights under the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States. But the decision of Judge John Howard Ferguson (1838-1915) did not agree with him, and he ruled that segregation on trains was legal. The Louisiana Supreme Court upheld his verdict.

On May 18, 1896, the United States Supreme Court ruled on the case, known as Pessy v. Ferguson. Rejecting argument of the plaintiff and his attorneys, the justices determined, by an overwhelming majority of 7 to 1, that a law that “merely implies a legal distinction” between whites and blacks was not unconstitutional.

As a result, public places separated by race were, in fact, legalized/legitimized. “Separate but equal” would since become a doctrine and a common expression in the vocabulary of Americans. Jim Crow segregation laws, typical of the former Confederate territories, had achieved a triumph with impacts that would last for decades.

But everything has an end. Around the 1950s, the first breakdowns would begin to take place at the hands of the same social subjects who had lost the case in the 19th century. On May 17, 1954, in a landmark decision in Brown v. Topeka, Kansas Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for students of different races unconstitutional, a decision that dismantled the legal framework for racial segregation in public schools and Jim Crow laws.

On December 1, 1955, a young Afro-American seamstress, Rosa Louise Parks (1913-2005), later called “the mother of the modern civil rights movement,” refused to get up from her seat to give it to a white passenger on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, triggering a wave of protests that reverberated throughout the United States. Undoubtedly, it is a gesture inspired by that train disobedience and one of those acts that had, now, the peculiarity of redirecting and changing the course of history.

It is therefore no coincidence that black actors appeared in leading roles in U.S. movies at that time, beyond Mammie from Gone with the Wind, a character that earned Hattie McDaniel the Academy’s Oscar for best supporting actress (1939), and other black characters from historical Hollywood, where they only fit in the roles of “savages,” slaves or servants. Not to mention their image in openly racist foundational films like Birth of a Nation, in fact a glorification of lynching.

Black actors and producers like Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte and others raise their hands and plant themselves before the viewer, and above all they underline the need to recognize faces and voices that had been invisible until then. In 1954, Carmen Jones was released, a film starring Dorothy Dandridge, Pearl Bailey and Harry Belafonte under the baton of the always uncomfortable Austro-Hungarian director Otto Preminger. That same year another change was documented: Dandridge’s nomination for an Oscar for female acting precisely for her role in that film. The first time an Afro-American was nominated for the award, which was ultimately obtained by Grace Kelly (A Country Girl) shortly before she became the princess of Monaco.

In November 1954 Dandridge was also the first black woman to appear on the cover of Life magazine in a famous photo by Philippe Halsam that marked an era to the delight of some and scandal of others. She was also the first Afro-American singer to perform at the Waldorf Astoria in New York. “One of the great beauties of our time.” “A sex symbol.” “The first love goddess of color.” “The bronze bombshell.” And “our Marilyn Monroe,” in the words of Lena Horne.

II

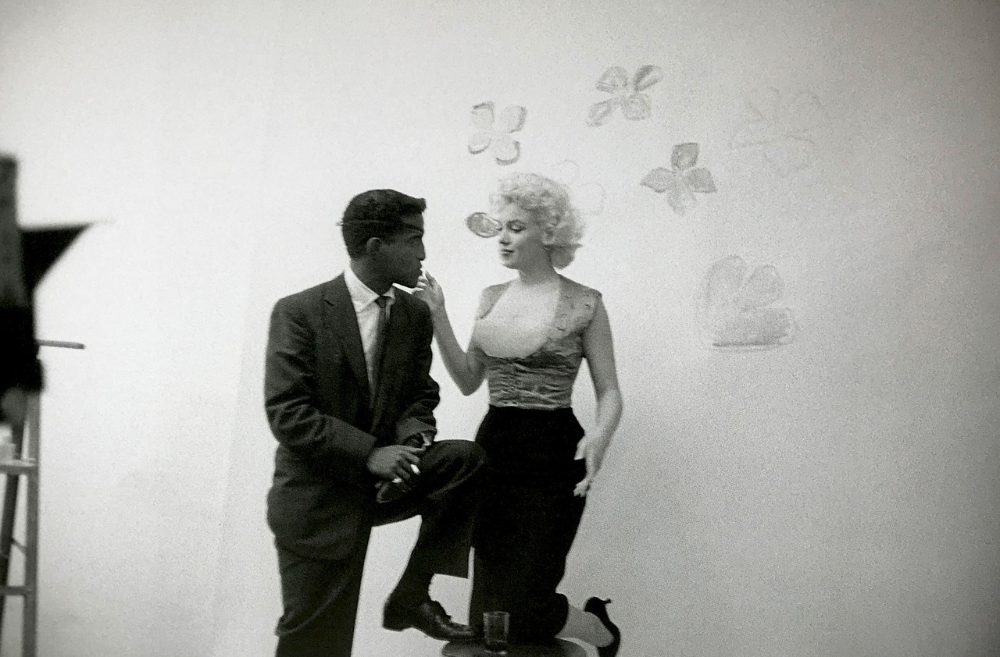

In 1955, once divorced from baseball player Joe DiMaggio, Marilyn Monroe and Marlon Brando begin to have a relationship after meeting at a party in New York City. By then Brando was already well known for his anti-segregationist attitudes, determined among other things by a life trajectory that had led him to associate with black male and female dancers and for having taken classes with Katherine Dunham (1909-2006), a dancer, choreographer and Afro-American teacher who at the end of World War II opened the Katherine Dunham School of Dance and Theatre, on Broadway and 43rd, near Times Square.

“There were only two white students; the others were black,” he wrote in his autobiography. So, he confesses, he did it for the first time with a Jamaican nurse, coming to an irrevocable conclusion: “there was no difference in making love to a colored woman and to a white one.” And he stressed: “The only difference was her color, a symphony in sepia.” This is one of his heresies. And the issue would not stop there but would also extend to Latinas and Asians.

Brando also had personal friendships with Afro-American actors, with whom he exposed himself in public, an attitude considered politically incorrect at the time, much more so in the case of a figure like his, a new Adonis for his performances in films such as A Streetcar called Desire (1951), The Wild One (1953), and On the Waterfront (1954). The same man who made white, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant women sigh, imbued with the idea that the United States belonged only to the descendants of the Mayflower, nevertheless had a serious existential problem: being part of an increasingly uncomfortable group socially stigmatized with the category of “friendly with negroes.”

That exposure to Brando’s imaginaries, together with the historical-cultural developments briefly mentioned at the beginning, undoubtedly had an impact on Marilyn Monroe’s vision of reality and horizon.

The Mocambo was the most popular club in Hollywood in the 1950s. Opened in 1941, it was frequented by the jet set and actors such as Clark Gable, Charlie Chaplin, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lana Turner, Erroll Flynn, Tyrone Power, Lucile Bal and Desi Arnaz, among many others. It featured such luminaries of the song as Frank Sinatra, Dinah Shore, Rosemary Clooney, Yma Sumac and Edith Piaf, among many others.

It was not, however, exempt from segregation and there was reluctance, even though between 1952 and 1953 Afro-Americans such as Dorothy Dandridge, Eartha Kitt and Joyce Bryant had managed to perform at that club.

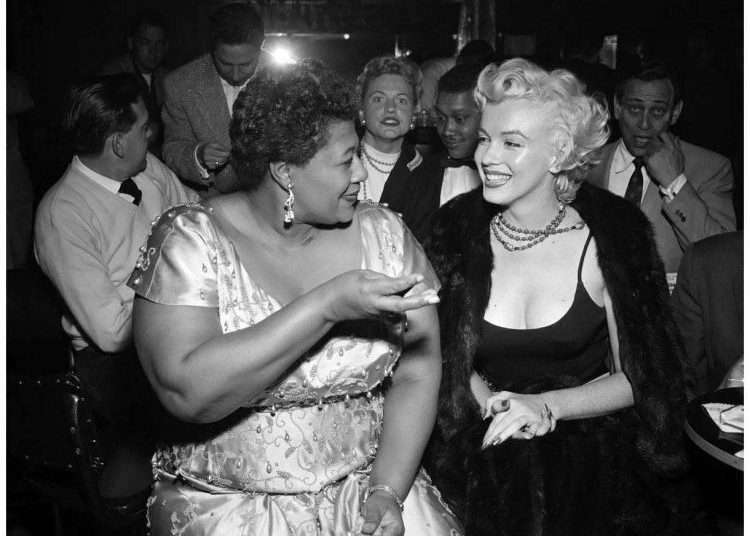

But Ella Fitzgerald, the “Queen of Jazz,” was until then limited to small stages in the city of Los Angeles, despite her exceptional energy, her crystal-clear phrasing, her ability to improvise and her unique voice. Oral history records that in 1955 Marilyn Monroe intervened to solve the problem through an agreement with the owner of the club. In August 1972, Fitzgerald told Ms. Magazine: “I owe Marilyn Monroe a real debt…she personally called the owner of the Mocambo, and told him she wanted me booked immediately, and if he would do it, she would take a front table every night. She told him – and it was true, due to Marilyn’s superstar status – that the press would go wild.”

And she continued: “The owner said yes, and Marilyn was there, front table, every night. The press went overboard. After that, I never had to play a small jazz club again.”

Marilyn Monroe broke the barrier with a phone call and her intelligence. Later, in 1958, Lady Ella would be the first Afro-American artist to receive a Grammy Award. She said of Marilyn: “She was an unusual woman, a little ahead of her time.” And she added: “And she didn’t know it.” [my emphasis]

“I like blacks because I know slavery firsthand,” the actress in The Seven Year Itch (1955) once said. Marilyn Monroe was not and could not be a civil rights activist, but she did have the sensitivity and the gray matter to break with common sense in a time of change. Marlon Brando wrote in his Memoir: “She had been beaten, but she had a strong emotional intelligence: a keen intuition for the feelings of others. The most refined kind of intelligence.”

A fact that Blonde, the film, certainly overlooks in the midst of the action of ideological presuppositions that make the central character lose her human and contradictory condition to give the viewer, instead, a linear and Manichaean vision of who is one of the most powerful myths of all time.

seria bueno mencionar que el primer actor negro

en interpretar un papel prinicipal en Hollywood y en ser nominado para premio por su actuacion!

Fue Juano Hernandez Chavez, boricua, de Santurce,Puerto Rico!