My attraction for books not registered in the inventory of edifying titles for Cuban youth turned into a disagreement with a teacher, also the Party secretary in the school.

I had just finished Compulsory Military Service, we were in 1999 and I, like Oscar Matzerath, refused to ideologically tow the line.

The debate about the material in question this time took place during my time in senior high, when that professor discovered in my hands the novel of another of those authors hated by Party members. And I say “hated” because my suffering from a chronic innocence and because I have written about prohibition and censorship other times, are also relative.

It happened when in passing the professor saw that, instead of Luis Báez’s interviews with the Cuban generals or Vitali Vorotnikov’s diary about the downfall of the Soviet Union, materials of which we had spoken at some time before his classes, I was holding a copy of La nada cotidiana, by Zoé Valdés. His pink face started getting red until it became a clot.

The book was not mine, however. It had been lent to me by my friend Rey Almarales, a frenzied reader like his brother, and we were face to face, commenting on the book when the other passed by. By some strange coincidence his attention had fallen on the cover after perhaps hearing some comment on the content and the author.

That random moment was enough to activate his fighting spirit. That how was it possible that we were reading a book by that counterrevolutionary, that this woman was not worth it and, more, could not be read in that place ―nothing less than a military senior high school, that is: the burden we had to carry for life and for which at the University of Havana a grammar teacher liked to torture me, always putting my condition of having won the opportunity to study a university career with the order 18 given by Compulsory Military Service, before any evaluative exercise where, according to her, I was destined to fail.

I was not a follower of Zoé Valdés either, but I read her novel with enthusiasm and, being stubborn, I decided to defend the work against all odds after having read it halfway. My unusual defense proved worse for the professor, and he also looked as if he were going to explode.

Somehow we both exploded, and after requesting from my schoolmate, the school’s secretary of the Young Communist League, that we had to solve it in another way, we went off down the hall. I went downstairs screaming that we would get to the General Staff or the Provincial Party headquarters to present my complaint about a literary work’s censorship. That was my intention.

We had not reached the door, and by the side of the road where there were casuarinas, the gasping man reached us. He told us to wait; boys, that it wasn’t necessary to get that far, that he could understand.

We could continue reading Valdés, but, please, he said, we should do it discreetly, that is, disguising the subversive material, wrapping it in a sheet with the periodic table or at least the daily Granma.

One or two years later, I became a journalism student and doing my professional internship, a radio sound engineer friend in Holguín more or less told me the same thing. That’s why I didn’t put a cover on that book I was reading. Then, I thought about the mania of all those people who wanted us to cover the books. They looked like masters of sleight of hand or vendors at a shop selling clothes.

The book was Tres tristes tigres (Three Trapped Tigers) and I do not know how he knew it. Not even a letter on the cover suggested a name. The cover with which it left Caracas had been subtly discarded by its previous owner so that no one would know what it said.

And the minister of culture, Prieto, who had said to some students at a meeting that Cabrera Infante was not censored because he was in all the university libraries.

Rightly so, the government had bought the collection of the Ayacucho Library in which TTT was included, only that in most places it was missing, not because it had been confiscated in customs or the censors of anything subversive, but because these, or relatives familiar with the subject, appropriated the vetoed materials to swell their personal library.

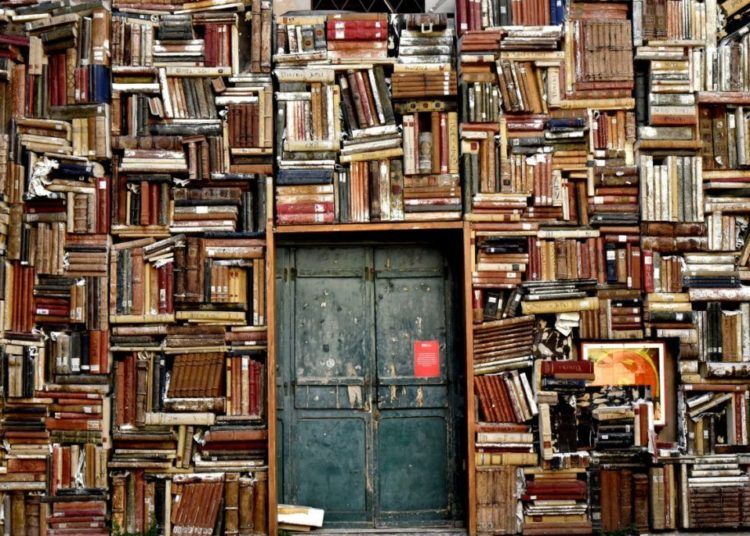

Much later, I found books by blacklist authors even in state bookstores. But that they were there, at the beginning of this century, even today, continues being an exception. And such a finding continues to represent an eternal blunder in the happiness of readers.

In university I used to chase after the forbidden books or authors with adrenal vehemence, and I would torment the bookseller I used to find by reciting titles by Vargas Llosa, Milan Kundera, Bulgakov, Padilla or Norberto Fuentes. The effect was stares of amazement that resulted in monosyllabic conversations. Because the simple fact of talking about certain authors could be as problematic or, at least disturbing, as reading their most seditious works.

Censorship has deranged people, has left atrocious psychological consequences and very rare manias in all of us who have suffered it. I remember that bookseller near Infanta and Zanja streets, in Havana, who, with my back turned to him, be it from his small living room turned into a bookshop, in the hall shouted, although his complaints were addressed to me, his most recent user: I have said nothing! You did not make me talk! Nothing!

It was terrible for me; I avoided columns and people that Saturday morning as quickly as I could, ashamed, feeling sorry for the bookseller, and for myself.