If Steven Spielberg were to take a trip to Cuba these days―if he could do it even in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic―he would surely film the second part of Catch Me If You Can, that so-much-liked film based on the life of famous swindler Frank Abagnale Jr. that Leonardo Di Caprio and Tom Hanks starred in 18 years ago. Only instead of narrating the persecution around the world of the elusive Abagnale by a stubborn FBI agent, its sequel would take place mostly in a digital environment and would reflect the countless vicissitudes of those who try to buy the different products that Cuban online stores sell today.

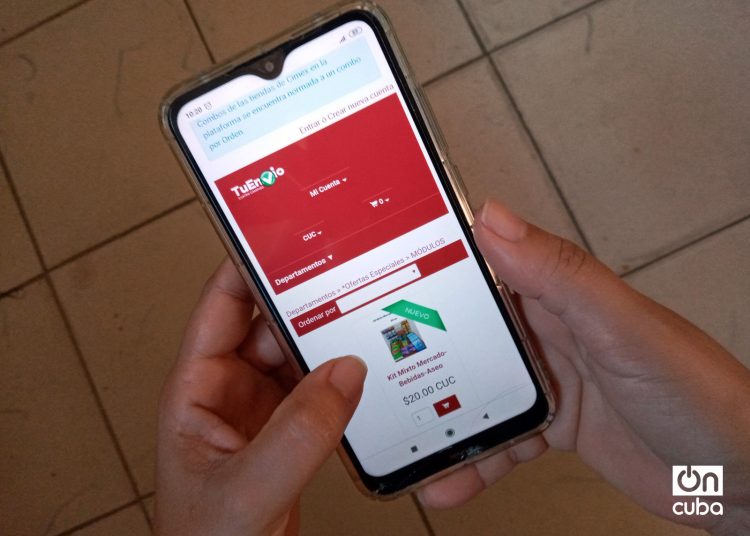

At least this is what Ihosvani thinks, “a movie buff for pleasure and a buyer out of necessity,” one of the many and many Cubans―I wouldn’t dare risk a number―who dedicate part of their days to monitoring the different online shopping platforms that exist on the island, mainly the controversial TuEnvío, of the state corporation Cimex; to monitor notifications and alerts for mobile applications and groups on social networks; to navigate the not infrequently stormy waters of connectivity in Cuba; and to “hunt” any “prey” that appear in one of his systematic forays into the internet.

He and his wife Mabel alternate in these tasks, carried out alongside their respective professions―he is a computer scientist and she is a lawyer, and they have worked mainly at home in the Havana municipality of Cerro since COVID-19 arrived on the island―, the housework, and the upbringing of their four-year-old daughter, which, according to Ihosvani, is the main motivation for their online safaris, since they can’t conceive of the possibility of being infected―and then passing it on to her―in any of the tumultuous lines that are part of the daily lives of thousands of Cubans these days. They, thanks to their own income and “the little help” from their family in the United States, keep their mobile data active and are part of an army of less visible buyers, but no less effortless than their peers in the physical universe.

Buying in Cuban online stores requires patience and perseverance, but also some luck, Ihosvani said to OnCuba. Nevertheless, he explains that it is important to have a strategy to not leave everything in the hands of chance, as well as being flexible to learn and evolve along with the operation of the platforms, which he still considers are at a primary stage compared to the rest of the world, although “little by little they seem to be catching up.”

His opinion, he says, is firmly supported by experience, because like many Cubans he ventured into this adventure last April when Cimex announced the expansion of its online sales with the aim of “making purchases possible and avoiding crowds in commercial establishments” at a time when the island sought to stop the increasing transmission of COVID-19. From that moment, although he managed to make several purchases and did not have, he claims, the same bad luck as others, he did suffer as many failures and inconsistencies in a service announced with great fanfare by the trade authorities on the island, and that very soon became a sharp boomerang that sparked not only numerous complaints from its customers but also criticism from the government and the state press, to the point of being described as “a stone in the shoe of the computerization of society.”

TuEnvío’s difficult road

The history of electronic commerce in Cuba certainly did not begin with the pandemic. Its implementation is part of the strategy of “computerization of society” that President Miguel Díaz-Canel has turned into one of the flagships of his government management. However, until the coronavirus landed on the island and forced a group of measures to be taken to prevent a rapid and catastrophic spread, hardly any discrete steps had been taken, with little social resonance.

To the already possible purchases for Cuba from abroad, the online sales services of the 5th and 42nd Shopping Center of Havana, belonging to the Cadena de Tiendas Caribe chain of stores―and pioneer of its kind of a state entity for Cuban buyers―and the Super Fácil platform, from the CITMATEL company, had been timidly added at the end of 2018. A year later TuEnvío would start, first in the Cuban capital and then it gradually spread to the rest of the country, until the coronavirus put the issue on the foreground, and soon the controversy flared up.

The Cimex platform, which had arrived last, quickly had the spotlight aimed at it after the announcement that the already Carlos II online store would be joined by others in Havana, such as the Mercado de Cuatro Caminos and El Pedregal, in addition to those in each province, in which only “identified basic need products would be sold, in the approved quantities” and prioritizing home delivery―for which the transportation of the Correos de Cuba postal enterprise started being used first and then a taxi service was added―, at the same time that the chain’s large shopping centers closed their doors as part of the measures implemented to deal with the pandemic.

The alarms went off immediately. The first customer complaints were related to the very possibility of accessing the platform, registering and being able to buy. Almost immediately the criticism would turn into an avalanche and the initial illusion would collapse like a house of cards.

The repertoire of complaints would grow rapidly to include phantom purchases, in which money was discounted, but the order was not reported; the incoherence between the physical and online inventories, which made the latter mere mirages; the “mutilation” or “barter” of purchases, in which the missing or “substituted” products were almost always the most demanded; the enormous difficulties in making successful claims and getting refunds of undue discounts; the endless waits―which in more than one case went beyond the month―to receive the purchased items; and the volatility of the products on the platform, from which they “magically” disappeared at the speed of light.

Las nuevas tiendas virtuales de Cimex, entre crecimientos y desafíos

The mea culpa and explanations would soon come, both from Cimex and Tiendas Caribe―whose online establishments of the 5th and 42nd, and others that would begin to open during the pandemic, suffered a similar scenario―and from the Cuban Ministry of Domestic Trade (MINCIN). The main reason for the failures, wielded from the beginning by the managers of these entities, was the “instability” of the service due to the unusual increase in demand, an exponential increase that caused the servers of these platforms to collapse and for which, as they recognized, “they were not prepared.” This was confirmed by Héctor Oroza, president of the Cimex corporation, who in mid-May said in a television appearance that “they had not been able to foresee the growth in demand.”

Already at that time, of course, the statistics had skyrocketed. According to Deputy Minister of Domestic Trade Miriam Pérez, requests to Cuban online stores grew 16 times in April compared to the first quarter of the year. That month, TuEnvío processed more than 73,300 orders and more than 78,800 in the first fortnight of May, while in February there had been just 1,356 and about 6,000 in March, according to figures cited by Cubadebate. On the other hand, the turnout―active clients at the same time―went from barely a hundred to around 8,000 on average, which, without the technical and organizational capacities to deal with the flood, turned the platform into an online swamp for buyers and, at the same time, into a battlefield in which thousands fought for few and longed-for trophies like a package of chicken or detergent.

Such a collapse forced a first closure in stages of online stores in May, to “perfect” their management, as was said at the time. The objective was, according to what was explained, to “automate” various processes and “reconcile” inventories to optimize service and respond to the constant criticism received. However, far from improving, the situation seemed to get worse. Many of the problems that were already present were repeated again, delays and claims continued to accumulate, the availability of products was less―making efforts to achieve them even more difficult―, the times when the items appeared (and disappeared) on the digital shelves became more and more bizarre (like the early morning hours and dawns), and the reproaches continued to make matters worse.

Cuban virtual stores will close in stages to “perfect” their management

Faced with the chronic reiteration of the deficiencies, an article published on June 4 in the state magazine Juventud Técnica summed up the panorama thus: “Cimex owes compensation, or at least a public apology, for mistreatment and neglect. The online shopping platform has become a rosary of violations of law 54 of 2018, on consumer protection. Virtually every subsection has been violated. At this point, there is an accumulation of complaints, dissatisfactions and something worse: justifications.

And then came the combos

The solution by CIMEX―the company with which we tried to communicate unsuccessfully to complement this work―to the problems that its online platform continued to suffer was again the same. At the beginning of June, a new “temporary and in stages” closure of the online stores was announced to “adapt their operation” in the face of the persistence of “a group of deficiencies related fundamentally to the increase in demand.” The state corporation explained then that “along with the country’s acute financial restrictions, which have significantly limited the supply of products in the network of stores, problems persist related to the performance of computer systems, inadequate completion and preparation of the personnel, insufficient transportation for distribution, deficit of areas to make orders, failures in the payment and refund processes, among others.”

Tiendas virtuales de Cuba vuelven a cerrar para “adecuar su funcionamiento”

To try to cover the hole before it got bigger, the company’s commercial vice president, Rosario Ferrer, explained that already agreed deliveries and pending refunds would be prioritized, and the official deadline for home deliveries would be extended to 10 days, although in practice it already took much longer. However, the real novelty was the announcement that after the reopening they would only sell modules of combined products, called “combos,” for 10, 15, 20 and 30 Cuban convertible pesos (CUC). The combos would comprise food and/or toiletries, and customers could only buy one per day in each store.

At the same time, the Tiendas Caribe chain also opted for a temporary closure of its online stores, such as those of 5th and 42nd and Villa Diana in the capital, “to comply with overdue orders and resolve in the system the necessary modifications to adopt new marketing measures.” Amilkar Odelín, commercial director of the chain, explained that once their stores were open they would sell modules, of which the number of options would be “depending on the availability of assortments” and the minimum price would be 250 Cuban pesos (CUP).

Reactions did not take long in coming. Clients and specialists quickly blamed Cimex and Tiendas Caribe for the obvious failures and drawbacks of the new system, although they recognized some advantages, such as the simplification of organizational and handling processes, with the possible reduction in time for delivery of purchases, something that in practice has been happening, according to several buyers consulted by OnCuba.

Professor Juan Triana, in an article published on this same site, explained that the modality of combos subjects the consumer to “the convenience of the seller” and that, like the infamous “combined products” of decades ago, they are the result of inefficiency and inability. Likewise, he listed other arguments of the clients themselves for their dissatisfaction with the new system, among them the presence in the combos of items of low demand or that buyers don’t need, but must buy to be able to acquire those of their preference, the possibility that some product of the module will not be included in it after paying due to the exhaustion of its inventories, the unresolved problems with claims, how lacerating this modality is for consumer rights, and the establishment of rigid prices, which could be excluding for lower income families.

Rosario Ferrer herself acknowledged when announcing the measure that the sale of modules “commercially is not the best option,” but said it was a “temporary” solution. Ten days later, and the reorganization process already underway, the commercial vice president of Cimex affirmed they had received “many negative opinions” about the new system, but reiterated that “taking into account the availability of products and logistics, this is what is most acceptable.” In addition, she said that the modules don’t come from slow-moving inventories, that “they are structured with what is received from imports and local productions” and that they were working on making combos “for all purchasing levels and with a greater variety of offers.”

Practice is practice

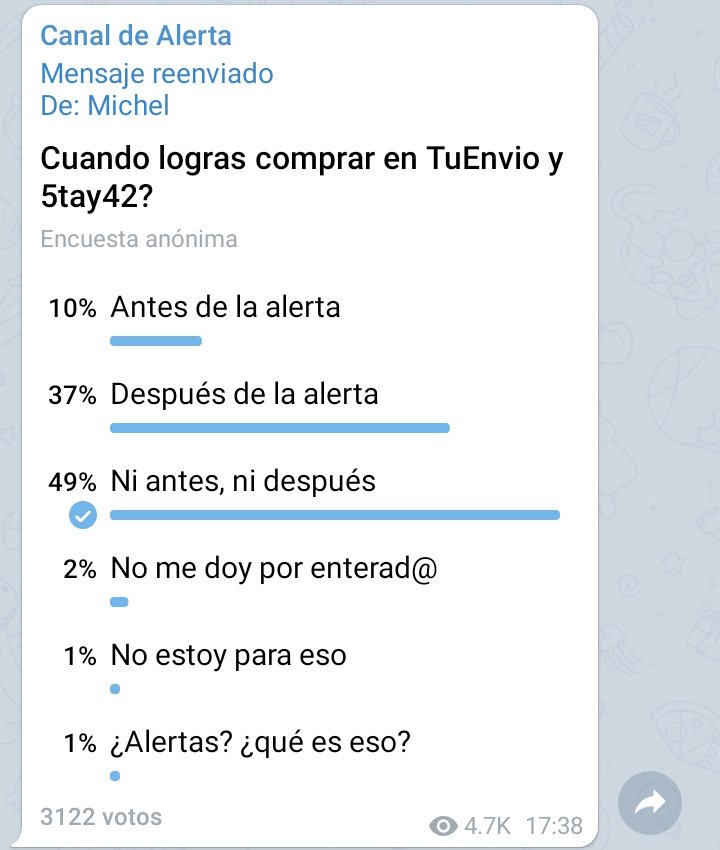

A month later, the setting for TuEnvío and the other Cuban online stores is far from perfect. Judging by the responses given by several clients and the comments published on social networks and groups on the subject that emerged on platforms such as Telegram, some of the indicators most questioned at first have improved, such as delays in deliveries and refunds, but others persist, such as the low availability of products and combos, the inclusion in the latter of merchandise not demanded or that makes buying significantly more expensive―for example, cans of tonic water, tuna fish and one kilogram packages of coffee―, the instability of platforms that “freeze” when modules with high-demand items appear―and often force Internet users to start purchasing more than once, frequently with unsuccessful results―, the mysterious disappearance of modules already placed by customers in their shopping carts before they can pay for them, and the fleeting presence of the product on online shelves, which turns their acquisition into a race against time and makes many question how real those products really are.

After the publication of the article by Professor Triana, a commentator who signed as Antonio was of the opinion that taking into account everything that electronic commerce implies, “this modality is not the solution for scarcity,” and stated that “if a part of the scheme fails, everything else is useless and leads to failure, as has happened in Cuba.” His opinion may seem fatalistic, but it coincides with many of those who over three months have come up against the same problem over and over again. For many, as the renowned economist pointed out in his article for OnCuba, citing the criteria of the clients themselves, “trying to buy makes you waste megabytes and time.” This is reiterated by a forum participant on Telegram, who summed up her bad experience on TuEnvío by saying “I’ve been using up megabytes all day to then not get anything and ending up annoyed.”

“It’s not just about money,” says Lisset from Santiago de Cuba. “It is also about lost time, the stress and the inconvenience it causes.” A friend of hers, relates this young architect, got to be up during many dawns and finally decided to give up buying at the Cimex online store because, she said, “the suffering was greater than the benefit.” She, on the other hand, although with difficulties, has already managed to make several purchases and still perseveres because “standing in lines these days is very risky and, in addition, there is the issue of the sun, which is unbearable. However, in my house, from the shade, I can buy a combo from time to time,” even when the cost is―in addition to the money―spending a good part of the day at the cell phone.

For Ihosvani, shopping at TuEnvío is still “crazy.” The most challenging thing, he explains, is “making the purchase when you discover that there is something you are looking for” in one of the stores on the platform. A combo with chicken, for example, or with hash, detergent, toothpaste, tomato puree or oil, he lists following the logic of many Cubans these days, although for this “you have to do hara-kiri and buy something that doesn’t interest you “ His methodology, like that of his wife Mabel, Lisset and thousands of other people on the island, consists of repeatedly reviewing throughout the day the sites of the online stores themselves―not only those of Cimex but also those of Tiendas Caribe―, and be attentive to the groups on the subject with which it is associated in social networks and to various mobile applications that notify you about the new offers that online stores put up for sale throughout the day.

Among the latter, he prefers the Mi alterta app, which is defined as an “independent application to keep you up to date with products on the TuEnvio.cu Electronic Commerce Portal, from your mobile in the comfort of your home” and allows its users to configure the stores from which they wish to receive notices about new products for sale―in their case, all of those in Havana, Camagüey and Villa Clara, where family members reside for whom they have purchased more than once―but he also uses Comprando en Cuba, which provides access to different online establishments and informs about what is available in them. Both are available on the Apkalis platform with recent updates and as of this Wednesday afternoon they totaled more than 208,200 and more than 47,700 downloads, respectively.

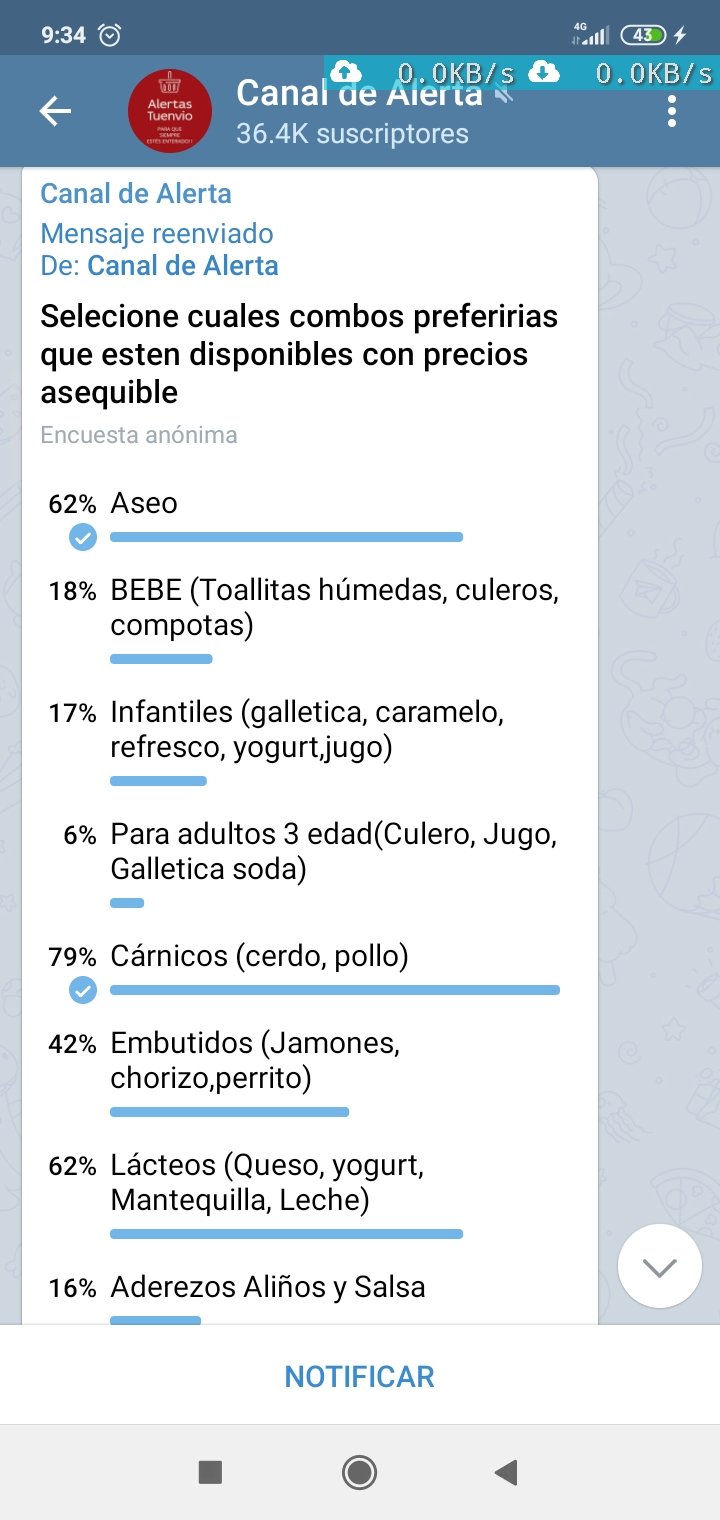

As for the networks, Ihosvany and Mabel like Telegram more and the alert channel derived in turn from a TuEnvío channel, which already has about 37,000 subscribers and in which its members report the different combos and products they discover in their persistent tracking downs through the digital mazes. It is a unique collaborative mechanism, with antecedents in pre-pandemic groups such as the already known ¿Dónde hay? and other similar ones from Whatsapp and Facebook―initially created to exchange notices about physical sales, in situ―, extended beyond TuEnvío to other stores such as those of 5th and 42 and Super Fácil, and replicated on other platforms, with variants for specific localizations ―outside Havana, provinces like Santiago de Cuba, as Lisset confirms, have their own alert groups―and other helps and benefits, such as the notice of purchases received on the TuEnvío reports channel. In this way, the odyssey becomes more bearable among all its members.

Very easy?

Whichever way potential buyers find their potential purchases, the real battle begins when they try to make them effective, when they fight hand in hand―or rather, with a broken finger, on the touch screens of their cell phones―to place his object of desire in the fickle cart and achieve the long-awaited payment without their alleged “prey” disappearing as if by magic before they can transfer the money, by manipulating the buttons on the platform as quickly and calmly as possible and continuing with luck the different steps that lead to the success or failure of their purchase.

Tiendas virtuales cubanas cerrarán escalonadamente para “perfeccionar” su gestión

There, as the famous Mexican comedian would say, lies the detail, and that is also where chance capriciously comes into play. At this point, Ihosvani jokes, “we are in the hands of fate.” Because there is no mathematical algorithm―at least he, who is a computer scientist, says he has not found it―that rationally anticipates this process, that explains why some achieve it and others don’t, while simultaneously toiling; or why, apparently doing the same thing, sometimes it’s possible to “hunt” what is sought and at others, on the point of getting it, the purchase disappears and there is no other option but to accept defeat and, instead of brooding from frustration, sharpening the senses for the next “hunt.”

“What you can’t do is give up or get too upset because then you really lose out,” he says as a good experienced hunter, according to whom a second can make a difference. “When you already have the combo in the cart, you can’t lose concentration or start doing something else, however fast it is, because you lose,” he says, and supports his statement in the fact, confirmed on numerous occasions by him and his wife, that less than five minutes may elapse between the issuance of an alert on Telegram or the app and the exhaustion of the product on the online shelf, unless the modules don’t contain products in demand or their high prices make customers doubt. And sometimes not even like that.

“Many times when you discover the alert it is not even worth trying. If it was a combo with good offers and some time has passed, rest assured that it has disappeared,” he says.

In his experience, this volatility is even greater in stores in Havana, where, according to published data, just in April, average orders per day practically doubled those of online stores in the rest of the country. To this fact, logical if one considers the high population of the Cuban capital, Ihosvani attributes having been able to buy on several occasions “in a more relaxed way” for his relatives who live in other provinces than for himself. However, this does not mean that in the online shops of the other territories the modules are always within reach of whoever wants them, like fruits that you just need to pick from the tree. “None of that,” confirms Lisset, “you have to fight very hard for them because everyone is doing the same.”

The fight even leaves the ring of TuEnvío and the Tiendas Caribe stores, to reach the Super Easy platform, of the Information Technologies and Advanced Telematic Services Enterprise (CITMATEL), which, although it doesn’t sell the same items, sells in Cuban pesos (CUP) and has some advantages compared to other stores―deliveries are much more agile, merchandise stays in the shopping cart for 30 minutes without disappearing if it isn’t paid for during that time―, it also requires its users get in the ring if they want to get their star products, at least if it’s a question of demand. So much so that some Internet users, playing with this platform’s name, call it Super Difficult in chats and social media groups.

Although due to its profile it offers Cuban digital content of various themes and formats, electronic devices, and maintenance services and computer solutions, it also sells work tools, household supplies, and hygiene and cleaning products such as bleach, descaling agents and air fresheners, all of them turned into the favorite target of many “hunters” in times of pandemic. With them, as with TuEnvío’s chicken and detergent combos, a few minutes can pass between their sale and exhaustion, and even if they can still be seen in the online store, they could well be a mere mirage, no longer being “available” or “temporarily out of stock” because someone was faster and managed to put them in their basket first.

But also with them, clarifies Ihosvani―whose wife is a regular buyer of disinfectants and other Super Fácil products―the key is to persevere. In not stopping to chase them as agent Carl Hanratty chased the young Frank Abagnale Jr. even though he was dressed as a pilot and was accompanied by a group of smiling stewardesses, and escaped again and again when he was about to be captured. The important thing, recalls the movie buff-computer scientist-buyer-hunter, is that finally the police caught the scammer and got him to work with him, and even got the famous Spielberg to shoot a movie with his story. Although with the pandemic still spreading throughout the world and the effects of its shock wave on the already affected Cuban economy, it is difficult to imagine, at least for now, a Hollywood-style happy end for electronic commerce on the island.

If, as the Cuban authorities repeat and the logic of development indicates, the online stores “are here to stay,” their present and future customers will not be able to lose patience and will power in the midst of the complex economic scenario that COVID-19 already has in store. That is, if, like the best hunters, they want to bring the most desired prey to their kitchens; if, like Agent Hanratty, they aspire to catch Abagnale one and for all.