It’s already been a month since the implementation of the monetary reorganization in Cuba. Since last January 1, Cubans face a long-delayed scenario which since its official announcement in December has shaken the island’s day-to-day life and has forced state businesspeople and officials as well as ordinary workers and retirees to use a calculator.

No one escapes the impact of the reorganization in their pockets. Even though this process has represented an increase—in many cases, substantial—in wages and pensions it has also brought about a tricky multiplication of many prices, which, together with the chronic economic crisis the country is suffering and the consequent deficit of supplies, is a steep slope for Cuban families. All this, just as Cuba is going through its worst COVID-19 outbreak since the start of the pandemic.

The authorities have insisted that the new monetary reality implies, for various reasons, a rise in prices. Minister of Finance and Prices Meisi Bolaños has said that the devaluation of the Cuban peso (CUP) “leads to an increase in costs, not only at the domestic level but in the economy at a macro level”—due to factors such as the rising cost of imports, due to the new exchange rate for the State business sector, and the need to cover the new salary of workers and generate profits—, to which is added the government policy of “eliminating excessive subsidies and undue gratuities” and “stimulating work.”

Meanwhile, the government itself has recognized that conditions exist for “a higher inflation than designed”—due to the supply deficit, the increase in income and the aforementioned increase in costs—and has called for increased production efficiency and to “face speculative and abusive prices among all.” “If the price increase goes out of control, then the new wages are affected and the purchasing power capacity is lost,” Marino Murillo, head of the Commission for Implementation and Development of the Guidelines, has warned logically.

However, the authorities have explained that anti-inflationary and containment measures have been envisaged, including the centralization of prices for high-impact productions and services, and the establishment of growth limits for decentralized wholesale prices and commercial margin rates, “so that the utility, efficiency and profitability of the productions come out of the generation of wealth and tangible and material productions, and not at the cost of price increases,” according to Bolaños.

In addition, the minister and other officials have repeated that a group of basic products and services remain subsidized, in whole or in part, “until the subsidy to people is generalized,” while a set of prices “remained as until 2020 because of their impact on the population, and because, based on their social character, the need to maintain them was understood.” All of the above, they have said, implies a millionaire outlay for the State budget that, moreover, has grown beyond what was initially planned, after the readjustment—thanks to the avalanche of complaints and dissatisfaction from the population—of some of the prices and rates initially published as part of the monetary and exchange reorganization.

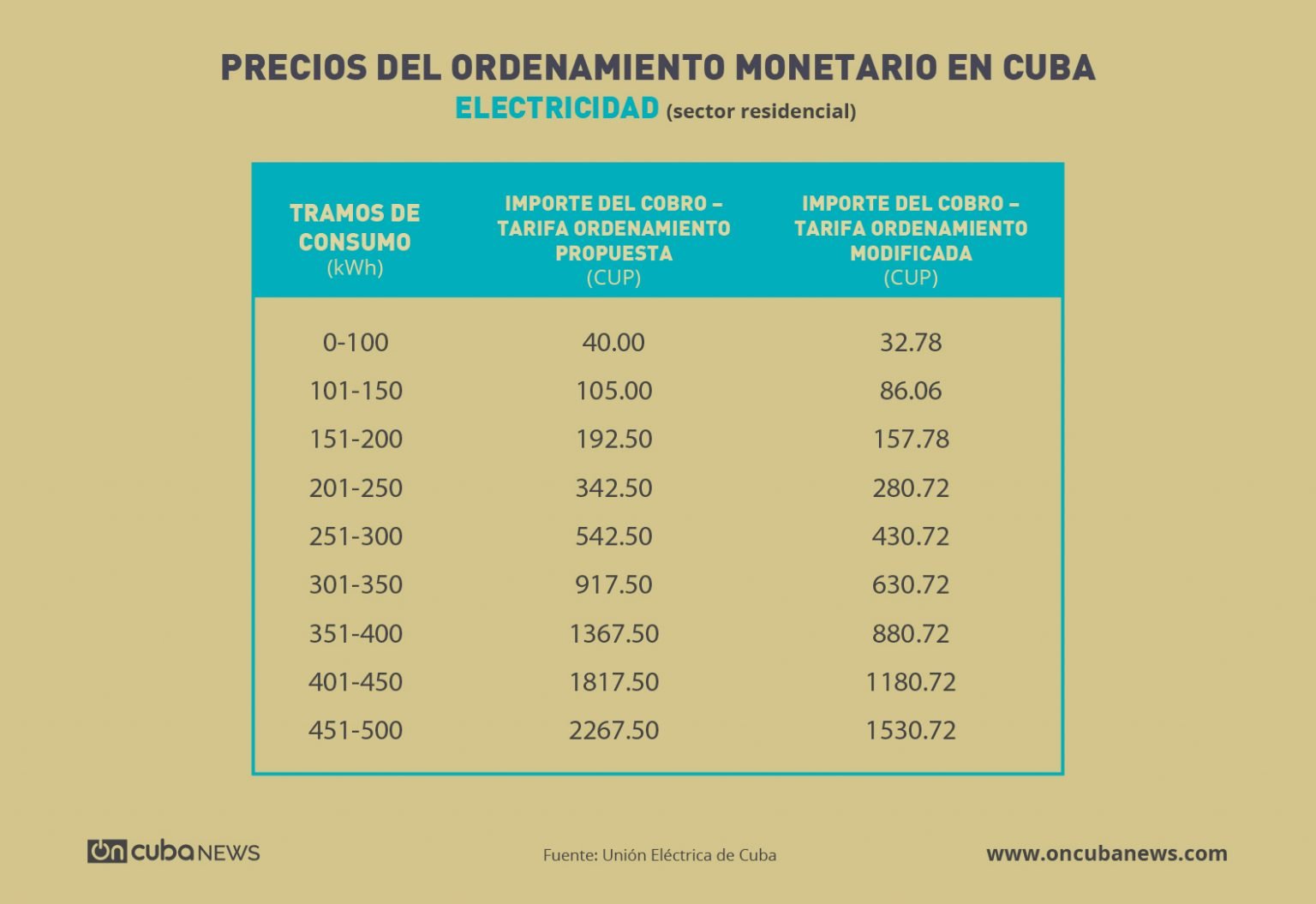

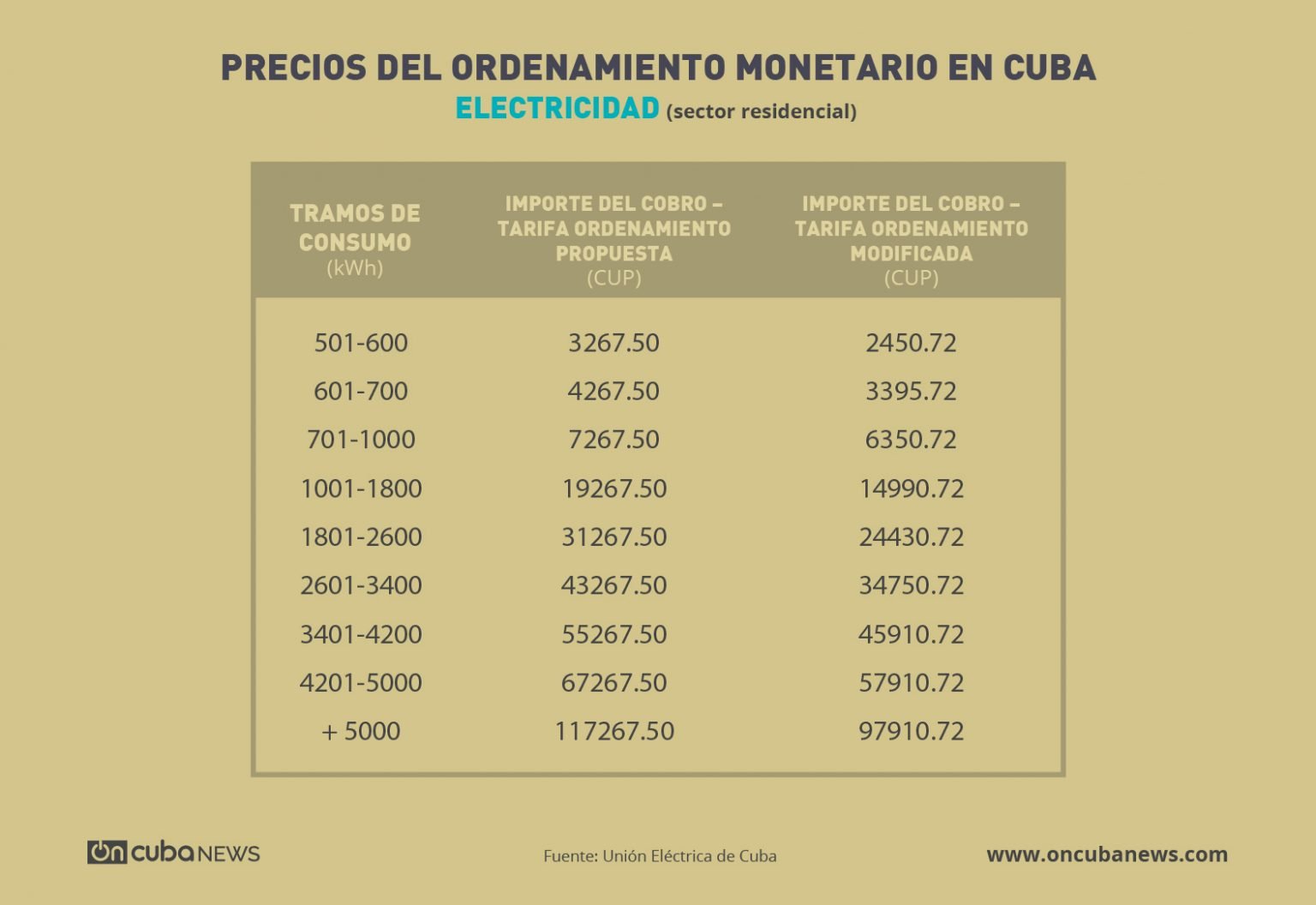

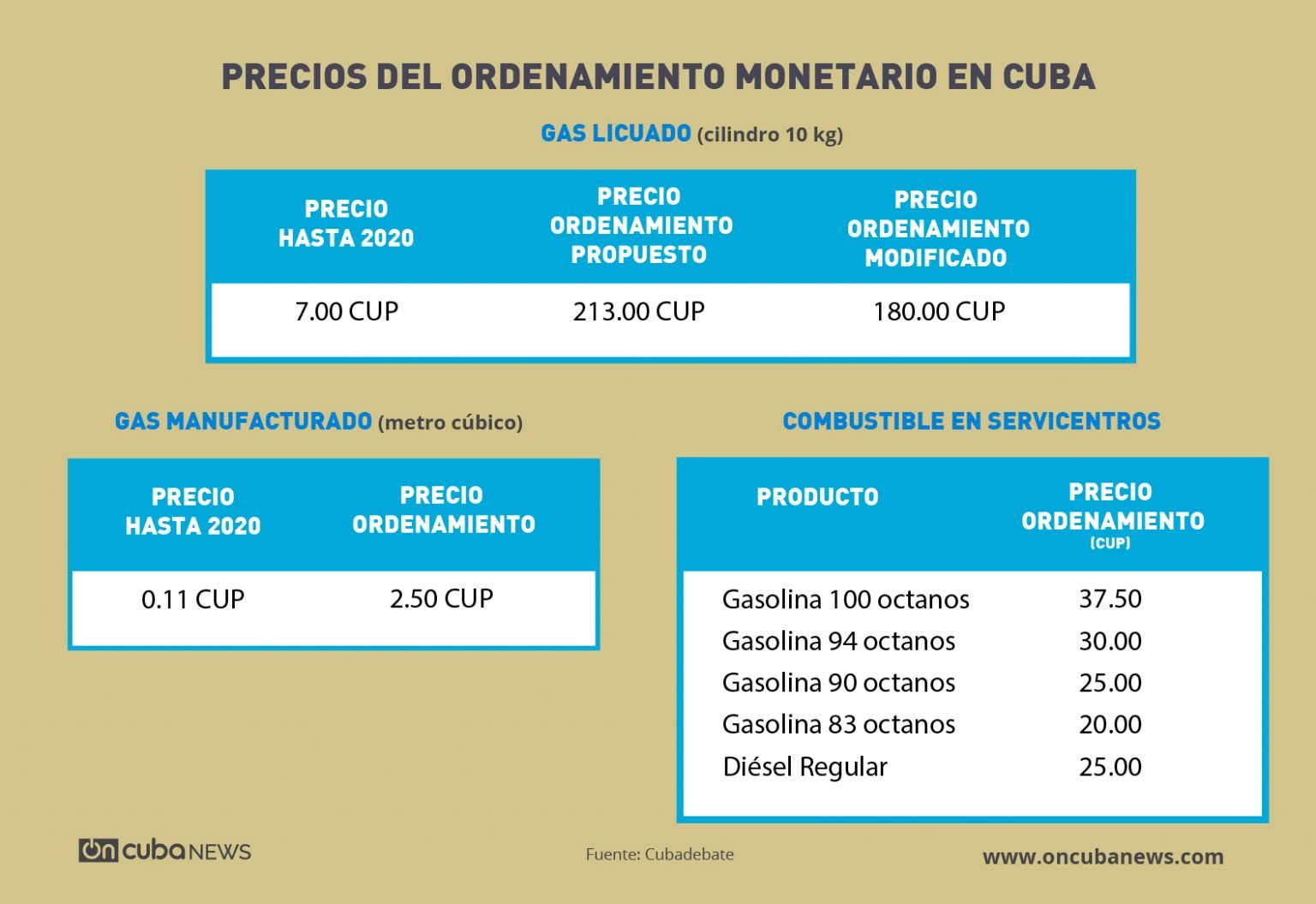

This is precisely the case of electricity rates and the price of liquefied gas, two of the issues that generated the most criticism after their initial increases were announced. Many Cubans almost hit the roof when they learned how much their expenses would rise for this concept and began to do the math with their new wages. This prompted a government review, following the premise—as explained at the time by Marino Murillo ―of correcting “what should and can be corrected,” which has later been extended to other sectors and could still cause further rectifications, as part of the work-in-progress which turned out to be the so-called Reorganization Task.

El gobierno cubano baja tarifas eléctricas tras críticas a propuesta inicial

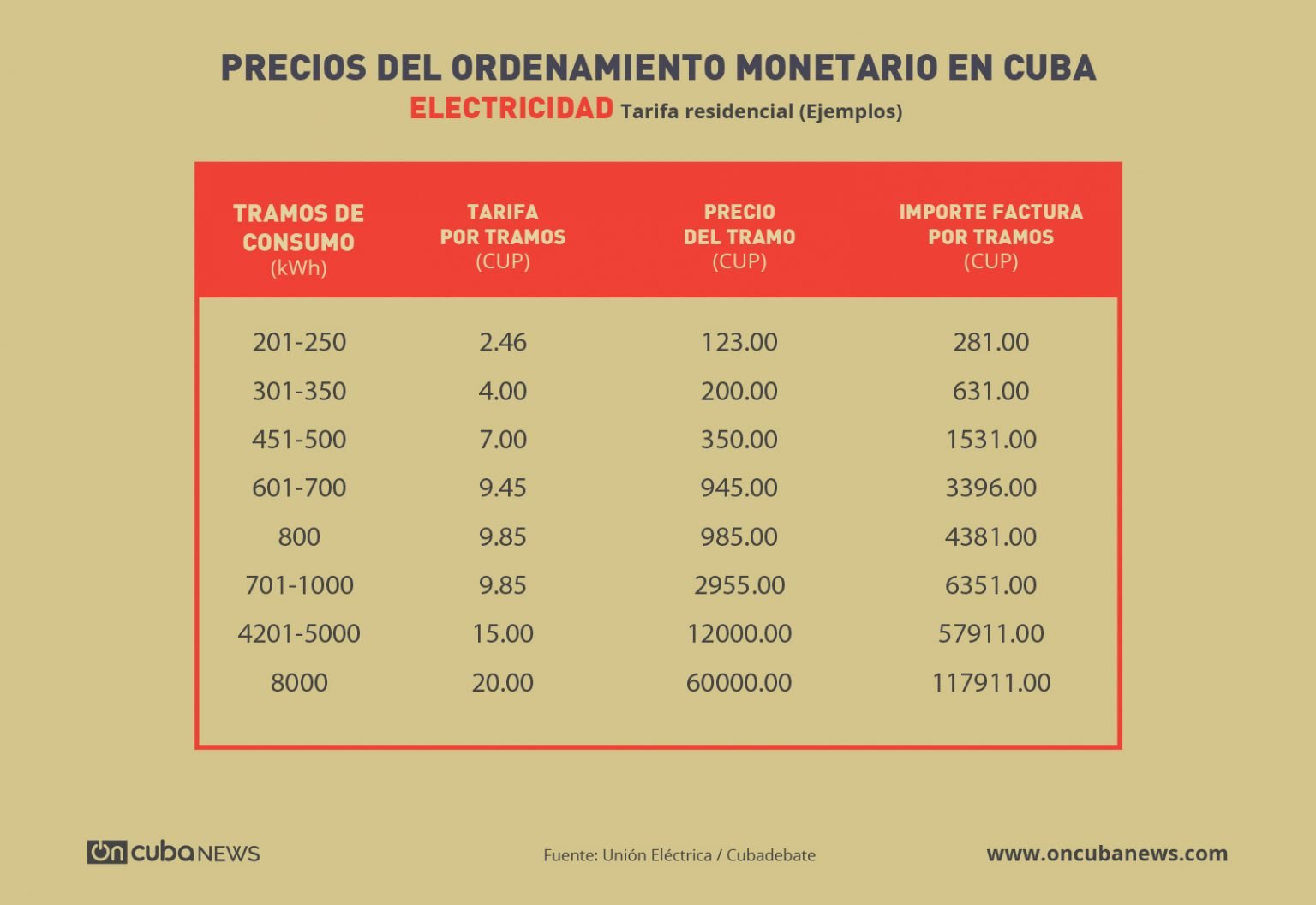

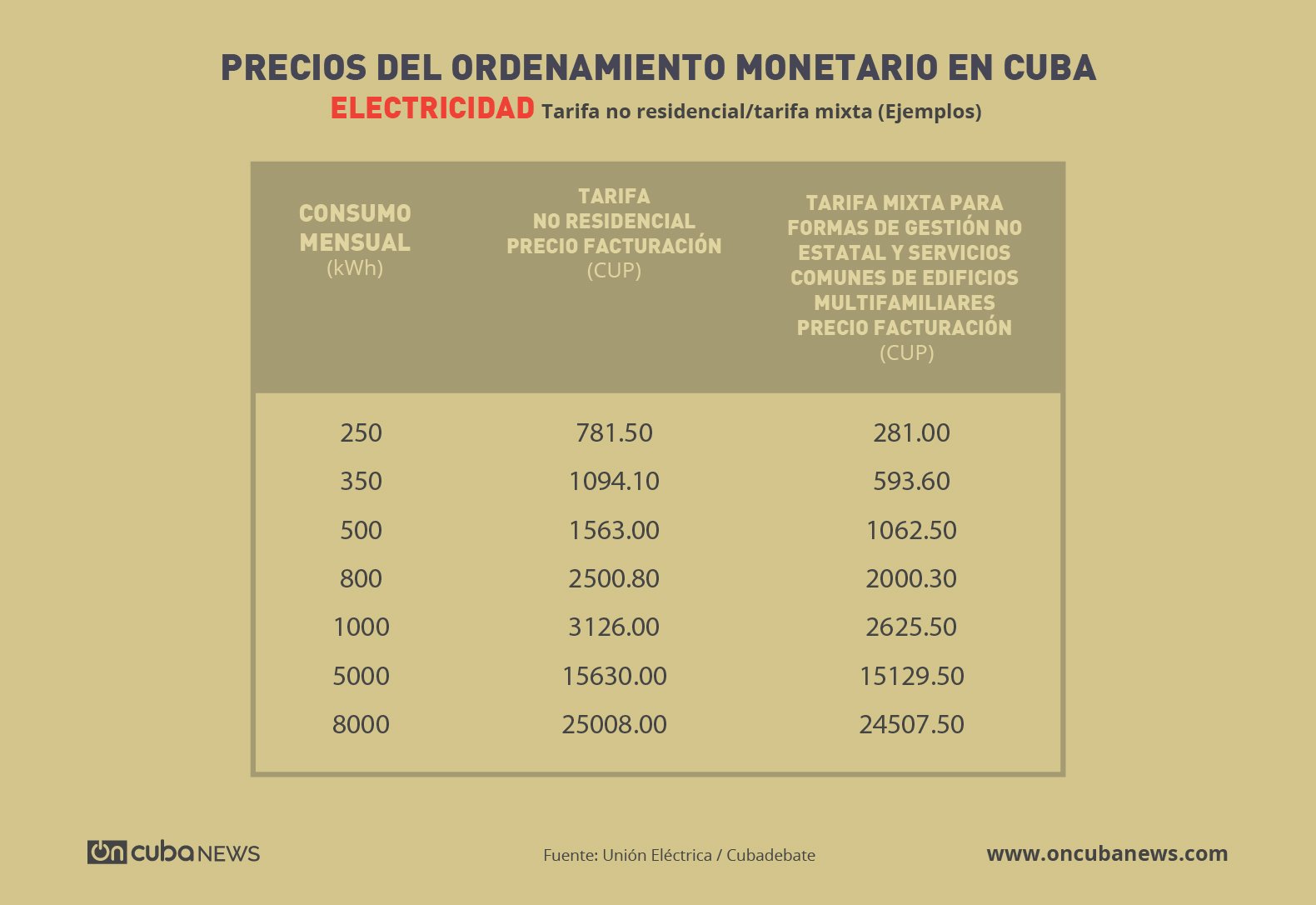

With electricity and gas, we precisely started a series of publications on the new prices in force in Cuba since last January. In this first installment we show in graphs a comparison between the electricity rates before and after the monetary reorganization was implemented, including the rates proposed and later modified as part of this process―in which the prices increase as consumption increases, with which, according to the government, the aim is also to motivate savings—as well as examples of expenses in certain consumption or consumption segments, both for the residential and non-residential sectors and in the mixed rates approved for forms of non-state management and common services in apartment buildings.

In addition, we include the prices of liquefied and manufactured gas―very widespread in Havana―, and of the fuel that is marketed in the island’s gas stations, although not including those just announced for private carriers and the state sector. And also those of the metered drinking water service—that of the non-metered service was set at 7.00 CUP per person per month, also applied to apartment buildings where individual metering by apartments is not possible—and sewerage in the domestic sector, others that caused not a few comments and that, as in the case of electricity, according to the authorities, continue being subsidized despite the significant increase in prices.

Thus, as a well-known Cuban television host says, look at the prices, consult what has been published on the subject, analyze, and draw your own conclusions.

ELECTRICITY

GAS AND FUEL

Drinking water and sewerage