Vedado was created around the mid-1800s, as Havana’s continuous and systematic expansions revealed a city that had spread and become populated beyond its ancient walls, all the way to what is known as Belascoaín street. The undeniable novelty of Vedado’s design would contrast with the 19th century urban planning that had become established in the Cuban capital.

The first project for a neighborhood (dubbed El Carmelo) was presented to city authorities in 1859. It was outlined around a hacienda very close to where the Almendares River empties into the sea. The following year, and in line with the same ideas, an adjoining farm, known as El Vedado, was divided into plots. Its name (Vedado means prohibited area) came from the restrictions (on production and construction) that existed along the coast for defense reasons. In the end, these two development projects and others nearby, in subsequent periods, were unified under the single name of El Vedado.

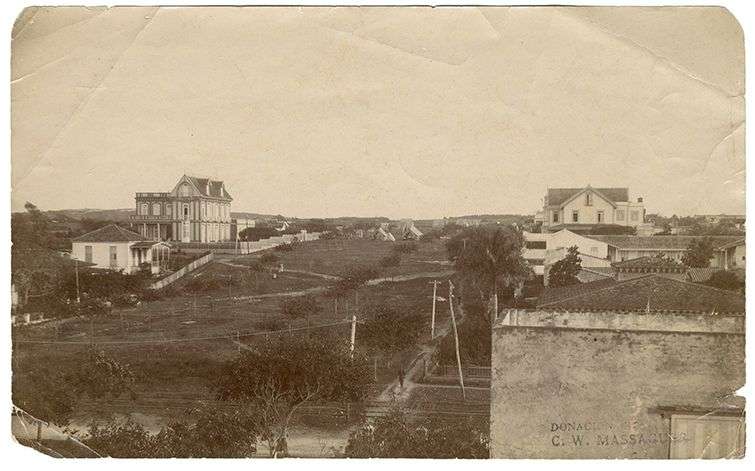

The proximity of this area to Havana’s shoreline, and its rugged slopes, helped to make it a visually diverse landscape. One decisive element contributing to the uniqueness of this neighborhood was its urban layout, which was turned at a 45-degree angle in its geographic orientation to the rest of the city, with the goal of benefiting as much as possible from the ocean breeze. Another novel element was the planting of trees on streets and promenades and in city parks, as a way of counteracting the rigors of our climate. And the design of its streets (with wide roads, sidewalks and parterres) would in later years easily assimilate the arrival of the automobile years, as well as ensure access to the rest of the established city, from which it was separated by several miles of undeveloped land.

Another novelty was the practical method of using letters and numbers for street names. On one of the main streets, the popular “maquinita” (little machine) circulated, a form of public transport that was initially steam-driven and then, by century’s end, electric. That little trip down Nueve street (which is while it was dubbed Línea (“Line”) ended at the district’s westernmost point, at Carmelo Station.

Another novelty was the practical method of using letters and numbers for street names. On one of the main streets, the popular “maquinita” (little machine) circulated, a form of public transport that was initially steam-driven and then, by century’s end, electric. That little trip down Nueve street (which is while it was dubbed Línea (“Line”) ended at the district’s westernmost point, at Carmelo Station.

The gates and front gardens required by the urban design contributed to coherence in the resulting image, which was favored by the excellent architecture used in the area’s blocks, independently of the variety of building types, formal expressions and hierarchies.

The district’s early decades saw a slow pace of construction activity, a consequence of the military conflicts and insecurity that reigned in the country. Nevertheless, some families from a certain social range began to settle down in this promising area, their homes initially coexisting with the humble dwellings of fishermen and settlements of quarry and gravel workers. The new residents benefited from the low prices of the parcels for those who built quickly. Given the area’s proximity to the ocean, some houses were built as summer homes, and incipient guest housing was constructed as well along with simple buildings associated with swimming holes along the rocky coast.

The district’s early decades saw a slow pace of construction activity, a consequence of the military conflicts and insecurity that reigned in the country. Nevertheless, some families from a certain social range began to settle down in this promising area, their homes initially coexisting with the humble dwellings of fishermen and settlements of quarry and gravel workers. The new residents benefited from the low prices of the parcels for those who built quickly. Given the area’s proximity to the ocean, some houses were built as summer homes, and incipient guest housing was constructed as well along with simple buildings associated with swimming holes along the rocky coast.

In addition to the scarce number of houses in those early times, some installations for services were popular, such as the Arana restaurant, very close to the river and the La Chorrera tower, where a popular dish was served: “chicken and rice a la chorrera.” The Hotel Trotcha, on Calzada street (ruins of its façade still stand), was known as an excellent meeting place for some of the most important celebrities and visitors of the period.

In the early 20th century, when the Republic was established, construction activity increased notably: a group of Liberation Army former members who were given compensation payments invested in the area, building splendid residences. These included the generals Enrique Loynaz del Castillo, Emilio Núñez, Juan Rius Rivera, Col. Domingo Méndez Capote, Lt. Colonel Aurelio Hevia, and others.[1] At the same time, other new arrivals included high-income professionals, merchants, European immigrants, and Americans who were involved in the occupation government, some of whom later remained, motivated by the country’s growing economic activity.

The neoclassical expression that prevailed in the architecture of these spacious and comfortable early residences, and their painstaking construction, were decisive to their attractiveness. In general, they were one-story homes and the composition of their designs maintained a logical relationship with the traditional architecture found in other parts of the city. One part of these continued using the rules of party walls (the shared use of a wall or a wall between two houses), giving way to rows or strips of adjoining homes along parts of certain streets (for example: Calle 15 between Paseo and A, and Calzada between D and E), with their indispensable gates and gardens. Others took advantage of the possibility of isolating themselves toward the center of their parcels, surrounding themselves with passageways and gardens, doing without an interior patio and ensuring ventilation through the perimeters. The casa quinta (or “country house”), which had been developed much earlier in Cerro district, provided a model in that sense. To a lesser extent, some buildings reflected construction solutions that had nothing to do with our climate, deriving from U.S. influences that were being felt.

Some valuable examples of Vedado’s earliest residences still stand, especially on the westernmost sections of streets where the district began to flourish: Calzada, Quinta (5th), Línea, Quince (15th), Diecisiete (17th). Most of them are in a constant battle with deterioration, while others, especially frame houses, have disappeared. Only a few of the latter remain, such one located on 21 and D.

Vedado’s repertoire changed over time. Many homes were made larger or modified, according to the social and economic situation. Others were replaced with more contemporary buildings. The natural deterioration that comes with time or with a sustained lack of maintenance presented further dangers, as did real estate speculation, unfortunate changes of building use, and unregulated construction. Given the changes underway in Cuba today, technical consultation is essential so that every change made to a building will bring the desired recuperation—something that is already being seen, in some cases. The challenge is to preserve the variety and richness of this assortment of buildings with a high degree of heritage value, built in an area that brought with it a beneficial change to the traditions followed until then in Cuban urban development.

[1] See Llilian Llanes Godoy: El Vedado de Generales y Doctores, Selvi Ediciones, Valencia, Spain, 2013.