The year 2019 is considered by many analysts as the worst between Cuba and the United States in the last three years. The State Department has even admitted that it has no great interest in improving relations as long as the island does not introduce reforms and puts a stop to its alliance with the Caracas government.

When relations between the two countries were reestablished on December 17, 2014, and on March 20, 2016, President Barack Obama landed at Havana’s airport, many supporters of bilateral relations felt that there was no rolling back that thaw, which was a fait accompli. What nobody anticipated was that a New York real estate entrepreneur named Donald John Trump was going to get in the way of the fate of the two countries.

During the 2016 election campaign, Trump’s statements about Cuba were conflicting. He swayed a great deal, like a pendulum. He started by saying that he wanted a better deal with Cuba than the one negotiated by Obama. Then he said he didn’t want any deal, he flirted with the total diplomatic cut and ended up saying that maybe “we can talk with the Cubans because I’m the best negotiator in the world.”

But when he was elected, one of the first things he did was to appear in Little Havana, in Miami, and before an audience of just 700 people he said that his thing was to end the “Cuban dictatorship,” guaranteed that he was going to be “real tough” with Cuba and established a series of conditions such as the release of political prisoners, the democratization of the country and a rollback in the agreements signed by Obama. He even signed a presidential proclamation in front of the gaudy auditorium and took out with a flourish the Sharpie pen before the uproar of those who were closest.

The compliance of that plan began with the creation of a group of advisors, but it moved very slowly. It started with Cuban-American Senator Marco Rubio, it was extended to National Security Advisor John Bolton, who was joined by the special presidential adviser, also a Cuban-American, Mauricio Claver-Carone. But the first two years were very slow. No significant changes came from the White House. Some in Miami began to despair.

When everything started changing

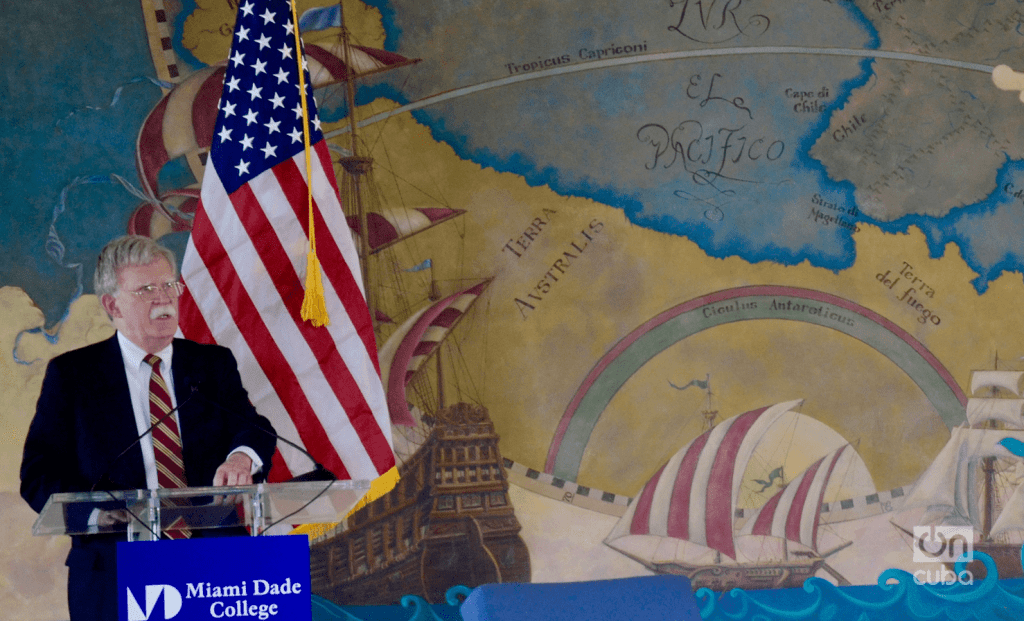

In November 2018 the first serious actions occur. It all starts when Bolton travels to Miami to explain the president’s Latin American policy. He began by defining that for Trump, Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua were the “tyrannical troika,” he affirmed that hardline policies against the three countries were approaching, but made the attendees’ mouth water because he didn’t give more details. He only said that the administration was carefully considering reactivating Title III of the Helms-Burton Act, but that there was still no consensus, so “we must still study the matter further to know what to do.”

Similarly, when they suggested to him that the United States should “immediately” prosecute the first secretary of the Cuban Communist Party, General Raúl Castro, for the downing of the Brothers to the Rescue light aircraft in 1996, which led to the promulgation of the Helms-Burton Act by former President Bill Clinton, Bolton also evaded the issue and left others disappointed: “We better leave it for when Cuba is a democratic country,” he said. And he returned to Washington.

2019

In April of this year, coinciding with the anniversary of the Bay of Pigs invasion, a curiously failed initiative by Washington, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo gave a press conference and announced the full application of the Helms-Burton Act, which allows Americans and naturalized Cubans to sue foreign companies operating in Cuba.

And thus begins the entire roll back. The administration initiates an almost total dismantling offensive of what had been achieved during Barack Obama’s thaw. It involved a series of sanctions with almost immediate impact on the life of the island, especially the incipient private sector, which is deprived of its main foreign customers from the cruises to the island, restrictions on direct flights from the United States, which caused a serious reduction in the customers of private restaurants, rental of apartments and private rooms, taxi service and the private souvenir industry, tourist guides and a range of professions that had emerged around tourism.

In national terms, the intensification of sanctions on government companies, mainly those under military administration, was almost the absolute disaster. Former Cuban diplomat, Carlos Alzugaray, said to OnCuba that if the previous two years were bad, 2019 has been the worst.

“Since Trump took office, every year has been worse due to his government’s unilateral actions. The president’s entire policy has been a kind of emulation with his predecessors, whose goal was a regime change in Cuba using coercive methods. The interesting and paradoxical thing is that all kinds of sanctions that make up the blockade have been paradoxically intensified after diplomatic relations had been reestablished under Obama and the start of a normalization process,” he said.

In his opinion, it seems that President Trump “is engaged in reversing everything and rolling it back to the years 1961-1977, in which there were no relations and in which even people-to-town contacts were non-existent,” the former diplomat added, for whom there is no reason for “this intensification, as it existed during the Cold War years.”

A fact of this current confrontation is the role of the U.S. press, which has disregarded the issue and has engaged in “fake news campaigns around Cuba’s role in Venezuela and its health cooperation policy.” In addition, Trump’s policy change is due to “domestic considerations, such as favoring a sector of the Florida electorate in favor of a hardline against Cuba or the regional one such as the situation in Venezuela and South America,” underlined Alzugaray.

However, the intensification of economic and social restrictions doesn’t seem to lead to a total cut in relations. “Signals have been received from both parties that they are not interested in a total break, which suggests that, if there is a change of government in the United States in 2020, they can be recovered in a relatively short period,” said the former Cuban diplomat, for whom if there was something positive in this whole process it was “the intelligence of Cuban diplomacy in not being provoked, even in spite of the very aggressive actions of the U.S. Embassy in Havana, on which I can only say there’s nothing diplomatic about them.”

The last cruise ship with U.S. passengers that was allowed to travel to Cuba left Havana on Wednesday and arrived in Miami on Thursday. Some travelers shared their opinions with OnCuba about the recent ban on cruise trips to the island.

Posted by OnCuba on Thursday, June 6, 2019

For Cuban academic Rafael Hernández, the deterioration has other aspects that are “less bad.”

“The ‘worst’ thing about the U.S. policy towards Cuba has been the virtual suspension of the orderly migration flow (agreed since 1995-96), with the closing of the consular office in Havana under the pretext of the sonic attacks, a situation completely determined by the U.S. side that illustrates the counterproductive effect, more than on the island’s government, on all Cubans, here and there,” the director of the magazine Temas said to OnCuba.

Another aspect that is “worse” is “the use of fear, and its impact on visits and contact between the two societies. Along with the cancellation of people-to-people travel licenses and the end of cruises, the straining of visits to Cuba, and in particular the impact on academic and cultural exchanges, built against all odds for more than three decades, have been damaged like never before. Despite maintaining institutions’ interest on both sides, and not having canceled the general license for these exchanges, the ‘safety warnings’ issued by the United States government on visits to Cuba have had an inhibitory effect,” he said.

A difficulty, however, that has highlighted the strong motivation of academics and artists, churches, businesspeople, airlines, scientists, etc. of overcoming restrictions on freedom of information and the blockade, and that has caused a rejection “among Cubans from here and there who don’t resign themselves to isolation,” said Hernández.

The academic is in favor of seeing the bilateral crises in terms of “half-full glasses,” so “I’m not going to refer to the well-known list of damages (or setbacks) inflicted on Cuba through harassment and sanctions,” but rather “the list of ‘what could have been, which is significantly long.”

Thus, “cooperation between coast guard services in matters of migration and drug trafficking was not suspended, nor were the twelve categories that allow visiting the island canceled (only the people-to-people one), nor was the service suspended of the 14 airlines that travel (they were restricted to Havana, but continued to several cities in the United States), nor was Cuba placed on the list of terrorist countries, nor were the licenses granted to the Rockwell Institute and the Starwood hotel chain closed, nor was the Airbnb activity in Cuba made illegal, nor were the permits to Google and other communication companies, nor academic and artistic relations prohibited.”

This, in his opinion, shows that “beyond ideological differences, we have common interests, proof found in the continued visits to the island and remittances, and demonstrates that none of these restrictive policies respond to a Cuban policy, nor to the myth that emigrants vote with their feet when they leave the island. Above all, the bridge between Cuban society and its emigration is reaffirmed,” he said, although the United States closed its Consulate in Havana and greatly affected Cubans’ trips to their neighbor to the north.

Even so, the two analysts agree that, as Hernández said, “the balance of 2018-2019 is negative in absolute terms, and has been entirely the work of the United States.”

Cuban-American professor Carlos Lazo compiled the testimonies of several Cubans whose businesses have been affected after the restrictive measures of trips to #Cuba, recently taken by the government of Donald Trump.

Posted by OnCuba on Wednesday, July 17, 2019

Chronology

April 17: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announces that President Trump would not suspend Title III of the Cuban Freedom and Democratic Solidarity Act, better known as the Helms-Burton Act, for no additional period of time. This title allows U.S. citizens whose properties were nationalized in the 1960s to sue in court any person, regardless of their nationality, who knowingly and intentionally “traffic” with those properties, and includes those interested Cuban citizens who were nationalized Americans after the expropriations of the 1960s.

May 2: The Trump administration’s national security adviser, John Bolton, declares that Cuba has 20,000 soldiers in Venezuela and was intervening in its internal affairs. Does not present proof.

May 3: The Trump administration activates Title III of the Helms Burton Act. As of 1996, when it was signed by Bill Clinton, the successive administrations had postponed its application every six months after an agreement with several trade partners with investments on the island, in particular the European Union and Canada.

May 12: Senators Marco Rubio and Bob Menéndez present a bill to prohibit the official recognition of Cuban trademark rights in the United States.

June 5: The Treasury Department announces the policy of not allowing people-to-people cultural and educational trips to Cuba, and other measures related to travel and transportation services, remittances, banking, commerce and telecommunications businesses. “These actions will help keep U.S. dollars out of the reach of Cuban military and intelligence and security services,” said Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

June 5: The last U.S. cruise ship departs from Havana, thus putting an end to a brief boom. Seventeen companies and 27 ships had gotten to operate. According to John Kavulich, president of the U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, the cruises contributed between 63 million to 107 million dollars to the Cuban government, a tiny part of the 2.5 billion dollars in revenue reported by the Ministry of Tourism that year.

September 6: The Treasury Department modifies the Cuban Assets Control Regulations to impose new sanctions on Cuba. “Through these regulatory amendments, the Treasury is denying Cuba’s access to foreign currencies and we are curbing the bad behavior of the Cuban government while continuing to support the people of Cuba who suffer so much,” said Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

The new sanctions increase the restrictions for sending remittances and bank transactions. The United States imposes a limit of 1,000 dollars per quarter for the sending of family remittances. It also prohibits sending remittances to close relatives of Cuban officials and members of the Communist Party.

It also imposes restrictions on U-turn transactions, which consist of transfers of funds carried out through a U.S. bank, but which do not originate or have as destination that country, and in which neither the issuer nor the recipient are subject to U.S. jurisdiction. With the new regulation, the White House puts an end to a prior permit authorizing these movements.

October 25: The U.S. government announces that it will suspend commercial airline flights to the interior of the island. As of December 10, they will only be allowed to land in Havana. This means the suspension of flights to another 10 airports throughout the island. The ban on flights to other cities in Cuba does not apply to charter flights.

November 15: Coinciding with the celebration of Havana’s 500th anniversary, the U.S. government adds five hotels to its list of enterprises with which Americans are prohibited from negotiating. In a press release issued the day before that anniversary, the State Department reports that these changes will take effect on November 19.

November 27: The new restrictions on travel to Cuba imposed by the United States had a negative impact on the tourism sector of the Caribbean country. In September 2018, 51,776 Americans traveled to Cuba, in the same month in 2019 only 13,094 did so, for a decrease of 74.7%.

From January to September of this year, U.S. visitors decreased by 5.2%, from 460,288 to 436,453.

December 10: The measure on commercial flights announced on October 25 takes effect.

December 16: Carlos Fernández de Cossío, director of the United States Department of the Cuban Foreign Ministry, said in Havana that: “Cuba wants normal relations with the U.S., but Havana won’t lose any sleep if the administration of President Donald Trump breaks official ties between the two countries.”

Epilogue

In the first days of January, Trump is coming to Miami to give a speech that will undoubtedly address relations with the island and Venezuela. It will be time to see if the 2019 annus horribilis will continue in this new decade.