“We’re going to do everything we can to keep Cuba on the front burner,” a senior administration official said in a call with reporters.

The verb neglect, one of whose meanings is “to ignore,” is perhaps the one that best describes the Biden administration’s relationship with Cuba, at least until July 11. A group of reasons and facts suggest this. Let’s look at them briefly.

The so-called Trump Era promoted a certain type of country and left a political-social and cultural heritage perceived by a sector of the political class as a drag on the existence of a liberal United States and diametrically opposed to those promoted for four years: they are seen as a violation of policies that have formed the hard core of historical values and behaviors, both internal and external.

Hence, the focus of the new administration was directed, above all, to put order in his own house. The extent to which this is so is expressed in that only during the first day in office, the new president signed 17 executive orders reversing decisions and policies adopted by the previous president. They were basically related to issues such as immigration, DACA, the halting of the wall on the southern border, the Keystone pipeline, the Population Census and discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation, among others, but they set the fundamental guideline during the famous first hundred days of the new government.

The first emphasis was the coronavirus pandemic. “A potential pandemic is a challenge that Donald Trump is not qualified to handle as president,” candidate Biden wrote in USA Today in January 2020. “The outbreak of a new coronavirus, which has already infected more than 2,700 people and killed over 80 in China, will get worse before it gets better. Cases have been confirmed in a dozen countries, with at least five in the United States. There will likely be more…. To be blunt, I am concerned that the Trump administration’s shortsighted policies have left us unprepared for a dangerous epidemic that will come sooner or later.”

The result was, by opposition, the creation at the beginning of the Biden administration of an ambitious plan that went so far as to propose that 70% of Americans be vaccinated with at least one dose by the 4th of July (2021), Independence Day. For a series of reasons not necessary to analyze here, that objective was not met, but in any case what was achieved up to that point sent a loud and clear message about the importance that the government attached to the fight against the coronavirus and to Americans’ health. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that by that date more than 172 million Americans — that is, about 67% of the adult population — had received at least one dose of the vaccine and approximately 156 million both doses (47%.).

But the appearance of the Delta variant made things difficult for the executive. In early July, shortly before the protests broke out in Cuba, the combined effect of this variant of the coronavirus, as contagious as chickenpox, according to experts, plus a slowdown in the rate of vaccination, began to stoke fears of a resurgence of the pandemic. By that date in the United States, up to an average of 32,387 new cases of coronavirus were reported daily, according to Johns Hopkins data. Between July 7 and 13, hospitalizations increased 35.8% compared to the previous week, according to the CDC.

Deaths also increased by 25%, reaching an average of 250 per day. Biden urged those who had not done so before to get vaccinated. “If they are not vaccinated, they are not protected,” he told reporters. “So please get vaccinated now. It works. It’s safe, free, and convenient.” That call reflected the fact that the vaccination rate had plummeted across the country. On August 6, the White House announced that half of the total population of the United States had been fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

The second step in order of priorities was assistance due to the coronavirus, that is, an economic stimulus package in the face of the pandemic, consisting basically of: a) $1,400 checks per person or $2,800 for couples filing taxes jointly (those with annual incomes of up to $75,000 or 160,000 in the case of married couples would receive the full amount; b) federal unemployment assistance benefits of $300 per week, which would run until September 6 (this figure will be added to state unemployment programs); c) restaurants and bars affected by the pandemic would receive loans of up to 10 million dollars non-reimbursable to the government if they were used to pay salaries, rents and other operating expenses; d) expansion of the fiscal credit granted by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for each child. Parents/guardians would receive direct payments of $3,600 per year ($300 per month) for each child under the age of 6 and $3,000 per year ($250 per month) for each child between the ages of 6 and 17. The parameters were the same, that is, applicable to parents earning less than $75,000 a year and couples earning less than $150,000.

The third, the infrastructure plan. In late January 2021, the new administration unveiled a plan to make a leap in the national infrastructure. In April 2021, Biden announced the American Employment Plan, aimed at spending about $2 trillion in federal funds on a wide variety of infrastructure, clean energy, research and development, and training. This included, among other things, rebuilding conventional transportation infrastructure — highways, bridges, airports, railways, and public transportation —, a program to transition from government gasoline and diesel vehicles to electric vehicles, networks, and light rail infrastructure, etc.

Renewable energy would receive around 74 billion dollars. But the plan also includes cybersecurity, another weakness of the United States in the face of the emergence of repeated external attacks (hacks). All this in congruence with the presidential campaign, which handled proposals to expand public education, health care for the elderly and paid family leave, in contrast to Trumpist policies, which would dilute the size and productivity of the workforce. Biden’s infrastructure policy would create an additional 2.7 million jobs and increase the average American income by $4,800 during his administration.

All in all, the one trillion Senate proposal, backed by the president, would funnel money toward everything, from road repairs to broadband expansion and clean energy, though its approval is not guaranteed in any of the chambers of the U.S. Congress.

As for Cuba, these internal decisions contributed to blurring it from the agenda, a result of asymmetry, that is, of the place that one party places the other in its system of international relations. In this last area, the focus has been on China and Russia, countries with which an adversarial relationship is being handled that in many ways is projected as a revival of the Cold War.

II

The previous ones were, basically, the initial hard core of the young administration. “Cuba is not something central or fundamental in United States politics, unlike the United States, which does occupy a relevant place in Cuban politics. The Cuba-U.S. dispute is real, but not the same for both sides. You just have to notice how many times senior Cuban leaders allude to the United States and how many times the Americans mention Cuba,” observed a Cuban journalist.

Ignoring it would mean leaving aside the fact that the island has been losing importance in the U.S. foreign policy system after the fall of “real socialism” in Eastern Europe and the USSR. And that for that same reason it was not a priority issue even for President Obama, who as it is known only became involved in the policy change at the end of his second term, when he had little or nothing to lose. The export of the revolution, one of the great themes of U.S. policy toward Cuba, and the status of “Soviet proxy” disappeared when the maps changed color.

But these events had another effect: feeding sectors of liberal politics and the press the idea that the conflict with the Cubans could be a thing of the past. Indeed, Cuba could no longer be a satellite of those who did not exist, it had normal to very good relations with the vast majority of Latin American governments — which left without effect the issue of the export of the revolution and the security of regional allies, two of the historical objections to normalize relations — so that the bases of the dispute would have disappeared and, consequently, it could be negotiated, especially after both parties sat down to talk face to face about the independence of Namibia and the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Africa.

The problem is that this assumption turned out to be logical, but wrong in the long run. Once the classic objections disappeared as a result of these changes, what distinguished U.S. policy towards the island was a greater emphasis on the domestic front, precisely the order that the Cuban leadership considers untouchable, arguing a problem of sovereignty. This perspective continued the characteristic preconditioning in the projection towards Cuba, now by other paths, and demanded the dismantling of the internal order to normalize things — something that, for the aforementioned reason, the Cuban leaders would never accept. That was precisely what was not done by Obama, who dedicated himself to initiating policy courses to achieve his own objectives without waiting for “signals” or “answers” in return, a new way to advance the interests of the United States.

Biden apostaría por “empoderar al pueblo cubano” si llega a la presidencia

During his campaign, Biden gave signs that his policy towards Cuba was going to follow the same path, constructive engagement; after all, he had been a participant in that perspective as Obama’s vice president. But hardly installed, in the new administration a change took place: the neglect thus came into action. Then the expression “under review” appeared, thereafter repeated over and over again. In January, Press Secretary Jen Psaki stated that “Our Cuba policy is governed by two principles, first support for democracy and human rights. That will be at the core of our efforts. Second is Americans, especially Cuban Americans are the best ambassadors for freedom in Cuba. So we’ll review the Trump administration policies.”

A senior official in the Biden administration confirmed anonymously that the president did not consider Cuba a priority, but that he did want to “make human rights a fundamental pillar of his foreign policy.” The source reiterated the same as Psaki: that the White House was committed to “reviewing the policies that were decided in the previous administration, including the decision to designate Cuba as a state sponsor of terrorism.”

But in April Juan González, President Biden’s main adviser for Latin America, made a turn when he declared to CNN in Spanish: “Joe Biden is not Barack Obama in policy towards Cuba…the political moment has changed significantly, the political space has been closed a lot because the Cuban government has not responded in any way, and in fact the oppression against Cubans is even worse today than perhaps during the Bush administration, we are very focused on various crises around the world, and also on the domestic situation.”

In the midst of this process, which suggests divisions over Cuba within the administration, the July 11 protests broke out on the island, which, like everyone else, took President Biden and his advisers by surprise. The first reaction was a resurgence of rhetoric by classifying Cuba as a failed state, an expression that mimics the codes of Ronald Reagan. “We stand with the Cuban people and their clarion call for freedom and relief from the tragic grip of the pandemic and from the decades of repression and economic suffering to which they have been subjected by Cuba’s authoritarian regime. The Cuban people are bravely asserting fundamental and universal rights. Those rights, including the right of peaceful protest and the right to freely determine their own future, must be respected. The United States calls on the Cuban regime to hear their people and serve their needs at this vital moment rather than enriching themselves,” the White House said in a statement immediately after the events.

EEUU considera imponer sanciones “contundentes” a funcionarios cubanos

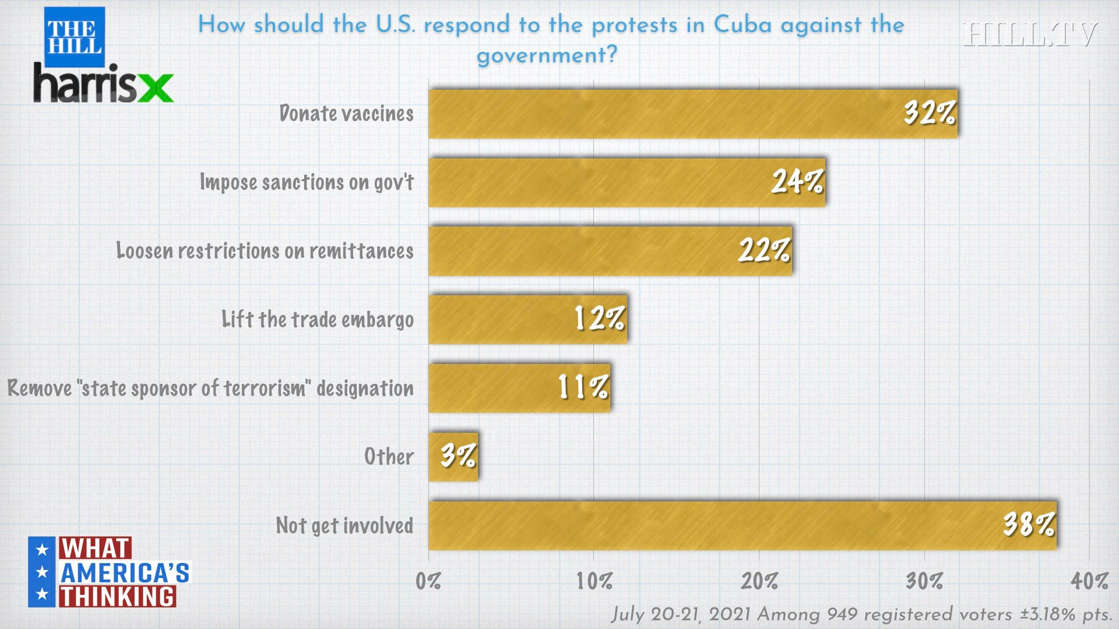

The second consisted of imposing sanctions on Cuban military and police officials and institutions, broadly announced by State Department spokesman Ned Price on July 21. The then acting undersecretary of that same Department, Julie Chung, elaborated: “We are going to focus on applying forceful sanctions to the regime officials responsible for the brutal repression. Cuban officials responsible for the violence, repression and human rights violations against peaceful protesters in Cuba must be held accountable.” From the outset, they identified Army Corps General Álvaro López Miera, minister of the FAR, and the National Special Brigade, of the Ministry of the Interior; then the chief and deputy chief of the Revolutionary National Police and the so-called Black Berets. However, the sanctions are characterized by their lack of practicality, since Cuban officials, unlike those of the Mexican elite, do not have and cannot have bank accounts in the United States, and neither they nor their relatives have gone on vacation to the United States. They are therefore limited to the political-symbolic plane, but they have had a very interesting reception beyond the enclave. A Hill-Harris poll conducted between July 20 and 21 yielded, among others, the following results:

The administration’s statements on Cuba are not, strictly speaking, actions but reactions. The administrative discourse is marked by three central themes; namely, that of the Republicans, in fact an accusation to the president of being soft on Cuba; that of the progressive sectors of the Democratic Party, which have contributed to give social relevance to the embargo by considering it one of the causes of the protests in Cuba (although without renouncing internal factors and criticism of official Cuban policies); and last but not least, that of the Cubans in exile, who have even mobilized in front of the White House to demand more energetic actions by the executive. From this framework emerges a harsh rhetoric that nevertheless falls short in a “community” setting in which intervention and annexation have once again poked their old hairy heads.

Untouched by Biden, the measures taken by the Trump administration, which according to the Cuban government constitute the basis of the problem, at least now are not going to be annulled for the simple reason that the policy of tightening the nuts seems to be giving results after more sixty years of trying the regime change. “The embargo is the matter of the United States Congress, and it is not the reason why the Cuban people are suffering,” Juan González himself emphasized. However, perhaps the main lesson of this new chapter of the bilateral relations could be summed up with William LeoGrande: “the policy of hostility is an emperor with no clothes.”