December 1977

That December of 1977 would be different for fifty-five young residents in the United States and Puerto Rico, who embarked on a trip that few imagined: that of the return to their home country, Cuba, from which they had been abruptly taken when they were children, because of what their parents would consider the worst threat to humanity: the arrival of communism.

Astonishment. Reunion. Tears. Hope. Mixed feelings, hard to explain. Everything is smaller; I remembered other colors; the smell is the same…. Could you let me go up to the roof? This is the house where I grew up…. The Antonio Maceo Brigade was born.

The documentary Cincuenctaicinco hermanos, by Jesús Díaz, captures those rare seconds in which the loose ends of the universe seem to connect for an instant. Some of those who were now returning had been sent to the “north” alone, as part of the Peter Pan operation. They wonder in front of the camera, taking stock of the multiple traumas and even abuses they suffered, if all that had been really less bad than the communism that now opened the doors and welcomed them as prodigal children.

But that December was also different in Cuba: the nation wondered what to do with those who until then it had described as “worms” and “traitors to the homeland.” How to call them now? How to trust?

No matter the term used, worms, some, butterflies, others, for the first time a small crack appeared in the great wall of hate that had been rising between those outside and those inside for almost two decades.

The takeoff

That first visit of the 55 in 1977, in which members of the Areíto and Joven Cuba magazines would participate, gave rise a year later to what is known as the 1978 Dialogue, which was followed by the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Conferences of the Nation and Emigration in 1994, 1995 and 2004, respectively. The 4th will be held from April 8 to 10, 2020. The meetings, although sporadic, have marked important compasses within the complex dynamics of the government and the diaspora.

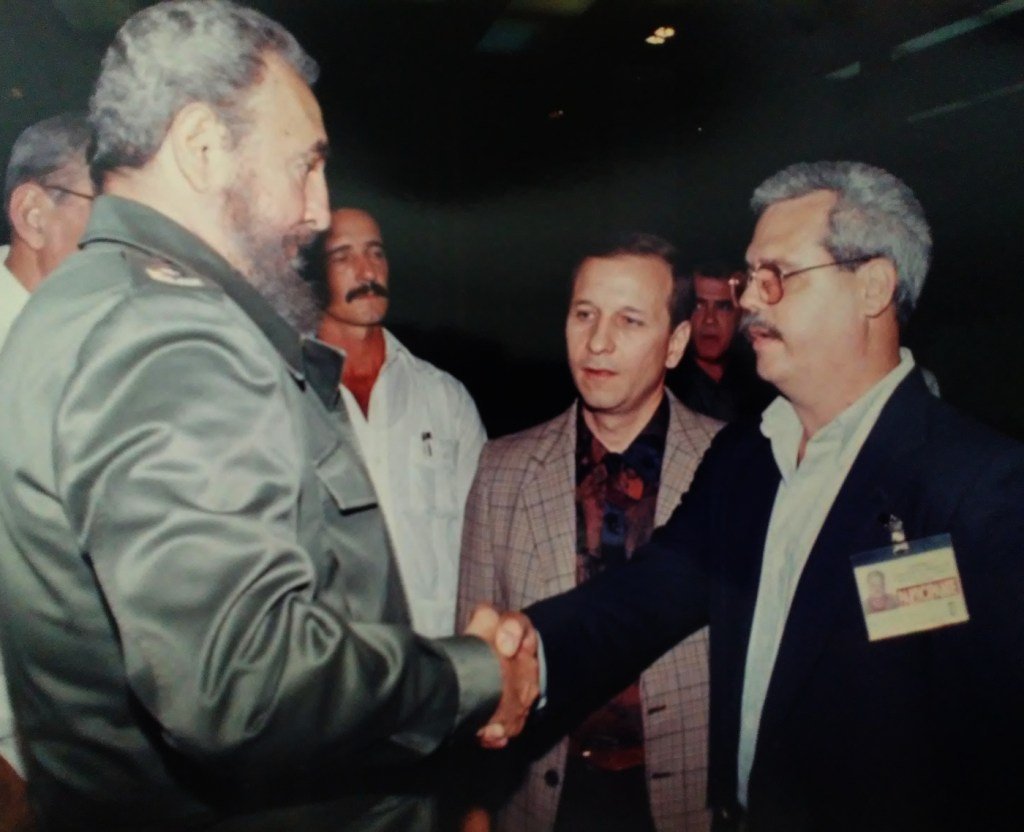

If those who had left Cuba when they were of legal age or had committed acts of violence were not invited to the meeting of the 55, the 1978 Dialogue would generate a much more picturesque quorum. With a surprising gesture of relaxed tensions, Fidel Castro would invite, in addition to the youth of Areíto, Casa de las Américas, and other pro-dialogue organizations of the diaspora, former political prisoners and Bay of Pigs veterans.

The Antonio Maceo Brigade would present in that 1978 Dialogue important claims. They requested, for example: 1) a law that would allow the recovery of Cuban citizenship; 2) cultural, scientific and sports exchanges; 3) that young people outside of Cuba could study in Cuba; 4) participation, as observers, in activities of the State, the Communist Party, and mass organizations, as well as in professional and scientific events; 5) participation in the elections of the representatives to the organs of People’s Power; 6) that the definitive return of those who so wish would begin to be considered legal; 7) the release of political prisoners; 8) that family visits be allowed; 9) that the Cuban government grant exit permits to those who want to reunite with their family in the United States.

“We believed at that time that all that was feasible. In practice it was a great utopia. We mistakenly thought we had a power of influence that was not real…. Behind all that was a whole State and a people, a people that didn’t understand what was happening…,” says Raúl Álzaga, founding member of the Brigade.

But although many of the demands, such as those related to the release of political prisoners, were produced through back channels, others were a direct result of these first claims of an emigration that knew how to place itself at a level of legitimate interlocution, beyond the violence to which they were subjected from outside; and the stigmatization and lack of confidence that they had to overcome from within.

Dynamite

Puerto Rico, San Juan. A few months before the 1978 Dialogue.

In its October 19 edition, the Puerto Rican weekly La Crónica would publish:

“Our intelligence sources inform us of the formation of a small group that will visit communist Cuba. This little group is formed and organized by one of Areíto’s communist children. We know his name, but we will only say that his surname is Muñiz. Mr. Muñiz has made countless trips to communist Cuba with Areíto’s group and his bosom friend, Raúl Álzaga.”

On November 14, the same weekly published an interview with a hooded man, whose headline states: “We will not allow the Dialogue to advance, says Z, military commander Omega-7 command: Dynamite only language with which we are going to dialogue.” [sic]

At the end of the Dialogue in Havana in December, Álzaga, upon his return to Puerto Rico, decided together with Muñiz Varela and Ricardo Fraga to form a first group of Cuban families to travel to Cuba on December 21, something they had been working on for weeks before the Dialogue. Muñiz Varela assumes the responsibility of the Varadero Travel Agency, contacting those of the Cuban community of Puerto Rico interested in traveling. On January 4, 1979, the first bomb of three that would be placed in the Agency explodes. On January 24, the Puerto Rican Senate passed a resolution condemning the Dialogue and travel to Cuba, giving the green light to the deployment of terror against Cubans interested in taking part in the trips.

Just four months later, Carlos would be shot arriving at his mother’s house. Álzaga recalls: “We were together that day, April 28, 1979…. We returned to the office of the Varadero Travel Agency at about 5 p.m. Now from the present I think they were following us ever since we went to lunch at the Metropol…. When [Carlos] was arriving at his mother’s house, he was intercepted and shot. His sister contacted us, we run there. We see the overturned car. We ask where they have taken Carlos. They tell us to the Medical Center. We go running to the Medical Center. We arrive and see that there is a room that says ‘Minimal-Access Surgery.” I say to myself, ‘Bloody hell, this bastard is scaring us for fun…now they have him in Minimal-Access Surgery and look at all our running around…. We didn’t imagine that it was so serious. From there they took him to the operating room. I got to see him alive, intubated. He died at dawn on April 30.”

Álzaga, Muñiz Varela and Fraga, devoted to boosting travel from Puerto Rico, did not calculate the extent of hatred. “We believed that all the massive support we had received from people wanting to travel gave us some impunity…we simply did not consider the consequences. If we had done so, they might not have killed him, because we had ways and knowledge of how to avoid such an attack, but we didn’t apply them because we thought that nothing was going to happen to us,” says Álzaga.

Community trips continued. But already in mid-March, Álzaga along with his colleagues from the Varadero Travel Agency, Cuba Travel (today Marazul), and the progressive forces linked to Areito magazine began to question the way in which the travel policy was being implemented.

“We got a lot of criticism; that one could go only once a year; that the hotel had to be paid, which was like 850 dollars, when nobody used it; and the problem of mass travel. That became…as if it were moving a mass of cattle from one pen to another. This was contrary to what we proposed; that is, that the trips should have more quality, less quantity, and that the political aspect should be emphasized. We wanted people to appreciate the positive aspects of the Cuban revolutionary process, which might have contributed to more normal dynamics as a result of travel. Unfortunately, it did not happen that way. The separation and differences between the two groups became greater.”

“Some modifications were made but very small. I think we lost that fight in the short term. It is only as of the 1st Conference of the Nation and Emigration in 1994 that it is possible to formalize the non-compulsory payment of a hotel to travel. The length of the stay is also extended, as well as the frequency of entry to Cuba, more than once a year. Those were our demands in 1979 and they were achieved 15 years later. In 1979 the government had two alternatives: the first—the one we proposed—to explain to the people why this situation occurred, those policy changes towards these people who had been enemies until the other day; that is, prepare and educate the people for that; the second, see travel as a source of economic income at a time when the country needed it. I understand why the second was chosen. Seek as much money as possible.”

The Muñiz Varela case, although it was one of extreme violence, is far from being the only one. Omega 7, CORU and other terrorist organizations in exile would carry out countless attacks that would cost the lives of several Cubans in the diaspora.

What followed

The efforts of rapprochement between the diaspora and the Cuban government did not stop. The 1978 Dialogue was continued in the 1st Conference of the Nation in April 1994. As a result, the creation of the Department of Attention to Resident Cubans abroad adjacent to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was approved, which would later be named Department of Consular Affairs and of Cuban Residents Abroad (DACCRE). Hotel requirements would be eliminated thanks to countless efforts by Álzaga and others. Also, as of that date, the prohibition of the return to Cuba of the “Marielitos” was eliminated.

In the 2nd Conference of the Nation and the Emigration of 1995, the so-called travel validity, a multiple entry permit to the country, was introduced, which prevented carrying out new procedures each year. It was also authorized that young Cubans residing abroad could pursue university studies in Cuba as part of a non-free program, and recognition of the right of Cubans residing abroad to invest in Cuba was established.

In the 3rd Conference held in 2004, the entry permit would be eliminated and the passport authorization would be instituted.

As of January 2013, the immigration reform enabled the elimination of the white card and the mechanism of the Letter of Invitation. By 2017, the authorization in the passport would be eradicated and the entry to and exit from Cuba in pleasure boats of Cuban citizens residing abroad would be authorized. Likewise, the permission to enter the country of Cubans who had left illegally was established, with the exception of those who had done so through the U.S. Guantanamo Naval Base.

There have been considerable advances. It is obvious that at all levels, relations between the government and the diaspora have been moving towards a stage of greater stability and functionality. This responds to a political (and pragmatic) will of rapprochement by the government, but also to the existence, from the beginning, as the case of the Antonio Maceo Brigade demonstrates, of a diaspora interested in promoting engagement positions, paying even with many lives, because of the belligerent behavior of a part of the exile.

What else can we do?

The Cuban diaspora in the United States then arrives at this 4th Conference of the Nation and Emigration with new challenges and new rights. In the current context, with an administration that threatens to last four more years in power with a radical anti-Cuba agenda, we diaspora Cubans ask ourselves how we could not only cushion its impact, but develop new engagement patterns with a direct benefit in the country’s economy, beyond the blockade and Trump.

“I think the country has grown,” Fidel said as a corollary to that first meeting with the 55, in January 1978 (usually paraphrased as “the country has grown”). Undeniably, the country grew. But has this growth been continuous? Has it been full? What course has it taken? What is meant by growing, when basic everyday issues become, again and again, an odyssey? In what areas can the country grow more? We believe that a more flexible and creative approach to the following topics can contribute to this.

Migratory issues

One issue on which the diaspora continues to insist is that of reducing the price of passports, ours being one of the most expensive in the world for Cubans residing in the United States. It has two forced extensions that involve an additional expense, adding up to 695 dollars, including the issuance of a new passport and extensions (excluding agency costs).

Why not eliminate extensions? In this way, we Cubans could have a greater incentive to travel. This would in turn ensure a more constant and fluid participation by emigrants in dynamics of circular and transnational migration, with performances with greater importance and scope in the economic life of their country of origin.

Economy: investments, training, mental blockage

Despite the new restrictions on remittances and travel, and that some people who spend the night in Miami want to grab the baton of hatred in order to get positions paid by the Helms-Burton or YouTube ratings, the figures show that both remittances and trips have been maintained. In 2018 alone, the amount of the first amounted to 3.691 billion dollars. More than 600,000 Cubans visited the island in 2019 (a slightly higher number than in 2018), despite Washington’s sanctions.

However, despite the fact that the remittance market to Cuba has become the seventh largest of its kind in Latin America (only surpassed by Mexico, Guatemala, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Colombia, and Honduras), the Cuban government has not been able to take full advantage of this. Perhaps because it remains to be understood that it is not only the amount of remittances that counts, but what is done with them. As in the case of the 1979 trips, it is not only about the quantity, but about the quality of the process.

“Many obstacles”

Jorge Artiles is a repatriated Cuban-American who has resided in Havana since 2016. He left the island for Miami in 1994 when he was 15 years old. For years he has explored ways to reconnect with his country. Since 2008 he has been involved in the cultural exchange between Cuban artists on both shores. Now, he is trying to boost his own electric stroller business because these, “in addition to having become an efficient alternative of ecological transport, resolve a great deal in countries with transportation problems, either because it is scarce or because there is a lot of traffic.” However, Artiles complains that “there are many obstacles.”

“As a result of the public transportation problem in Cuba, I had the idea of getting the recreational transport license (electric bicycles and strollers), but it was suspended. I went to the enterprise that regulates transportation in my municipality, Centro Habana, and they don’t give me real reasons why they suspended it. I can employ up to ten persons and help with social security, since as an employer and contractor I pay social security taxes, and in addition, employees also pay their taxes, but everything is simply an obstacle….”

What’s the sense in canceling a license in an area of so much demand?

“When I ride through Old Havana, even the tourists stop me and ask me where they can rent them. Then I thought about importing professional electric charging equipment for ecological transportation like in China and all of Europe, but before I found out about getting a license for fast charging points for motorcycles and electric bicycles, and they told me that they also don’t give a license for this type of self-employment. Any retiree could receive extra money by having this small business in their home, but everything is an obstacle.”

Artiles also took out his Real Estate Advisor license for buying and selling properties. Neither has he been able to set up that business. “With that real estate license I can’t hire people. It has to be only me. I can’t have a secretary or someone to help me in the business. What if I am inspecting a property and a customer calls me to see another property? I wonder if we could then use our experience to teach how things are effectively done in other places.”

The best ally: experience

Let’s reflect. Has the person who drafted the license for buying and selling real estate ever had a real estate business? Wouldn’t anyone who decides to open a real estate business benefit from the advice of someone with experience in that field? We know that Cubans are creative, enterprising, intelligent. However, times are pressing and experience can be our best ally.

In the United States, companies, academia, and private and state-owned enterprises develop training to share lists of best practices based on the experience of the sector in question. Why not make use of this logic of “best practices” for the benefit of setting up enterprises in Cuba like the ones Artiles wants to develop? He would be a perfect candidate to give these workshops. As he tells me, he would do it with the best disposition. “Not everything is for profit,” he says. “For many, the development of our nation is a priority.”

Another related issue is that of the possibility for non-repatriated Cubans and foreigners to buy property.

“I would like to suggest that they consider, as a way of attracting foreign currency in the real estate sector, that a Cuban born in Cuba without an identity card, or a foreigner, can participate in the purchase of a home, either as an owner or co-owner, as in any part of the world and, since he is not a permanent resident in the country, he is charged annual taxes on that purchase in freely convertible currency (MLC). That money would also serve to help the housing development for the neediest population, just as the sale of cars in MLC will supposedly help urban public transportation in the country. It is also necessary to develop online access to appointments for procedures related to housing. It would speed up the endless lines in the crowded law firms that can’t cope with all the work.”

Artiles insists that there is too much mental blockage, too much misinformation about the forms of relationship within a mixed economy model, to which people are not used to. “This is not born of a lack of disposition, but of ignorance, since they were years with a Soviet-style, vertical economic model.” And he adds: “if the blockade from abroad exists, that of the inside, that of bureaucratic obstacles and bad habits; that of not knowing that a client is always right and that the client must always be treated with respect, that type of blockade exists as well, and it is very bad….”

The diaspora could collaborate by offering seminars, workshops and training in which Cubans, from both here and there, would develop together brainstorming that incorporates strategies from both sides: from outside, the experience of best practices; from the inside, creativity and knowledge of factual aspects related to the demographic of markets, for example.

But for all this it is necessary to finish unblocking the granting of legal status to Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), both for Cubans on the island and for emigrants who want to invest.

It is already known that under Law 118 there is no distinction on the origin of the investor. However, experience has demonstrated that in practice, the areas of state investment are not attractive to the average Cuban, since they require large amounts of capital.

In addition, those capitals of Cubans residing abroad are already being mobilized in very precise areas such as food, transportation and rental businesses. According to Cuban economist Pedro Monreal, these investments already exist, without a law that protects them.

How to understand then that within the crisis being experienced, the Law of Enterprises that regulates SMEs will not be discussed until 2022, according to the legislative schedule? That the Law of Monuments and of Copyright has priority over the one for Enterprises, especially considering four more possible years of Trump government?

In Latin America, SMEs play a fundamental role in the economic performance of countries. They are a considerable source of jobs and contribute significantly to the GDP, bringing together a high percentage of enterprises operating in industry, commerce and services.

Cuba must give priority to the medium private enterprise, first of all, giving it legal status. In this way, nationals could begin to invest in areas asking for capital injection. The diaspora, in turn, would see in this an incentive to promote the lifting of the embargo/blockade, which would give it access to that market of which nationals would be part.

For this, the logic of convoluted and excessive regulations that, far from motivating the investment, slow it down and discourage it must be replaced. Only in this way could three fundamental aspects that damage the development of the Cuban economy be reversed: the erosion and underutilization of capital that arrives on the island in remittances; the massive departure of people who emigrate; and an atmosphere of distrust that discourages investors.

***

Cubans residing abroad had the possibility of participating with comments (not anonymous) in recent debates for the new Constitution of the Republic. Steps like these are important, but the demands of the Antonio Maceo Brigade to have “participation in the elections of the representatives to the organs of People’s Power” are still a pending dream. This demand is over 40 years old now. It is time for it to be considered.

For the country to really grow

The Cuban economy is going through a difficult time, within a context of regional radicalization of right-wing forces and the possible extension of current U.S. policy. The conditions are terrible, but the power to improve them is in our hands, removing many of the obstacles that prevent us from moving forward. The diaspora can play a more proactive role in it than it has had so far. There is no time to lose.

We are not only useful for remittances. If we are given the opportunity, we can give them a truly fruitful use: creating jobs, promoting new professions, making the country grow in a true pragmatic dimension and of common benefit.

All Cubans deserve it. Those inside, who have gone through too many years of hardship and sacrifices; those from outside, who, by defending dialogue and normalization, have been subjected to real and virtual threats. Those like especially Carlos Muñiz Varela and others who, like him, paid with their lives to give the diaspora the place it deserves, in the heart of the nation, deserve it. Let’s hope that the 4th Conference of the Nation and the Emigration is really an opportunity to reflect on it.